Workers install solar panels on the roofs of homes under construction south of Corona, CA.Will Lester/Getty

This piece originally appeared in High Country News and appears here as part of our Climate Desk Partnership.

Exactly a year ago, as the devastating Camp Fire swept through the foothills of the Sierra Nevadas. Frank A. Jr. Funes, a disabled 69-year-old Vietnam veteran, woke in the early morning hours to a phone call. It was his pastor, checking to see if he had evacuated. Immediately, Funes looked outside his window: His neighbor’s house was already burning, and the flames were licking at his own fence. He, his wife and their 4-year-old grandson rushed out the door. “I didn’t have time to grab anything,” he said. “The wind was blowing like crazy, and the fire was just right around the house.”

That day, Funes lost the house he had lived in for the last seven years. He has since found a new home 15 miles away. But the winds are a constant reminder of how vulnerable he and his neighbors are to wildfires. Already this year in Northern California, the Kincade Fire has burned nearly 78,000 acres and destroyed 174 homes. Now, whenever the gusts kick up, Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E), the region’s largest utility provider, preemptively cuts power to decrease the likelihood of a sparked transmission line starting a fire, as happened with last year’s Camp Fire. These shutoffs could last through the rest of November and for the foreseeable future, and Funes, like many others, feels helpless without electricity.

When PG&E shut off power in early October, 2.1 million people lost electricity. Amid the darkness and confusion of the next two days, residents caught a glimpse of what researchers call “the climate gap.” Those with solar panels, and more importantly, solar battery storage, fared pretty well during the outages. Tesla electric-car owners, some of whom had home solar systems, boasted about making pizzas in the midst of the blackout, while others watched movies in their parked cars. Meanwhile, those with limited means ended up buying expensive and polluting gas-powered generators at prices ranging from a couple hundred to a few thousand dollars. Many people, including some who rely on food stamps, were forced to throw out spoiled food. Those with medical disabilities—like Funes, who uses an electric wheelchair—worried about how long the outage would last and how much it would cost to keep the generator running. Just moving the generator in and out of storage was a physical challenge for him and his wife.

The state already has a plan in place to help remedy this disparity. In 2017, California designated funding to help disadvantaged residents and community organizations access new technology like solar batteries, through its Self Generation Incentive Program’s Equity Budget. It sounds like the perfect solution, one that by 2019, had accrued $72 million. The problem is, for residents, not one installation has taken place.

For years, so-called “early adopters”—people who buy things like electric vehicles, or install solar panels on their roofs—have been rewarded with rebates. But people who cannot afford the upfront costs miss out on the savings and new technology. As a result, by the end of 2017, solar panels were three times as likely to be found outside of disadvantaged communities, per capita, than in them, according to “Distributed Solar and Environmental Justice,” a research study conducted by Physicians, Scientists and Engineers for Healthy Energy (PSE). Meanwhile, low-income residents pay significantly more for electricity than early adopters do. That’s partly because a larger portion of their paychecks goes to energy costs, says Boris Lukanov, a senior scientist with PSE and lead author of the study—about 7.2% of a low-income family’s paycheck, compared to the average of 3.5% of their more fortunate neighbors pay. But it’s also because in places like California, where solar adoption is high, the cost of moving electricity around the grid falls on those who use more power. That includes disadvantaged residents, whose housing infrastructure might not be the most energy-efficient, and whose access to solar installations is limited, due to the high cost. Working-class communities often have the most to gain from sustainable energy, and not just for financial reasons: Low-income and communities of color are disproportionately impacted by high gas emissions.

Across the country, well-intentioned local and state governments hope to close that energy gap and assist their most disadvantaged residents through programs like the Equity Budget. But they keep running into problems. Stan Greschner, chief policy officer at GRID Alternatives, a nonprofit that works to make clean energy more accessible, said the reason is pretty simple: Low-income residents simply can’t afford any extra expenses. Even if a program like the Equity Budget covers half of the cost of a solar battery, the price is still too high for the struggling residents it’s trying to benefit. “If we don’t address the upfront cost barrier to adopting the technology, it will not reach low-income families, period,” Greschner said. “That was the biggest failure of the initial program.”

