Mother Jones illustration; nechaev-kon/Getty

This story was originally published by the Center for Public Integrity. It appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Maine’s invasion came early this year. In recent hotbeds of tick activity—from Scarborough to Belfast and Brewer—people say they spotted the eight-legged arachnid before spring. They noticed the ticks—which look like moving poppy seeds—encroaching on roads, beaches, playgrounds, cemeteries, and library floors. They saw them clinging to dogs, birds, and squirrels.

By May, people were finding the ticks crawling on their legs, backs and necks. Now, in midsummer, daily encounters seem almost impossible to avoid.

Maine is home to 15 tick species but only one public-health menace: the blacklegged tick—called the “deer” tick—a carrier of Lyme and other debilitating diseases. For 30 years, an army of deer ticks has advanced from the state’s southwest corner some 350 miles to the Canadian border, infesting towns such as Houlton, Limestone, and Presque Isle.

“It’s horrifying,” says Dora Mills, director of the Center for Excellence in Health Innovation at the University of New England in Portland. Mills, 58, says she never saw deer ticks in her native state until 2000.

The ticks have brought a surge of Lyme disease in Maine over two decades, boosting reported cases from 71 in 2000 to 1,487 in 2016—a 20-fold increase, the latest federal data show. Today, Maine leads the nation in Lyme incidence, topping hot spots like Connecticut, New Jersey, and Wisconsin. Deer-tick illnesses such as anaplasmosis and babesiosis—a bacterial infection and a parasitic disease similar to malaria, respectively—are following a similar trajectory.

The explosion of disease correlates with a warming climate in Maine where, over the past three decades, summers generally have grown hotter and longer and winters milder and shorter.

It’s one strand in an ominous tapestry: Across the United States, tick- and mosquito-borne diseases, some potentially lethal, are emerging in places and volumes not previously seen. Climate change almost certainly is to blame, according to a 2016 report by 13 federal agencies that warned of intensifying heat, storms, air pollution and infectious diseases. Last year, a coalition of 24 academic and government groups tried to track climate-related health hazards worldwide. It found them “far worse than previously understood,” jeopardizing half a century of public-health gains.

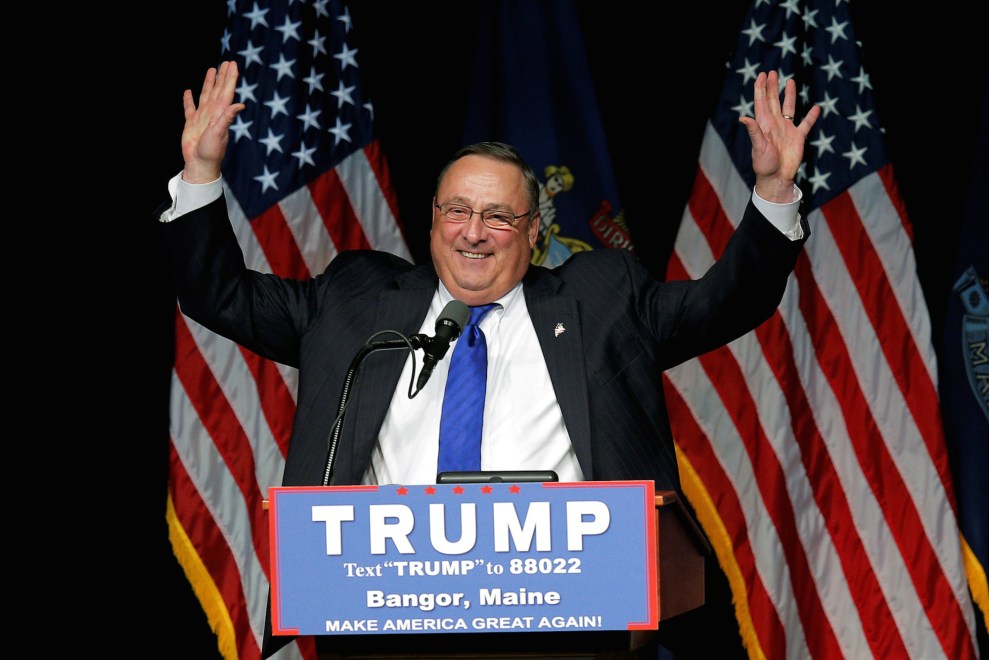

Yet in Maine, Gov. Paul LePage—a conservative Republican who has questioned global-warming science—won’t acknowledge the phenomenon. His administration has suppressed state plans and vetoed legislation aimed at limiting the damage, former government officials say. They say state employees, including at the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention, have been told not to discuss climate change.

