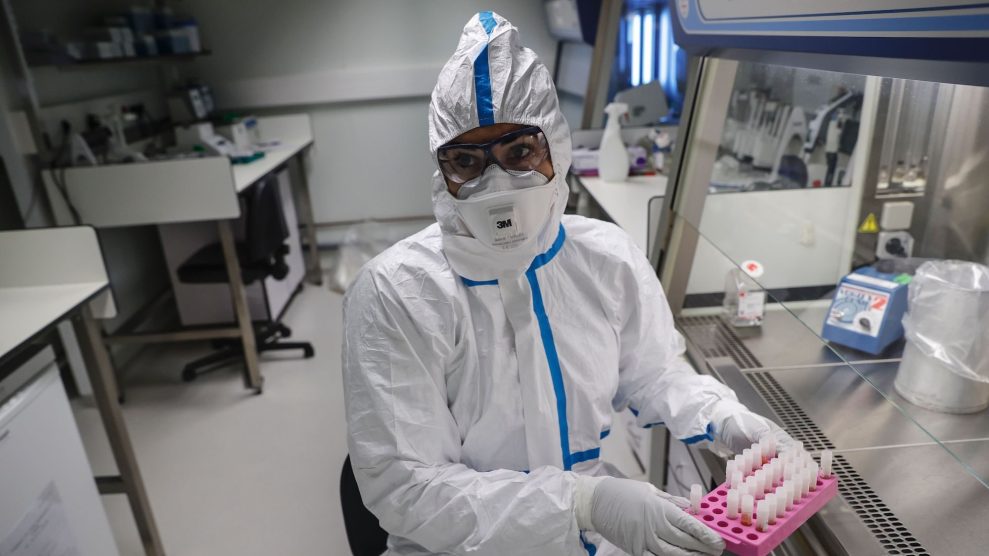

A laboratory operator wearing a protective gear handles patients' samples in a laboratory of the National Reference Center (CNR) for respiratory viruses—including coronavirus—at the Institut Pasteur in Paris on January 28, 2020.Thomas Samson/Getty

Since it was first detected in December, in Wuhan, China, the number of known people infected with the coronavirus has ballooned to nearly 6,000, with new cases quickly turning up in Asia, the Americas, and Europe. As of Tuesday, 100 people have died from the illness in China, where the government is scrambling to detect it and contain the spread—speedily erecting hospitals and putting cities on shutdown mode. Other countries are curtailing international travel to China, which has agreed to allow specialists from the World Health Organization to assist in disease mitigation.

As the public health crisis becomes more serious, so too has the desire for news about the virus. Enter now, a high volume of unsourced and often inaccurate information feeding that appetite. Some of the traffic focuses on the speed of how the illness is spreading, or the response in China, but some of the most active chatter has been around potential, albeit unproven, treatments for the illness, which, because it is a virus, is unresponsive to antibiotics.

People are not just barricading themselves inside #Wuhan, they are also trying to escape the quarantine zone, in this video they are repelled by police.

How many have made it out?#coronavirus pic.twitter.com/i2xswjCIZr

— Darren of Plymouth 🇬🇧 (@DarrenPlymouth) January 28, 2020

Have we learned nothing from this game? Close all Harbours and Airports immediately. #coronavirus pic.twitter.com/cDtAiB0M7F

— Nathan Morris (@nathanmorris_) January 28, 2020

Fucking hell there no way #China has this under control #coronavirus 😷😷😷

Not looking good for the whole human race 😬😬😬 pic.twitter.com/IezQlij9ON

— Brylcreem Boy (@Brylcream_Boy) January 28, 2020

Some stories reported that Chinese doctors have discovered a cure for the coronavirus in a class of HIV drugs called protease inhibitors. Reuters reported that an HIV medication was being tested to treat coronavirus symptoms, but that is a far cry from any kind of cure. But then the story escalated and dubious publications like the New York Times Post and the UK-based tabloid the Express carried this claim further, saying that an HIV “wonder drug” called Nelfinavir was being used according to the Express, “‘somewhat successfully’ to tackle coronavirus.” Nelfinavir was not one of the HIV medications that was being tested, according to Reuters. Nonetheless, the internet seized on the information.

