A motorist drives through heavy rain before the approaching Hurricane Harvey hits Texas during August 2017. Mark Ralston/AFP/Getty

This story was originally published by CityLab and is shared here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This month the cities of Austin and Seattle passed ordinances to tackle the already-here disaster of climate change. In Seattle, the city council passed a resolution to endorse adopting its own local version of the federal Green New Deal proposal, requiring the city to drastically reduce its greenhouse gas emissions while increasing affordability for low-income families. Austin, Texas, became the first city in the Deep South to declare a climate change emergency. The only other southern jurisdiction to declare this kind of emergency is Montgomery County, Maryland, which is just outside of Washington, DC.

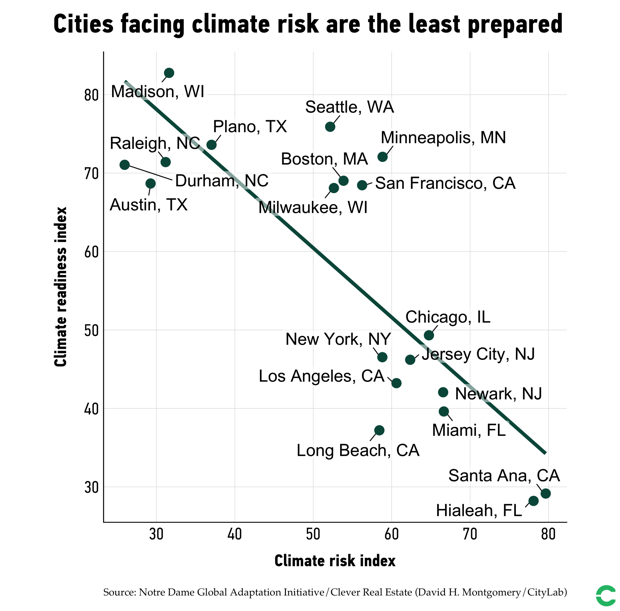

Yet when it comes to climate change disaster risk, neither of those cities really face the most serious problems—at least not when compared with other cities. A new study released this month, “How Climate Change Will Impact Major Cities Across the U.S.,” charts cities’ risk levels for incurring damage from climate-change-spurred floods, droughts, sea level rise, heat waves, and cold waves. Using data from the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN), Eylul Tekin, a research assistant for the online real-estate platform Clever, analyzed those risk factors along with each city’s plans to adapt to those weather hazards. She found that the cities that are most vulnerable to climate disasters happen to also be the least prepared for managing those catastrophes.

Both Seattle and Austin register pretty low in the risk factors and high on the readiness scales—with Seattle ranked among the top five cities already prepared for climate peril. The cities found at the lower end of the scales—high vulnerability and low preparation—are mostly ones in Florida and California, and the northeastern coastal cities in New York and New Jersey.