“It appears the problem has been swept under the rug,” says Mills, who headed the Maine CDC from 1996 to 2011. In the 2000s, she sat on a government task force charged with developing plans to respond to climate change; those efforts evidently went for naught. “We all know this response of ignoring it and hoping it goes away,” she says. “But it never goes away.”

In an emailed statement, LePage’s office denied that the governor has ignored climate change. It cited his creation of a voluntary, interagency work group on climate adaptation in 2013, which includes the Maine CDC. “To assume…that the governor has issued a blanket ban on doing anything related to climate change is erroneous,” the statement said. A recent inventory of state climate activities performed by the group, however, shows that most of the health department’s work originated with the previous administration.

Climate’s role in intensifying diseases carried by “vectors”—organisms transmitting pathogens and parasites—isn’t as obvious as in heat-related conditions or pollen allergies. But it poses a grave threat. Of all infectious diseases, those caused by bites from ticks, mosquitoes and other cold-blooded insects are most climate-sensitive, scientists say. Even slight shifts in temperatures can alter their distribution patterns.

In May, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported a tripling of the number of disease cases resulting from mosquito, tick and flea bites nationally over 13 years—from 27,388 cases in 2004 to 96,075 in 2016. Cases of tick-related illnesses doubled in this period, accounting for 77 percent of all vector-borne diseases. CDC officials, not mentioning the words “climate change,” attributed this spike partly to rising temperatures.

Heedless officials like LePage are one reason the government response to the human impacts of climate change has been so sluggish. But discord within the health community has stymied action, too, according to interviews with more than 50 public-health experts and advocates, and a review of dozens of scientific studies and government reports. State and local health department employees may believe climate change is happening but don’t necessarily see it as a public-health crisis, surveys show. Many find it too taxing or nebulous a problem to tackle.

“Like most health departments, we are underfunded and our list of responsibilities grows each year,” wrote one investigator from Arizona, echoing the 23 professionals who responded to a Center for Public Integrity online questionnaire.

The fraught politics of climate change also loom large. Chelsea Gridley-Smith, of the National Association of City and County Health Officials, says many local health departments face political pressures. Some encounter official or perceived bans on the term “climate change.” Others struggle to convey the urgency of threats when their peers don’t recognize a crisis.

“It’s disheartening for folks who work in climate and health,” says Gridley-Smith, whose group represents nearly 3,000 departments. “When politics come into play they feel beat down a little.”

This reality is striking in Maine, among 16 states and two cities receiving a federal grant meant to bolster health departments’ responses to climate-related risks. Under the program—known as Building Resilience Against Climate Effects, or BRACE—federal CDC employees help their state and local counterparts use climate data and modeling research to identify health hazards and create prevention strategies. National leaders have praised the Maine CDC’s BRACE work, which includes Lyme disease.

But the Maine CDC employees declined requests to interview key employees and didn’t respond to written questions. Instead, in a brief email, a spokeswoman sent a description of initiatives meant to help people avoid tick bites and Lyme disease. Sources close to the agency say the LePage administration is concerned about tick-related illnesses but not their connection to climate. In its statement the governor’s office said this relationship “is of secondary concern to the immediate health needs of the people of Maine.”

The ticks, meanwhile, continue their northerly creep. In Penobscot County—where the Lyme incidence rate is eight times what it was in 2010—the surge has unnerved residents. Regina Leonard, 39, a lifelong Mainer who lives seven miles north of Bangor, doesn’t know what to believe about climate change. But she says the deer tick seems “rampant.”

In 2016, her son Cooper, then 7, tested positive for Lyme disease after developing what she now identifies as an expanding or “disseminated” rash, a classic symptom. Red blotches appeared on his cheeks, as if he were sunburned. The blotches coincided with other ailments—malaise, nausea. Weeks later, they circled his eyes. The ring-shaped rash spread from his face to his back, stomach and wrists.

