Sipa USA via AP

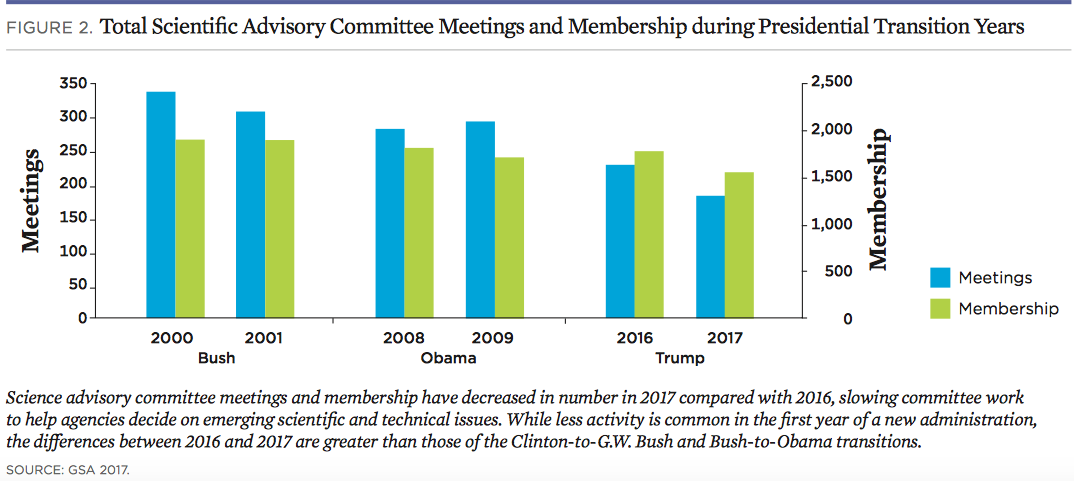

Once more, the Trump administration has upset the norms. For decades, scientists have provided expert advice to the White House and federal agencies, helping inform decisions that affect the nation’s health and safety. But, according to a report from the Union of Concerned Scientists released last week, the Trump administration has neglected, suspended, or disbanded many science advisory committees.

Their members have been “serving science and serving their country,” said former New Jersey congressman Rush Holt, who is now the CEO of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. “This recent report puts numbers to what I expected; that the advisory committees are not being well used—it’s troubling.”

The analysis examined 73 committees designated as “scientific and technical” across two dozen departments, agencies, and sub-agencies. While agency advising committees varied, and some were still quite active, the report found “an aggregate pattern of failure to adhere to committees’ chartered missions.” The Department of Energy, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Department of the Interior met less frequently in 2017 than at any time since the government began tracking this data in 1997. The DOE, the EPA, and the Department of Commerce advisory committees also have fewer experts serving as members than at any point in the last two decades.

“They are mostly science and technical experts focusing on emerging issues, and they are really drilling down on the science,” said the report’s coauthor Genna Reed, a science and policy analyst in the Center for Science and Democracy at the Union of Concerned Scientists. She emphasizes that advisory committees are not political. “The fact that they are now becoming political is telling, and especially frustrating for the individuals who want to be doing the work that they are charged with doing.”

The pattern of marginalizing science advice starts with the president, the report says. Unlike any of his predecessors in the past four decades, Trump still hasn’t named a presidential science adviser who would oversee the now largely dormant Office of Science and Technology Policy. By the end of last year, Trump had filled only 20 of the 83 government posts that the National Academies of Science designates as “scientist appointees”; at the same point in their administrations, President Barack Obama had filled 63 of those positions and President George W. Bush had filled 51.

The role of federal advisory committees is to ensure that “federal officials and the nation have access to information and advice on a broad range of issues affecting federal policies and programs” according to the General Services Administration, the independent government agency that helps manage these committees. Over the years, these groups have weighed in on issues ranging from infectious diseases to environmental pollution. Holt points out that without their expert advice, an evidence-based scientific perspective “just isn’t represented in policy making.”

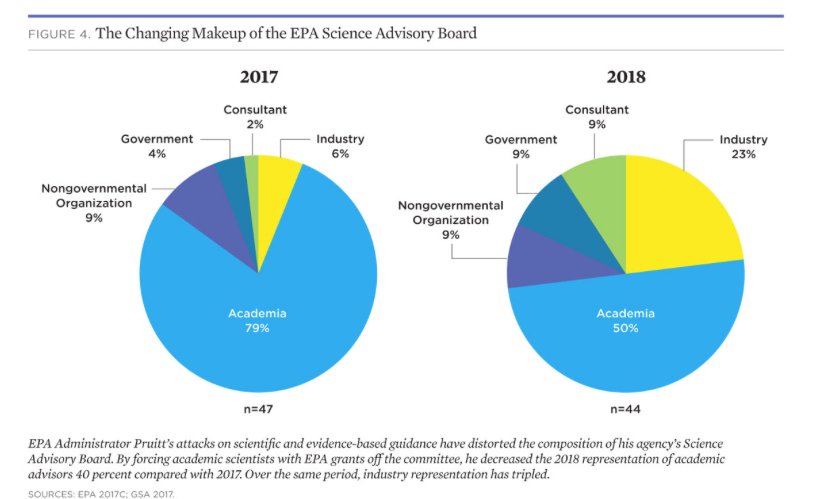

At the EPA, Administrator Scott Pruitt aggressively realigned flagship science boards advising the agency, including the Science Advisory Board and the Board of Scientific Counselors. The Trump administration has also proposed slashing funding for the Science Advisory Board by 84 percent, hindering the work of the 47-member board.

