Northern Right whale off Grand Manan Island in Bay of Fundy, New Brunswick, Canada.Francois Gohier/Getty

This piece was originally published in Yale Environment 360 and appears here as part of our Climate Desk Partnership.

Artie Raslich has been volunteering for seven years with the conservation group Gotham Whale, working on the American Princess, a whale-watching boat based in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn. In that time Raslich, a professional photographer, has glimpsed a North Atlantic right whale, the world’s rarest cetacean, only twice. The first time was an unseasonably warm December day in 2016, when he managed to snap a striking image of a right whale’s dark tail against the backdrop of the New York City skyline. “That was a beautiful shot,” Raslich says, proudly. The second was just a few weeks ago, in early October, roughly 3 miles east of Sea Bright, New Jersey.

Unfortunately, both whales had suffered an increasingly common fate: They were entangled in fishing ropes and were likely to die.

The North Atlantic right whale is one of the most endangered species on the planet. Scientists announced last month that there are only about 360 of the animals left, down roughly 50 from the previous year’s survey. They live along the East Coast, from northern Florida to Canada, where the 50-foot-long, 140,000-pound leviathans must navigate through millions of commercial fishing lines—primarily lobster traps—and one of the world’s most crowded shipping channels. Too often they become tangled in those lines, or are struck by a ship. The fight to save them, led by biologists and conservation groups, has grown urgent—in the water and in the courts.

Scientists are using cutting-edge acoustic technology to monitor right whales and identify where they are coming into contact with ships and fishing lines; rescue teams in the United States and Canada are scrambling to disentangle animals when they’re spotted; and environmental advocates are making significant headway suing state and federal agencies to enforce provisions of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and Marine Mammal Protection Act, which were written to protect the whales from extractive industries like lobster fishing.

“The next five years are critical,” says Sarah Sharp, a veterinarian with the International Fund for Animal Welfare. “If we don’t do anything, this species will be functionally extinct in 25 years.”

Historically, as many as 21,000 North Atlantic right whales lived off the East Coast of the US and Canada. But by the early 1890s, the right whale, so named because commercial whalers considered it “the right whale to kill”—relatively slow, easily visible from the coast, and full of blubber so their carcasses would float—were on the brink of extinction.

Whale hunting was banned in the US in 1972, but humans remain the right whale’s biggest threat. In Maine alone, the creatures must traverse approximately 400,000 vertical buoy lines attached to roughly 3 million licensed lobster traps.

The buoys can get lodged in their baleen, the filter-feeding system inside their mouths. As the animals roll and spin, trying to free themselves, the ropes wrap around their bodies. The lines cut deeply, sawing into bone and slowly amputating fins or tails. “It’s a slow, painful death,” says Sofie Van Parijs, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration scientist.

Once a whale becomes entangled, it can continue to pick up other gear, including lobster traps and crab pots, as it moves through the water column, a snowball effect with deadly consequences. Even if the gear doesn’t drown the whale, carrying such extra weight can weaken the animal and interfere with its ability to feed and breed.

Scientists have documented more than 1,500 entangled right whales since 1980. In fact, estimates suggest almost 90 percent of the surviving population has been entangled at least once, and more than half have been snagged twice.

Charles “Stormy” Mayo, a co-founder of the Center for Coastal Studies in Provincetown, Massachusetts, developed some of the techniques used to remove whales from fishing gear, including deploying large floats to slow the animals and prevent them from diving while rescuers lean out of their boats and cut the whales free. It’s a dangerous job. In July 2017, a fisherman volunteering on a whale rescue team in Canada was crushed to death by the animal’s tail. Such rescue efforts have saved dozens of whales, says Mayo, “but disentanglement is not the answer to saving the species. The answer is keeping the whales out of fishing gear and from being hit by ships.”

Scientists attempting to better pinpoint where right whales encounter fishing gear and ships are using underwater acoustic technology to record the whales’ characteristic groans, grunts, and burps. Hydrophones mounted on the ocean floor collect data about their movements, while autonomous underwater gliders relay their calls in near real-time, providing opportunities to alert mariners to slow down when whales are in the area.