Leonard says Cooper could barely walk during his 21-day regimen of antibiotics. His fingers curled under his hands. He stuttered. The thought of being bitten by another tick terrifies him to this day.

“At this rate,” Leonard says, “we’re all going to end up with Lyme.”

Cooper Leonard tested positive for Lyme disease in 2016 after developing an expanding rash. Within hours, the ring-shaped rash spread from his face to his back, stomach and wrists.

The spread of Lyme disease has followed that of deer ticks. The incidence of Lyme has more than doubled over the past two decades. In 2016, federal health officials reported 36,429 new cases, and the illness has reached far beyond endemic areas in the Northeast to points west, south and north.

The official count, driven by laboratory tests, underplays the public-health problem, experts say. In some states, Lyme has become so prevalent that health departments no longer require blood tests to confirm early diagnosis. The testing process—which measures an immune response against the Lyme-causing bacteria—has limitations as well. It misses patients who don’t have such a reaction. Those who show symptoms associated with a later stage—neurological issues, arthritis—can face inaccurate results. The CDC estimates the actual caseload could be 10 times higher than reported.

Dr. Saul Hymes heads a pediatric tick-borne disease center at Stony Brook University on Long Island, a Lyme epicenter since the disease’s discovery in 1975. He’s noticed a change: Patients file into his office as early as March and as late as November. Often, they appear in winter. Deer-tick samples collected from 2006 to 2011 at the university’s Lyme lab show a jump in tick activity in December and January.

States where Lyme hardly existed 20 years ago are experiencing dramatic changes. In Minnesota, deer ticks and the illnesses they cause appeared in a few southeastern counties in the 1990s. But the tick has spread northward, bringing disease-causing bacteria with it. Now, in newly infested areas, says David Neitzel, of the Minnesota Department of Health’s vector-borne disease unit, “We haven’t been able to find any clean ticks. They’re all infected.” Minnesota ranks among the nation’s top five states for Lyme cases; it places even higher in incidence of anaplasmosis and babesiosis.

A similar transformation is under way in Maine, where the 2017 count of 1,769 Lyme cases represented a 19-percent increase over the previous year. Anaplasmosis cases soared 78 percent during that period, babesiosis 42 percent.