Pruitt began his sweep of the boards by breaking with tradition and opting not to renew the appointments of Scientific Counselors whose terms were ending. In May, Robert Richardson, an ecological economist and professor at Michigan State University who for three years served on the BOSC, learned his term would not be renewed. By the end of the following month, 38 of the 49 sub-committee members had been given the same message.

Today, I was Trumped. I have had the pleasure of serving on the EPA Board of Scientific Counselors, and my appointment was terminated today.

— Robert Richardson (@ecotrope) May 5, 2017

The EPA’s decision not to renew membership was “inflammatory,” Richardson said in an email: “The decisions to dramatically reshape and revamp these boards sends a message that the administration does not value the scientific expertise, experience, and level of trust that are associated with members whose terms are not renewed.” Ryan Jackson, Pruitt’s chief of staff, told the Washington Post that board members whose terms are not being renewed could reapply for their positions.

In the past, some expert advisers on EPA boards and committees would also receive grants from the EPA to continue their research. In October, Pruitt put an end to this by mandating that EPA grant recipients were no longer eligible to serve on advisory committees. Instead, membership on these committees reflects increased representation of industry interests, the UCS report found. “In effect, people who have studied the issues the most and have been closest to the issues are not eligible to provide advice,” Holt, the CEO of AAAS, said.

Charles Werth, a professor of environmental health engineering at the University of Texas, Austin, was not appointed to a second term on the EPA Science Advisory Board. He had previously served alongside representatives with industry backgrounds who “all seemed to be honest and diligent.” Nonetheless, he adds, “There is the perception and the risk that instead of providing the best scientific advice, they will provide advice that benefits their industry.”

EPA spokesman Jahan Wilcox said in an email that with the change in administration and “many new priorities for the Agency,” time is needed to “identify and prepare for scientific review.” The agency expects to fully use its advisory committees “to ensure the highest quality independent advice to provide a foundation for the Agency’s policies and decisions,” he wrote.

At the Department of Energy, some 44 percent of science advisory committees failed to hold the number of meetings dictated by their charters last year. The Secretary of Energy Advisory Board, which has has been used extensively by all but one DOE secretary for nearly three decades, has been dormant under the current administration. At the start of the new administration, all but one of the 19 board members offered their resignations, as is customary, and said they never received a reply, according to the UCS report. At a DOE hearing on January 10, Energy Deputy Secretary Dan Brouillette said the board “hasn’t been disbanded” and the secretary is “still in the process of evaluating membership on that board.”

Dan Reicher, executive director of the Steyer-Taylor Center for Energy Policy and Finance at Stanford University, said he was less concerned about not receiving a response to his resignation letter, than he was about the fact that the board has not been reestablished. He was a staff member of President Carter’s Commission on the Accident at Three Mile Island, served as an assistant secretary of energy during the Clinton administration, and as a member of President Obama’s Transition Team. He said the board “gives the Secretary the ability to dig into key issues and opportunities and hear a variety of perspectives from people who are somewhat independent of the agency, but who as members are committed to providing good advice.”

In May, the Department of the Interior announced a formal review of more than 200 of its advisory panels, and meetings through September were postponed. In January, nearly all members of a National Park Service advisory board, which was not included in the report, resigned in protest after Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke failed to meet with them or hold any meetings last year. Former Alaska governor and advisory board chairman Tony Knowles told High Country News:

“When you’re on permanent hold, at some time you’ve gotta hang up. There’s no one to talk to but yourselves. By nine of us resigning, we felt we’d be able to get the microphone briefly to at least talk to the American people about climate change, about preserving the natural diversity of wildlife, about making sure underrepresented minorities not only come to the parks but are employees there.”

Another notable committee that received the axe last year was Interior’s Advisory Committee on Climate Change and Natural Resource Science, which had advised the secretary on the managing natural resources in the face of global warming. Conservation biologist Paul Beier, a professor at Northern Arizona University and a former member of that committee, said they used to meet about four times a year. The government had already paid for his ticket to an April meeting when he learned that the meeting was canceled. “The next thing I got was a letter that said thank for your service,” Beier said. “The letter didn’t say, ‘By the way you are never going to meet again.’”

The report details the disbanding of the Food Advisory Committee, a longstanding committee at Food and Drug Administration weighing in on food science, safety and nutrition. It also includes information on a reported “word ban” at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the disbanding of the Advisory Committee for the Sustained National Climate Assessment in the Department of Commerce.

The Union of Concerned Scientists’ report recommends that current and former science advisors speak out when the government sidelines scientific work and findings, and asked Congress to hold hearings on the status of various committees. The group called for the Government Accountability Office to assess whether agencies are following the 1972 Federal Advisory Committee Act that mandates how the committees operate, saying they must be “fairly balanced in terms of the points of view represented,” and recommended that agencies take steps to ensure advice will not be “inappropriately influenced by the appointing authority or by any special interest.”

Reed said while the sidelining of science advisory boards is disheartening, she is encouraged that scientists and other experts are still willing to offer their time and expertise. “They really want to help inform our policymakers and make sure they are aware of the research coming out on an issue,” Reed said. “All we need is the administration to at some point realize they need to value this science advice that is built into our government system.”

Conservation biologist Beier is not optimistic that will happen. “This is exactly what I expect from this president who clearly doesn’t give a flip about truth and science,” he said.