Peter Corkeron, who leads the whale research team at the New England Aquarium’s Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life, says acoustic studies have revealed an important finding: North Atlantic right whales, which historically spend summers in the Gulf of Maine and the Bay of Fundy, are increasingly venturing north to the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, a shift likely fueled by climate change. “The Gulf of Maine is like a giant bathtub filling up with hot water,” Corkeron says, making it less habitable for marine life, including the phytoplankton that right whales eat. “The whales are following their food to the Gulf of Saint Lawrence,” he says, “and that’s not working out so well for the whales.”

Since the whales did not historically frequent the Gulf, few measures existed to protect them prior to 2017. That’s when whale deaths suddenly skyrocketed, in what scientists are calling a “mass mortality event.” In three years, 31 whales have died in the US and Canada, more than half of them in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. In response to the deaths, the Canadian government has implemented speed restrictions for boats, seasonal and temporary fishing closures, and new rules for fishing gear to improve whale safety. It also finalized the designation of the Laurentian Channel Marine Protected Area, a deep submarine valley in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence that is a biodiversity hotspot and critical migration route for whales. However, industry objections to the plan resulted in it being drastically reduced in size to accommodate fishing interests, and largely open to oil and gas development. Some scientists now question whether the designation achieves the intended purpose of conserving wildlife.

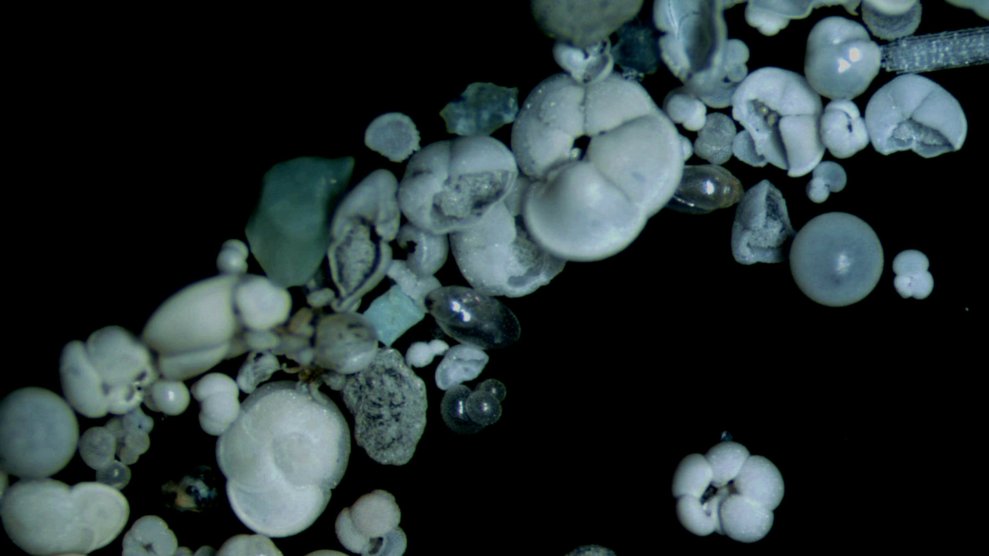

So far this year, one right whale has been reported dead in New Jersey, the victim of a ship collision, and three right whales entangled in fishing lines have been spotted between there and Massachusetts. One of them was Artie Raslich’s whale. On October 11, Raslich was at his usual post on the left upper deck of the whale-watching boat. He saw a faint blow, and trained his camera on what appeared to be a “beat-up humpback.” But he quickly realized that the animal’s dark body was dotted with rough white patches, called “callosities.” The callosities, combined with a V-shaped spout, deeply notched tail, and absence of a dorsal fin confirmed that it was a North Atlantic right whale.

When Raslich downloaded his photographs to his computer that evening, he zoomed in and saw that the whale was wrapped in fishing line and badly injured. He sent his photographs to researchers at the Center for Coastal Studies and Marine Mammal Stranding Center, who cross-checked the pictures with a photographic catalog of known right whales, showing each animal’s unique pattern of callosities, comparable to human fingerprints. They determined that the whale was a four-year-old male, the calf of a 19-year-old female named Dragon who was last spotted in late February 2020 emaciated and pale, with a buoy lodged in her baleen.

Corkeron says it’s unlikely that either Dragon or the calf could survive their injuries. “They’re dead whales swimming.”

The loss of Dragon is especially tragic because only 94 breeding females remain, according to recent estimates. And those females are having fewer calves. Historically, North Atlantic right whales have given birth roughly every three years, but more recently females are birthing calves only every six to eight years, Corkeron says. Scientists do not know why the females are having fewer calves, but they suspect the lower production is related to changing habitat and stress caused by entanglements and ocean noise.