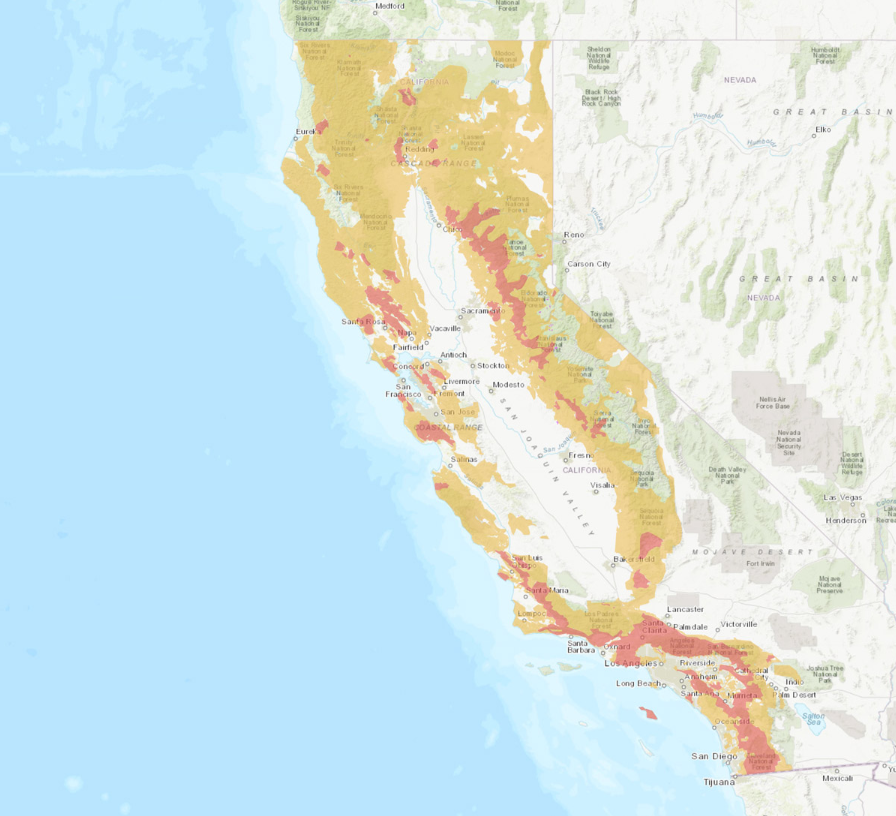

Areas with elevated (orange) and extreme (red) wildfire threat would be prioritized for solar subsidy programs.

California Public Utilities Commission

This past September, the California Public Utilities Commission announced sweeping changes to the budget in hopes that more people will be encouraged to apply. The solution, it turns out, is more nuanced than simply having to pay for the upfront cost of solar batteries. Starting in 2020, the program will aim to cover nearly all of the costs for a battery installation for residents who live in a disadvantaged or low-income community.

Disadvantaged communities, as defined by California, face a “combination of economic, health, and environmental burdens.” In addition, residents who meet that threshold and live in high wildfire-risk zones like Los Angeles or the Sierra Nevada will get their energy storage needs met through yet another initiative, the Equity Resiliency Program, which provides an extra $100 million in funding. Crafted in anticipation of events like this fall’s wildfires and blackouts, it’s aimed at providing disadvantaged and medically vulnerable residents like Funes with greater energy resiliency. Tribal nations will also be eligible for this new funding.

Some structural improvements make the program easier to apply for. And because funding can now be coupled with existing solar panel incentives aimed at disadvantaged residents, people can take advantage of both programs at the same time. This is good news for renters, too: Forty-three percent of California’s low-income residents live in multi-family housing, which will now be able to pair existing solar panel subsidies with storage options. The savings in solar energy would be passed down to tenants, and the buildings could serve as “resiliency centers” for the greater community whenever an outage hits.

How the utility rolls out the new program “could very well be the key to success or failure of this program,” said Greschner. Disadvantaged communities have often been targets for financial schemes and are understandably wary of flashy incentives. One recent scam, tried to peddle fake solar installations to large Spanish-speaking immigrant populations. And many residents won’t even know about the program unless the marketing materials are available in a language they can read—something that is so far uncertain in the new marketing plan. In Lukanov’s study, the authors stated linguistic isolation was strongly associated as to whether or not residents had solar panels. “In a lot of communities, the heads of households are non-English-speaking,” Greschner said. “They don’t respond to a utility bill insert (in English) that says, ‘Hey, you qualify.’ ” They need to be reached in different ways and in their language, and so far, programs in the state have fallen short in that respect, Lukanov said.

Nonetheless, for people like Funes, who heard he could add battery storage to his house once the new Equity Budget rolls out, the changes couldn’t come quick enough. He got his solar panels last year, but without storage, they are useless during the blackouts. “I am praying for the batteries to go through,” he said. Lately, he’s been distributing pamphlets to his neighbors, telling them about the solar panels and the possibility of battery storage. But for now, he’s left to the whims of the Santa Ana winds, and of PG&E. “(The power) is going to be going out all the way through November,” Funes said. “I read in the newspaper and on the internet that it is going to be this way for 10 years.”