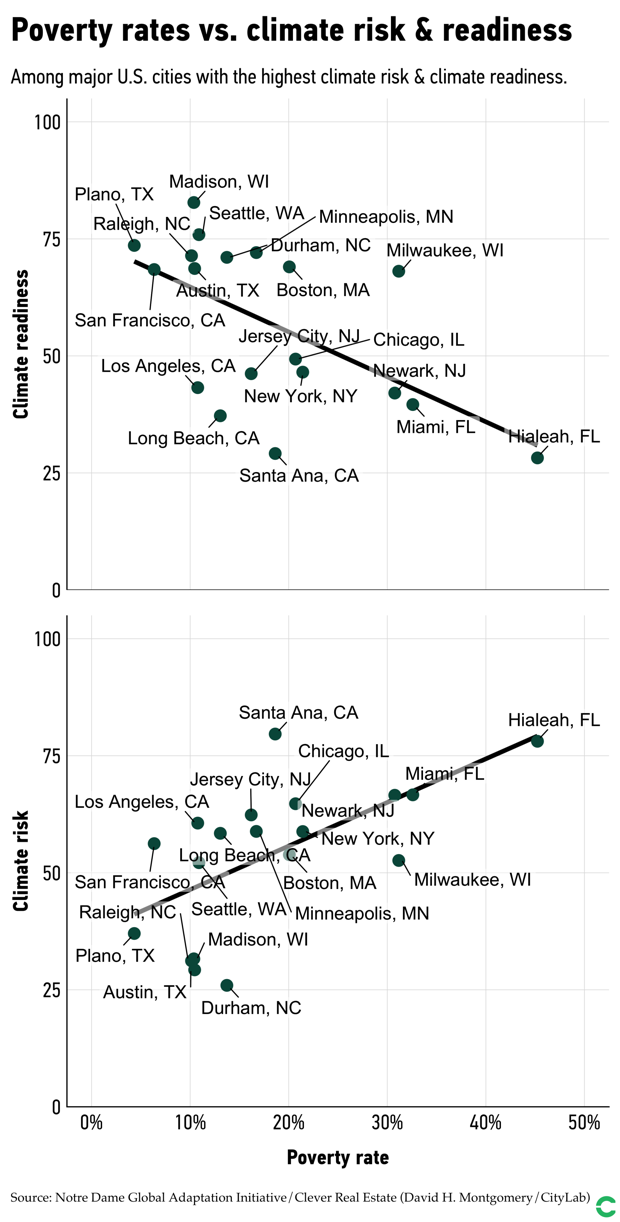

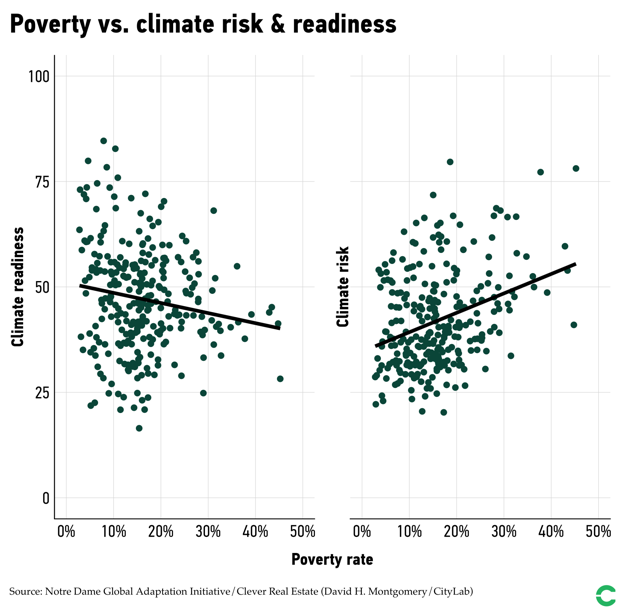

When examining the 20 cities Clever spotlighted by income, those with higher rates of poverty rank lowest in readiness and highest for risks. The top five low-readiness/high-risk cities have large black and Latino populations, while the five cities at the top of the rankings for climate readiness that rank lower on risk have larger white populations.

When looking at the poverty rates of the largest 100 cities, the pattern still follows: The poorer the city, the higher its vulnerability to climate change, and the lower its preparedness for those impacts.

Newark in particular is among the most vulnerable metropolises. It is among the top five cities in the Clever study that is likely to be compromised by an extreme cold event—a high “probability of six consecutive days in which the temperature falls below the 10th percentile of a city’s baseline period between 1950-1999″—which can also be triggered by climate change. Newark is also among the top five cities likely to experience extreme heat and sea-level rise impacts, both by 2040.

The Washington Post recently identified New Jersey as a state that has suffered unusually warm weather patterns in ways that “scientists do not completely understand,” over the past few years. Essex County, New Jersey, where Newark is located, has seen its average temperature increase by two degrees since 1895—the consequences of which means less of the albedo effect from snow and ice cover needed to reflect solar heat back into the atmosphere.

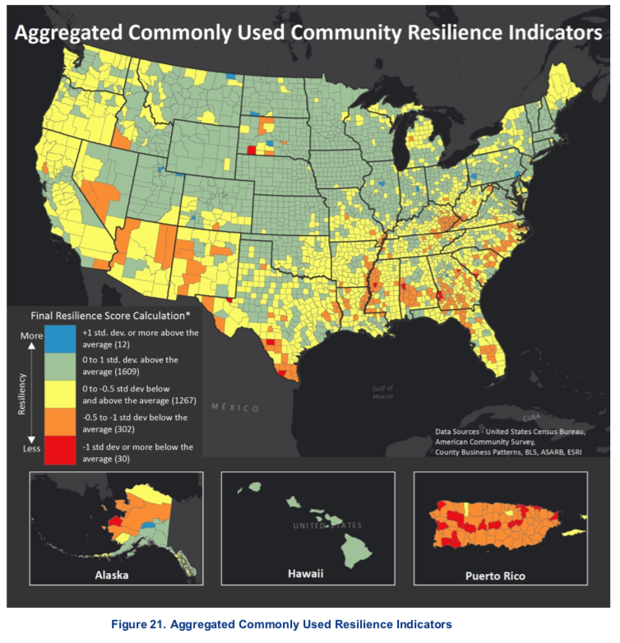

The Washington Post also identifies New York City as one in that northeastern cluster that is warming rapidly. While the Clever study places New York in the middle of the index in terms of climate change risks and readiness, another study conducted by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) cites two New York City counties as among the least resilient in the country—Bronx County and New York County (Manhattan)—when it comes to disasters.

