Marisa Endicott

I meet Les Tso on a corner in San Francisco’s SoMa district on a wet Thursday afternoon. He pulls his silver Isuzu SUV into an alley. “Today because it’s the first rain, people are going to be driving cluelessly—there are a lot of Uber and Lyft drivers that come from out of the area,” Tso warns me. “Makes it more exciting, I guess.”

Ride along with Les Tso on the latest episode of Bite podcast:

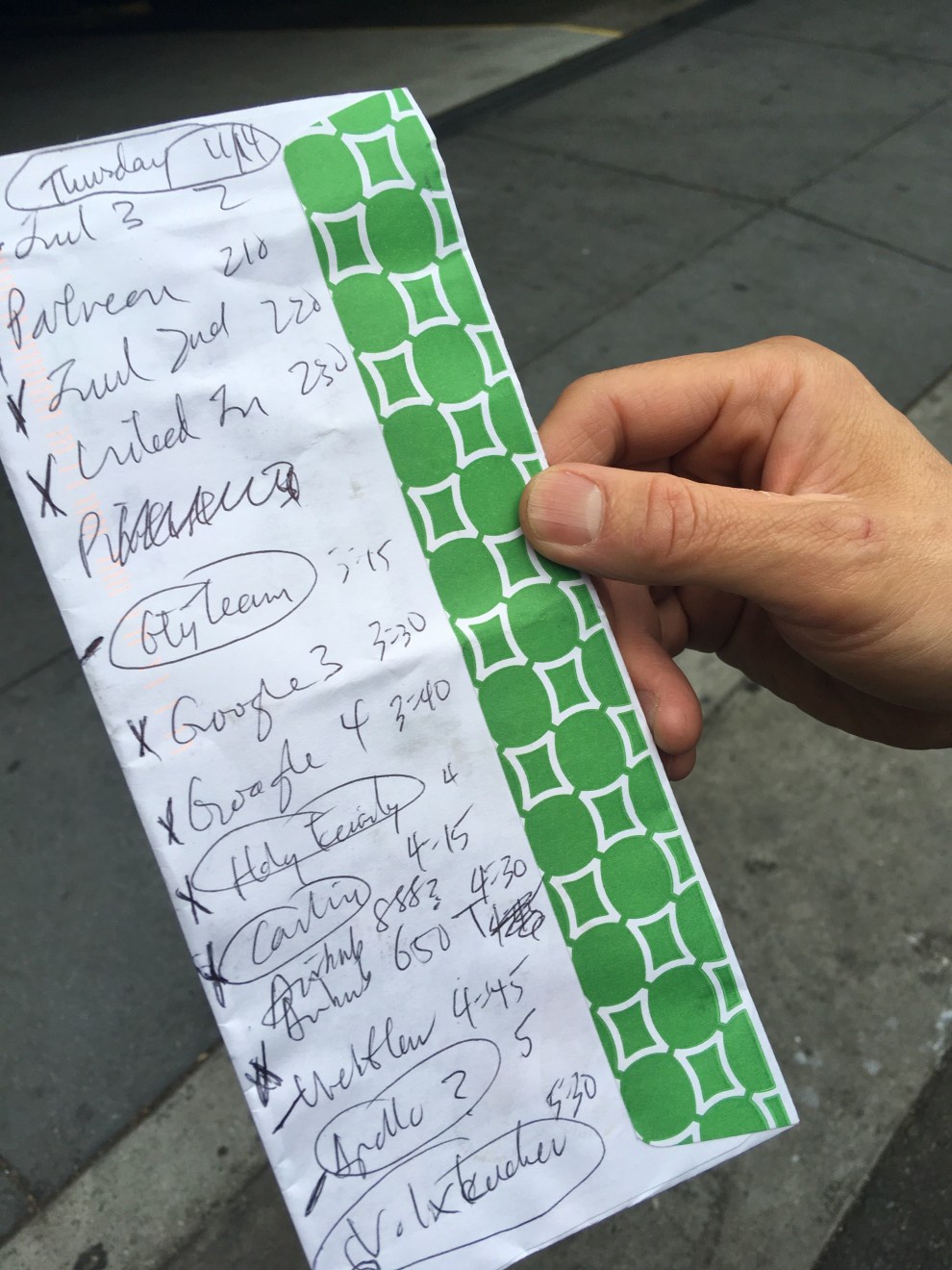

Tso works as a driver for Food Runners, a nonprofit that picks up leftover food from grocery stores, companies, events, and restaurants and brings it to organizations working to feed the hungry. For four hours every weekday, Tso braves the worst of Bay Area traffic to makes his 80 to 90 pickups (an average of 16 a day), primarily from tech companies—including Google, Juul, and LinkedIn—that have become an omnipresent force in the city.

Marisa Endicott

Food Runners was founded in 1987 by a small group of friends who started picking up food from a few businesses to bring to local shelters and food programs. Today, they rescue over 17 tons of food, enough to serve more than 20,000 meals, every week. The organization is made up of just a few employees and a network of about 250 volunteers who make more than 700 food runs weekly.

Even with Food Runners’ small army, there’s still more leftover food than anyone knows what to do with. “I think everyone who does this is incredulous about how much there is. It’s just crazy. And I’m only seeing the tip of the iceberg,” Tso tell me. Food Runners even launched an app to keep up after donations surged as the tech boom took hold; in 2014, the organization saw a 50 percent increase in donations.

The increasing pressure on businesses—especially in the tech sector—to offer employees free meals as a perk creates a challenge when it comes to food waste. “If you’re telling your people you’re going to feed them at work, and you run out, that’s really bad, right,” Tso says. “So, if you can’t run out, you have to over-project.”