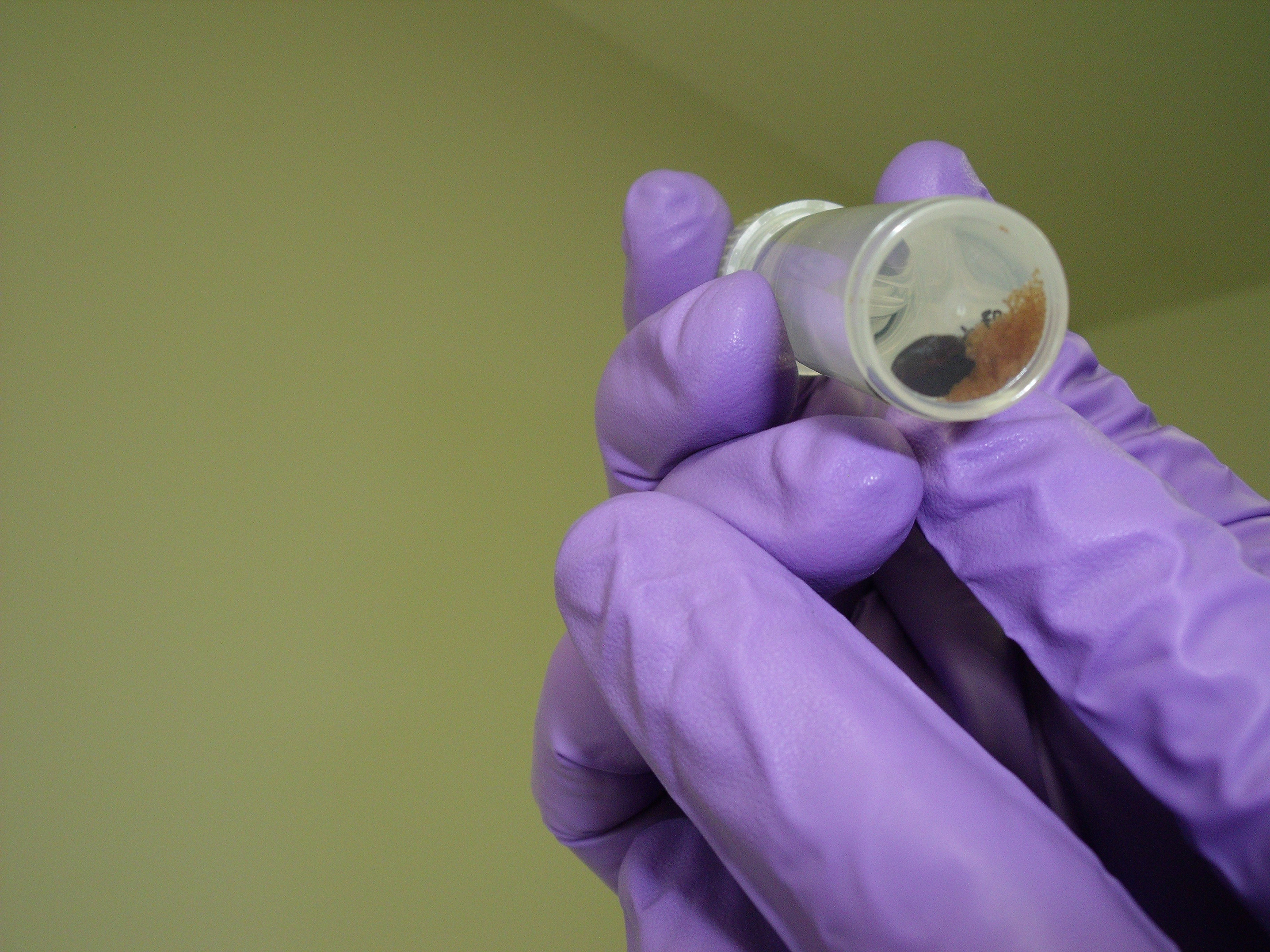

“It’s quite a remarkable change in a relatively short period,” says Dr. Robert Smith, director of infectious diseases at Maine Medical Center in Portland. Researchers at the hospital’s vector-borne disease laboratory have tracked the deer tick’s march across all 16 of Maine’s counties since 1988. Through testing, they’ve identified five of the seven pathogens carried by deer ticks. That’s five new maladies, some life-threatening.

Betsy Garrold, 63, lives on 50 acres amid dairy farms in Knox, a rustic town of 900 in Waldo County, where the Lyme incidence is three times the state average. A retired nurse midwife, Garrold says she long viewed the disease as many in the health profession would: mostly benign when treated with antibiotics. In 2013 she tested positive for Lyme after a red, brick-shaped rash covered her stomach and legs. She lost her ability to read and write and struggled to form a simple sentence.

“It was the worst experience of my life,” says Garrold, who previously had weathered bouts of tropical intestinal diseases.

Lisa Jordan, a patient advocate who lives in Brewer, just southeast of Bangor, says she’s already inundated with phone calls from people stricken by Lyme. On her cul-de-sac, she counts 15 out of 20 households touched by the disease. Three of her family members, herself included, are among them. “It’s a huge epidemic,” she says.

The link between Lyme disease and climate change isn’t as direct as with other vector-borne diseases. Unlike mosquitoes, which live for a season and fly everywhere, deer ticks have a two-year life cycle and rely on animals for transport. That makes their hosts key drivers of disease. Young ticks feed on mice, squirrels, and birds, yet adults need deer—some suggest 12 per square mile—to sustain a population.

Rebecca Eisen, a federal CDC biologist who has studied climate’s influence on Lyme, notes that deer ticks dominated the East Coast until the 1800s, when forests gave way to fields. The transition nearly wiped out the tick, which thrives in the leaf litter of oaks and maples. The spread of the deer tick since federal Lyme data collection began in the 1990s can be traced to a decline in agriculture that has brought back forests while suburbia has sprawled to the woods’ edges, creating the perfect habitat for tick hosts.

Betsy Garrold lives on 50 acres in Waldo County, Maine, where the Lyme incidence rate is three times the state average.