For that study, researchers from the Argonne National Laboratory measured resiliency not based on whether they had plans for dealing with certain weather impacts, but instead gauged risk based on metrics such as unemployment rates, number of disabled residents, households without a vehicle, wealth, income inequality, and even the number of civil and social organizations per capita—all at the county level.

Community Resilience Indicator Analysis: County-Level Analysis of Commonly Used Indicators from Peer- Reviewed Research

Argonne National Laboratory

The counties that registered some of the highest resiliency scores tended to be those that scored high on the wealth index. Presidential candidate Andrew Yang was criticized for invoking wealth when asked about his climate change solution at a recent debate, but wealth matters according to the FEMA study.

“Circles of wealth tend to congregate with other circles of wealth and they create … an informal class system, particularly in urban areas,” said Kyle Burke Pfeiffer, an author of the FEMA study in an interview with Scientific American. “Wealth certainly correlates to being able to afford things like insurance and the ability to pull yourself up after a disaster and get a hotel room.”

But knowing and having a relationship with one’s neighbors matters, too, said Pfeiffer. New York County is home to one of the wealthiest jurisdictions in the U.S., Manhattan, and yet it ranked among the lowest scored for community resilience, mainly because of low vehicle- and home-ownership rates and a high level of transient residents, according to Scientific American. Bronx County scored even lower and was ranked among the worst 30 counties for resiliency. Both New York counties were outliers, as the majority of counties in the resiliency-poor groups were found across the Deep South and Puerto Rico.

Fortunately, New York City, still reeling from Superstorm Sandy, is on its way to mitigating future climate change hazards. Both the city and the state have committed to their own versions of the Green New Deal to reduce greenhouse gases, particularly from the numerous buildings patched across their urban landscapes. The city’s versionseeks to fulfill the social and racial equity mission of the federal proposal by emphasizing its universal healthcare offerings, expanding bank access for the underbanked, and tightening housing affordability and anti-displacement provisions from its 2015 OneNYC plan. The state’s Green New Deal is long on greenhouse gas reductions, but falls short on equity goals.

“To be clear, what we won is a strong climate bill; it is not a strong climate justice bill,” said Eddie Bautista, executive director of the Bronx-based New York City Environmental Justice Alliance, in a Facebook post about the new New York State legislation. Working with the NY Renews coalition, they pushed for 40 percent of funding from energy efficiency savings to be funneled toward communities considered the most vulnerable to climate change impacts and for strong labor protections for the jobs created in the state’s transition from fossil fuel to renewable energy. The bill that passed the state this summer only committed to 35 percent of “benefits” from energy savings and made no mention of labor protections at all.

A recent report from the urban planning and advocacy group Regional Plan Association found that some proposals found in Green New Deal-derived plans can actually be hazardous to low-income communities in climate-vulnerable pockets. In Central Queens, for example, the report found that measures such as building improvements can lead to displacement of poorer families who rent—roughly 70 percent of Central Queens residents are renters, and 35 percent of those already spend more than half their income on rent. Other measures, such as introducing electric public buses, often reach poor neighborhoods like Central Queens last. The report recommends that the city prioritize creating more green spaces, such as parks and rain gardens, and to expand visibility and accessibility of cooling centers throughout Queens.

Complications around the city’s network of 100-plus cooling centers is one of the major flaws of the city’s Green New Deal, says Bautista. These are places that people who don’t have access to air conditioning can go to cool off—usually libraries, community centers, and other public spaces. In 2018, Bautista’s group were disappointed when they tried locating these centers in their Bronx neighborhoods.

“We started calling the centers, because you can’t find them online until the day of a heat wave, which means you can’t plan ahead, and you have to have access to a computer,” says Bautista. “We found at least ten that didn’t know that they were city-designated cooling centers and didn’t know what we were talking about. Heat in particular affects people of color, and the city’s heat plans haven’t been updated to rectify the holes in the system.”

It’s problems like this that probably explain why New York isn’t higher on the recent resilience and readiness reports. New Jersey is having an even more difficult time dealing with heat extremes—an environmental catastrophe worsened by the lead water crisis currently afflicting cities like Newark.

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions and energy consumption should help reduce future climate change impacts, and those efforts are necessary. But places like Newark, New York City, and many cities across the South are experiencing climate change right now. It’s great that Seattle and Austin are getting their acts together, but the poorer, less-white cities are where the needs are greatest.