HIV drug could STOP deadly disease Coronavirus cure in major breakthrough – REVEALED yesterday

— DARINE CHAHINE (@dareenshaheen) January 26, 2020

▂▃▅▇█ Coronavirus Cure █▇▅▃▂

HIV drug (Nelfinavir/Viracept) could STOP deadly disease in major breakthrough – REVEALEDhttps://t.co/PKAl24Rc4k— JD (@JDiviv) January 28, 2020

Multiple doses of Nelfinavir stopped the #CoronaVirus from spreading. One patient in Shanghai is cured.

— Richard Ker (@richardker) January 25, 2020

Even though these publications are far from the mainstream, both of the articles supported their stories with apparent insights from experts in the field. One of them was Dr. Michael Mina, an epidemiologist and assistant professor at Harvard School of Public Health. The Express article said he “revealed experts…are using protease inhibitors ‘somewhat successfully’ to tackle coronavirus.” I called Dr. Mina to find out more about this research to see how his work squares with other stories about possible coronavirus treatments mentioned in other articles.

First of all, Dr. Mina was surprised to see that he had been quoted as one of the sources for this information, since he knows that the coronavirus has no confirmed cure. In fact, during a recent conversation with a reporter at WebMD, he explicitly discussed what he described as the “unsubstantiated claims on Twitter that [protease inhibitors] were being used.” Protease inhibitors may have been used to treat SARS, a related but distinct illness, he says, but there is no evidence that these could be used for the coronavirus.

I told Dr. Mina that he had been quoted in the Express. “I really want to know where these are coming from,” he says, adding that the conversations he’s seen on Twitter show “there’s lots of fearmongering going on about global pandemic, a catastrophe happening or about to happen.” He suggests that at this point, the only message that seems to emerge from the “tremendous amount of information being thrown around,” is that the coronavirus “is distinct from any virus from the past.”

So I asked Dr. Mina, about teasing out fact from fiction in the onslaught of information. How does one determine the seriousness of the infection, much less the cure? Officially, more than 5,900 individuals are infected with coronavirus, though some experts suspect underreporting. But, I told him, one professor at Imperial College in the United Kingdom told the Guardian that 100,000 people could have coronavirus. That number has not yet been confirmed, but Mina says that if it turns out to be true, this could be good news. A fatality rate of 100 in 100,000 is significantly lower than 100 in 2,500. “If we find out that the virus has infected many more than we know, that means it’s even less pathogenic than we think,” he says. “It would be more like seasonal flu is every year.”

What about how rapidly the coronavirus is spreading? Yet another source of misunderstanding. Across Twitter, users following the disease have paid close attention to what is known as the “r-nought”—often expressed at “R0.” That’s a data point representing the rate by which a disease spreads. To understand this better, I turned to Dr. Angela Hewlett, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Nebraska Medical Center and member of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. She explained, “It’s essentially the number of transmission events of a disease per infected person.” An r-nought of three, for example, means “one infected person is likely to infect three people.” Hewlett says that actual r-nought of this coronavirus outbreak isn’t clear. When I asked Mina, he said he thought it was somewhere between 1.5 and 3. Though, it’s important to note than the r-nought doesn’t take the severity of an illness into consideration.

In the Twitter universe, however, users are using the r-nought to calculate possible trajectories of the spread of the virus, envisioning a global pandemic, while it’s still uncertain whether the coronavirus will turn out to be more comparable to a seasonal illness like the flu in terms of mortality rates.

BREAKING NEWS: The #coronavirus exceeds SARS with R0=2.5, Harvard epidemiologist, Dr. Eric Feigl-Ding reports. And now we have the 4th generation confirmed cases in China. The US government should start the emergency preparations immediately! pic.twitter.com/F0pi2BLv6s

— Max Howroute▫️ (@howroute) January 25, 2020

Not only is over-speculating on how quickly the illness is spreading unproductive and potentially fear-mongering, even a high r-nought needs to be properly contextualized. “We don’t know how many people are being infected and staying perfectly healthy throughout the process,” says Mina. Hewlett points to other prominent deadly diseases that have much higher r-noughts than coronavirus. “It’s important to put all of this in context,” Hewlett says. “Someone with measles has an r-nought of 18. Lots of diseases are much more contagious than it looks like this novel coronavirus will be.”

The bottom line is that epidemics such as the coronavirus can often bring out the worst in social media. When tools from the science or medical worlds enter the public discourse without being fully understood, or put in context, they can be misused. “Social media allows buzzwords to enter the layperson domain,” Mina says, “which leads to a tremendous amount of misunderstanding and, frankly, fear.”