But it’s not just tech company cafeterias generating this overabundance. In the United States, we waste about 40 percent of our food supply. That’s 400 pounds of food per person every year, collectively costing us up to $218 billion annually (or 1.3 percent of the GDP). “We’ve gotten to a place where our culture expects food now and expects abundance, and we expect it to be beautiful and all of these things,” says Andrea Collins, a sustainable food systems specialist at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). “I think we’re starting to see a turn on that. But we’ve built all of these inefficiencies into our system as it stands now. And that’s the piece that has led to so much food waste.”

And food waste is an often overlooked contributor to climate change, responsible for 8 percent of our global greenhouse gas emissions. Reducing it is considered one of the most important ways to mitigate the climate crisis. “That’s one of the pieces that’s missing from our climate conversation,” Collins says. “Food waste is such a big contributor on the global scale, and it’s something that’s accessible now.”

After avoiding buying or making too much food in the first place, food rescue—like what Tso and Food Runners do—is the best way to prevent wasted food, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. It’s also critical to solving hunger in the United States. A 2017 report by the NRDC found that less than a third of the food we throw out would be enough to feed the 42 million Americans without access to enough food.

Tso has a lot of respect for the people in San Francisco that hustle to find ways to keep feeding the many people who cannot afford to feed themselves or their families here. A lot of groups host their food programs at churches and libraries, he tells me, since these institutions have space in a city where real estate is valuable above all and almost impossible to come by. Tso is happy to do his small part. “I’m helping them help people,” he says. “I’m not there feeding people. They’re feeding people.”

Marisa Endicott

The job is messy; his car is full of gloves, bags, and 15 towels. Once, he went to pick up food from a restaurant downtown and was caught by surprise when he lifted a container meant for solid foods and a hot liquid splashed out instead. “They put frickin’ chicken noodle soup in a pan, and the whole thing just fell on me,” he remembers, laughing. “You have to shrug it off. Can’t let it bother you for more than five minutes.” He put a towel on his seat and kept driving. That pretty much sums up Tso’s attitude—keep moving.

Sometimes people don’t show up with the donated food. Sometimes they show up with too much, and Tso has to scramble to find places to take it. Trader Joe’s once gave him 26 cases of bananas. They were still good, but a store mandate keeps them from selling the ones with brown spots, Tso says. No single program could make use of that many bananas, but Tso couldn’t watch them go to waste, so he divided up the haul between four or five places that would take them.

Tso knows where certain food will be most appreciated. On the day I ride with him, he saves some fish for a low-income apartment complex in the Mission because he knows they love it. Close by, a vegetarian program will take all the unwanted quinoa he always gets. One family food pantry at a church can’t take anything with nuts since kids are more prone to allergies. Once in a while, companies will have less to donate than expected. “Sometimes donors feel bad because they have like two pans,” Tso says. “And I say, ‘No, that’s cool! That means you hardly have any waste. That’s awesome.'”

Marisa Endicott

Marisa Endicott

At 54, Tso has had a lot of jobs in his life. He worked for Safeway for 15 years. He was an analyst at Dr. Pepper and worked in category management—the science of shelving—at Pepsi. He’s in the wine business, got a degree in English Lit, and has an MBA. He can tell you about soda business monopolies and why Costco rotisserie chickens are so cheap. But he seems to have found real fit at Food Runners. “This is one of the better jobs I’ve had in my life just because you feel good doing it,” he says.

After working with Food Runners for a year, Tso has developed a theory on the best kind of business to start in this city: “Cater to high tech companies.” He’s not the only one with that idea, and it’s changing the food scene in the Bay Area. Tech companies have lured top restaurant talent to their in-house kitchens with good benefits and better hours than almost any typical eatery can offer. Many food businesses have pivoted to catering. They’re turning to ghost kitchens (stripped down commercial kitchens without retail space) to minimize exorbitant rent costs and better target the reliable company lunch market. Broker businesses have cropped up to connect caterers to offices (for a hefty fee). And even the business of cutting food waste is taking off. In 2018, food waste startups garnered more than $125 million in venture capital and private equity funding.

But in all this madness, Collins sees opportunity, and the solutions don’t have to be high-tech. “If we’re signaling an expectation of abundance, we’re going to see more abundance and we’ll see more waste. If we’re instead signaling that sustainability is a core component of what we expect from our employers or what we expect from the businesses that we shop at, we’ll then help drive change on a system-wide scale,” Collins says. “Workplace cafeterias can be an amazing place to make a big amount of change because you’re serving a lot of food all at once. I think that’s actually a potential place where change can happen pretty quickly.”

Some companies have taken significant steps to curb waste. Google started using equipment to track and measure food consumption, and says it’s saved 6 million pounds of food over the last 5 years. (During our ride-along, Tso gets his biggest haul of the day from Google.) In general, companies with in-house kitchens can better manage leftovers since cooks can repurpose ingredients and adjust inventories. When we stop at LinkedIn, there’s only six or seven trays to pick up even though they feed 2,000 people at lunch and have to account for employees bringing friends.

Marisa Endicott

As we zigzag between pickups and deliveries, the city’s wealth gap is even more glaring than usual. Between runs to multiple Juul and Google buildings, we drop off at low-income apartments for veterans and a church food program that serves 150 mostly homeless families every Friday. Then we pick up at a tech company mid-party that’s in the process of expanding to another floor in the building. It gives you whiplash.

Tso reminds me of the closet at Juul, which was fully stocked with snacks and drinks. “That’s tech company, classic, right? So much,” he laughs. “But then you see people out in the streets, you know? It’s raining. They don’t have any shelter and stuff. It’s like, man…”

But Tso isn’t looking to cast judgment. He wants everyone to feel like they’re in it together. And through him, they sort of are. “You want people to feel good that you’re picking up food from them, right? Leave a good taste in their mouth. And then the people that you give food to, you want them to feel good, too.”