“The story of the North Atlantic right whale is complex, but it boils down to second-grade arithmetic,” says Stormy Mayo. “The number of animals born minus the number that die gives us a trajectory. Right now, the arrow points to zero—extinction—and that’s a very chilling finding.”

The right whale’s fate may ultimately depend on the courts. In 2019, US District Judge James Boasberg ruled that a plan to reopen gillnet fishing south of Nantucket for the first time in decades, without appropriate analysis required by the Endangered Species Act, was unlawful. It was a major victory for conservationists.

Last April, conservationists won again, when Boasberg ruled that Massachusetts regulators are violating the ESA by approving licenses for fishermen using vertical buoys, such as those deployed with lobster traps. The judge ordered an ESA-mandated analysis of the lobster fishery that takes into account the full scope of its harm to right whales, and directed fishery managers to issue new protections for North Atlantic right whales by the end of May 2021.

Erica Fuller, a senior attorney with the Conservation Law Foundation, one of the nonprofits that filed the lawsuits that led to Boasberg’s rulings, says her group’s goal is to reduce the number of opportunities for right whales to hit vertical buoys. One strategy is to have fishermen transition to so-called ropeless fishing gear, allowing lobster traps to be retrieved using a remote acoustic signal to trigger their release. The devices—consisting of stowed buoys, rope, and lift bags—operate similar to keyless car entry; a radio signal unlatches them when a fisherman comes to retrieve his gear, and the traps float to the surface.

However, many fishermen oppose going ropeless. Dave Casoni, the secretary and treasurer for the Massachusetts Lobstermen’s Association, says he tested the gear and found it “too time consuming and expensive.” Massachusetts lobster season is only six months long, and “if I spend a third of my day rigging these acoustic releases, that takes even more off the bottom line,” he says. “Rigging 800 traps [the maximum allowed] could cost more than half-a-million dollars.”

Casoni says fishermen have always been cooperative with restrictions to protect whales, and proactive by helping to investigate methods and technology that are practical. “We’re doing everything we can to minimize encounters with whales,” he says. “We’re using weaker ropes, lines that sink [rather than floating freely], and breakaways on buoys so they’ll pull through the whales’ baleen, instead of getting caught. We take all of these conservation measures, and yet there’s pressure to make us do even more.”

Fuller and other ropeless proponents are sympathetic, but they say that public and private subsidies should help fishermen adopt the new technology.

Still, fishermen are nervous about what may happen in the courts. They’re keeping a particularly close eye on a Massachusetts lawsuit filed by a controversial whale advocate named Richard “Max” Strahan, a self-taught scientist and amateur lawyer with wild gray hair and missing front teeth who calls himself the “Prince of Whales.” He sued the state of Massachusetts in federal district court, seeking to end the use of vertical buoy lines. Last July, the judge in that case ruled that state fisheries regulators are violating the Endangered Species Act by allowing vertical lines without first receiving an “incidental take” permit from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (Incidental take is defined as the killing or harming of an endangered species due to an otherwise lawful activity.) The judge stopped shy of shutting down the fishery, allowing it to stay open while the state seeks a permit. The proceedings are ongoing, with a trial scheduled for June 2021.

“The judge is worried about the economic consequences of enforcing the law,” Strahan says. “But if she rules that a commercial activity or licensed act is taking an endangered animal without a permit, that activity must stop until it can be figured out what to do.”

The solution he supports is to radically transform a centuries-old business. “This is not about shutting down the lobster fishing industry,” he says. “It’s about creating a marketplace for whale-safe fishing.”

Strahan wants states to change the current lobster license policies to favor “green lobstermen” and fishing companies willing to invest in ropeless gear and other methods that are safer for whales.

As the court fights drag on, though, the struggle in the water continues.

Recently, flight crews searching for Dragon’s entangled calf spotted another right whale in trouble south of Nantucket. The 11-year-old male, known as Cottontail, had a line wrapped over his head, through his mouth, and extending more than a hundred feet beyond his tail. The Center for Coastal Studies dispatched a rescue team to remove the gear. They succeeded in shortening the trailing line, but since they could not remove it entirely they attached a satellite transmitter to the whale so rescuers can try again when conditions are favorable.