Eisen suspects this changing land-use pattern is behind Lyme’s spread in mid-Atlantic states like Pennsylvania, where the incidence rate has more than tripled since 2010. “It hasn’t gotten much warmer there,” she says.

But climate is playing a role. Ben Beard, deputy director of the federal CDC’s climate and health program, says warming is the prime culprit in Lyme’s movement north. The CDC’s research suggests the deer tick, sensitive to temperature and humidity, is moving farther into arctic latitudes as warm months grow hotter and longer. Rising temperatures affect tick activity, pushing the Lyme season beyond its summer onset.

Canada epitomizes these changes. Over the past 20 years, Dr. Nicholas Ogden, a senior scientist at the country’s Public Health Agency, has watched the tick population in Canada spread from two isolated pockets near the north shore of Lake Erie into Nova Scotia, Quebec, and Ontario, the front lines of what he calls “a vector-borne disease emergency.”

Scientists say ticks can use snow as a blanket to survive cold temperatures, but long winters will limit the deer tick, preventing it from feeding on hosts and developing into adults. In the 2000s, Ogden and colleagues calculated a threshold temperature at which it could withstand Canada’s winter. They surmised that every day above freezing—measured in “degree days,” a tally of cumulative heat—would speed up its life cycle, allowing it to reproduce and survive. They mapped their theory: As temperatures rose, deer ticks moved in.

By 2014, the researchers had published a study examining projected climate change and tick reproduction. It shows higher temperatures correlating with higher tick breeding as much as five times in Canada and two times in the northern United States; in both places, the study shows, a Lyme invasion has followed.

The Canadian health agency reports a seven-fold spike in Lyme cases since 2009. “We know it’s associated with a warming climate,” Ogden says.

The US Environmental Protection Agency concluded as much in 2014, when it named Lyme disease an official “indicator” of climate change—one of two vector infections to receive the distinction. In its description, the EPA singles out the caseloads of four northern states, including Maine, where Lyme has become most common.

Maine researchers have found a strong correlation between tick activity and milder winters. According to their projections, warming in Maine’s six northernmost counties—which collectively could gain up to 650 more days above freezing each year by 2050—will make them just as hospitable to deer ticks as the rest of the state.

Research like this is crucial, experts say. Yet the federal government has failed to prioritize it. From 2012 to 2016, the National Institutes of Health spent a combined $32 million on its principal program on climate change—0.1 percent of its $128 billion budget, says Kristie Ebi, a University of Washington public health professor. NIH spending has gone up in the past two fiscal years, to an average of $193 million annually. But that’s still less than the $200 million Ebi says health officials need annually to create programs that will protect Americans. And NIH spent 38 times as much on cancer research during the two-year period.

Congress has done little to fix the problem. Last year, US Rep. Matt Cartwright, a Democrat from Pennsylvania, sponsored legislation calling for an increase in federal funding for climate and health research and mandating the development of a national plan that would help state and local health departments. The bill, sponsored by 39 House Democrats, is languishing in committee. Sources on Capitol Hill say it has no chance of advancing as long as climate-denying Republicans hold a majority.

The only federal support for state and city health officials on climate change is the CDC’s BRACE grant program. George Luber, chief of the CDC’s climate and health program, considers it “cutting-edge thinking for public health.” He intends to expand it to all 50 states, but funding constraints have kept him from doing so.

Republicans in Congress have tried repeatedly to excise BRACE’s $10 million budget, to no avail. Its average annual award for health departments has remained around $200,000 for nearly a decade.

The modest federal response has shifted the burden to state and local health departments, most of which have “limited awareness of climate change as a public health issue,” according to a 2014 Government Accountability Office report. Of the two dozen responding to the Center’s questionnaire, only one said her agency had trained staff on climate-related risks and drafted an adaptation plan.

By contrast, BRACE states are hailed as national models for climate-health adaptation. In Minnesota, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont—where deer ticks and their diseases are moving north—health officials have modeled future climate change and begun education campaigns in areas where Lyme is expected to rise.

Dora Mills, the former Maine CDC chief, oversaw the department’s bid for a BRACE grant in 2010. State epidemiologists already were surveying tick-related illnesses, but no one was asking why deer ticks were spreading or which areas were in jeopardy.

One year later, the department launched a program prioritizing vector-borne disease and extreme heat. Some employees worked with experts to model high-heat days and analyze their relationship with heat-induced hospital visits, among other activities. Much of the funding went to climate scientists and vector ecologists, who looked at the relationship between deer ticks and warming temperatures and did a similar study involving mosquitoes. They planned to develop a broader tick model that would examine the climate and ecological processes underlying the spread of Lyme disease in Maine and project its future burden.

By 2013, the administration of Gov. LePage, elected in 2010 as a denier of what he called “the Al Gore science” on climate change, was clamping down. Norman Anderson worked at the Maine CDC for five years and managed its climate and health program. He recalls department public relations officials warning him not to talk about his work and refusing to greenlight his appearances.

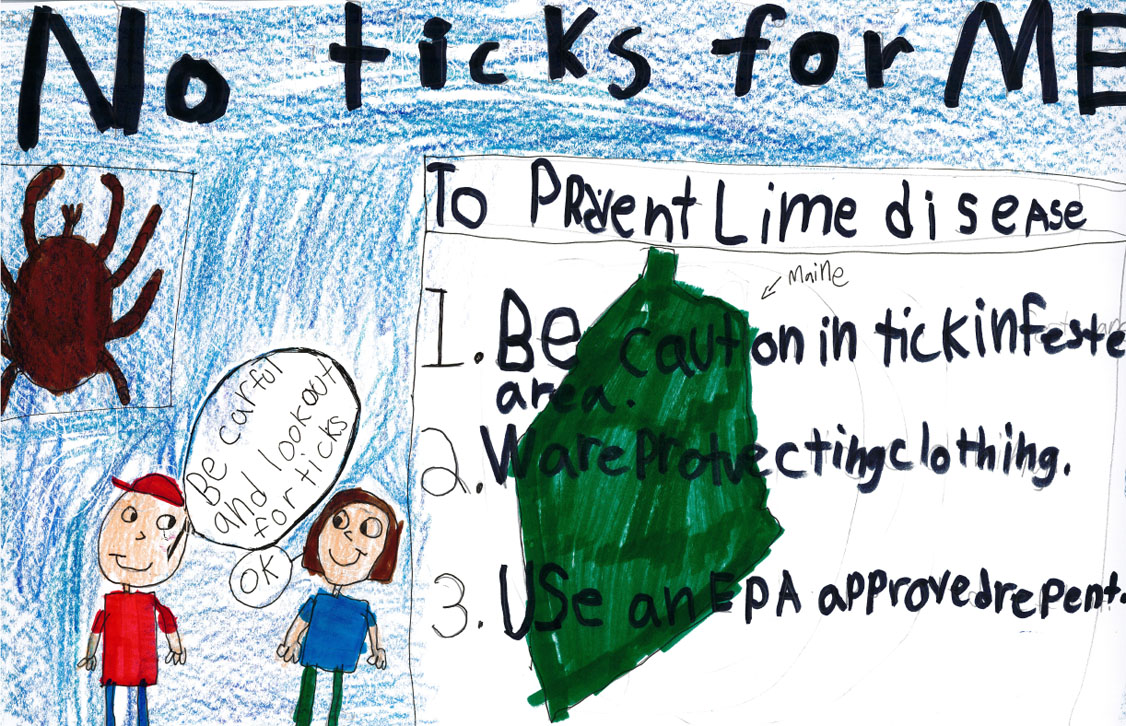

Eventually the governor eliminated the department’s climate-change research. Scientists say they had to replace their ambitious modeling plan with rudimentary activities and spend their remaining BRACE funds on “tick kits”—complete with beakers of deer ticks in nymph and adult stages—to distribute to school children.

Today, the Maine Center for Disease Control’s climate and health program amounts to little more than a half-dozen initiatives on ticks and tick-borne diseases.

“Governor LePage said, ‘No one is doing climate-change research,'” says Susan Elias, a vector ecologist at the University of Maine’s Climate Change Institute who worked on the tick-climate research and is developing the broader model for her Ph.D. dissertation. “That message came down from on high through official state channels.”

LePage’s office defended the governor’s decision, arguing that scientists studying the relationship between climate and disease “are best funded in research settings such as large universities,” not the Maine CDC.

LePage did approve a proposal by the Maine CDC to renew its BRACE grant, but only after narrowing the scope. Employees had to abandon planned climate research related to the health impacts of extreme weather and worsening pollen, records show. Their heat research yielded results—indeed, the threshold at which officials issue dangerous heat advisories was lowered from 105 to 95 degrees Fahrenheit after their analysis had found it didn’t protect Mainers’ health. But employees had to scrap their heat-response plans nonetheless. The only BRACE work that LePage approved involved Lyme prevention.

In 2014, Anderson, frustrated by what he calls the “repressive” environment, quit the Maine CDC. The department’s larger “strategy around climate and health had just been whittled away,” he says.

Today, the Maine CDC’s climate and health program amounts to little more than a half-dozen initiatives on ticks and tick-borne diseases. Health officials have developed voluntary school curricula and online campaigns targeting the elderly, for instance. They’ve launched training videos for school nurses and librarians.

The department’s “main prevention message is encouraging Maine residents and visitors to use personal protective measures to prevent tick exposures,” it said in a 2018 report.

That report, filed by the Maine CDC with state legislators, hints at the department’s myopic focus on the accelerating public-health problem. Its vector-borne disease work group, consisting of scientists, pest-control operators and patient advocates, has extensive knowledge on ticks and tick-borne diseases, yet has no mandate to draft a statewide response plan, members say. Its published materials make no mention of Lyme’s connection to climate change.

Sources close to the Maine CDC say the prevention work is the best it can do with limited resources. At $215,000 a year, the BRACE grant—which totals $1.1 million over five years—isn’t enough to cover a 38,385-square-mile state with 1.3 million residents, they say. No state money is directed toward the surge in tick-related illnesses.

LePage’s office cites the governor’s leadership in building an $8 million research facility at the University of Maine, which opened last month. The laboratory—the product of a ballot initiative in 2014—houses the university’s tick-identification program. Director Griffin Dill considers it a major upgrade from the converted office in which he logged tick samples for five years. It will enable him to expand tick surveillance and test ticks for pathogens. Still, he’s candid about the bigger picture.

“We’re still so inundated with tick-borne disease,” Dill says. “We’re trying to plug holes in the dam.”

Tick ecologists like Griffin Dill are tracking the deer tick’s march across all 16 of Maine’s counties. Dill surveys fields in search of “established” populations, dragging what looks like a white flag on a stick over brush.

Already, another threat is looming. Scientists consider the Lone Star tick a better signal of climate change than its blacklegged counterpart—it has long thrived in southern states like Texas and Florida but is advancing northward. In Maine, tick ecologists have logged samples of the Lone Star species since 2013. Dill has surveyed fields and yards in search of settled populations, dragging what looks like a white flag on a stick over brush. He says the tick isn’t surviving Maine’s winters—yet.

It may be bringing new and unusual diseases here nevertheless. Patty O’Brien Carrier suffered what she describes as a bizarre reaction—itchy hives, a reddened face, a swollen throat—twice before learning that she has Alpha Gal Syndrome, a rare allergy to meat. In February, lab tests identified its source: a Lone Star tick bite. A “ferocious gardener” from Harpswell, 37 miles northeast of Portland, O’Brien, 71, believes she was bitten in her yard. She spends her time in the dirt surrounded by roses, daisies and other perennials. She notices more ticks in her garden, she says, much like she notices the ground thawing earlier each spring.

Dill has logged samples in this converted office for five years. “We’re still so inundated with tick-borne disease,” he says. “We’re trying to plug holes in the dam.”

In November, O’Brien pulled a bloated tick from her neck. It was as large as a sesame seed, concave-shaped and bore a white dot on its back—just like the Lone Star. “Its face was right in my neck and its legs were squirming,” she says. “It was quite disgusting.”

Now O’Brien performs the same ritual every time she goes outside: She applies tick repellant on her clothes and skin. She fashions elastic around her pants, and pulls her knee socks up. She adds boots, gloves and a hat.

“It’s like a war zone out there,” O’Brien says, “and I cannot be bitten by another tick.”