Mother Jones illustration

The website Women for Natural Gas is a pink-tinged, fancy-cursive-drenched love letter to the oil and gas industry. A prominently featured promo video shows women in hard hats and on rig sites. “Who’s powering the world? We are!” enthuses the narrator. Viewers can click through to a “Herstory” timeline of women working in the oil sector. Another page, about the group’s grassroots network of supporters, announces, “We are women for natural gas,” and shows three professionally dressed ladies alongside their testimonials. There’s a Carey White gushing, “The abundance of oil and gas in Texas helps keep prices at the pump lower.” One Rebecca Washington raves, “Natural gas is a safe, reliable source of energy that provides countless numbers of jobs.”

But there’s a catch: The women don’t exist.

A few months ago, I received a tip to look into the website’s testimonials—my tipster suggested that the group was using stock photos to represent the women who had supposedly contributed testimonials about natural gas. A reverse image search revealed that two of the images were indeed stock photos. The third, supposedly of a woman named Carey White, was the professional headshot of Jessi Hempel, a senior editor at-large at LinkedIn. The photo had been published in a brochure when she appeared at a 2020 Tupelo, Mississippi conference for landscape architects.

When I contacted Hempel, she said she had never contributed any photo or testimonial to Women for Natural Gas. She said she found it “incredibly disturbing” that the group was using her image without her permission. “Thank you so much for discovering my image on a website I guarantee you I never would have clicked on,” she told me. Texans for Natural Gas, an oil and gas industry group that created Women for Natural Gas, never responded to Hempel’s or Mother Jones’ inquiries about the photo. The group did eventually swap out Hempel’s image, but only after being contacted twice by a lawyer for Hempel’s employer, LinkedIn. Even then, the testimonial attributed to Carey White remained unchanged—the only difference was that it was accompanied by a new smiling woman’s headshot.

A closer examination of Women for Natural Gas revealed that for the last year, the group has cycled through different headshots of women and quotes. My reporting suggests that it’s unlikely that the testimonials are genuine. Back in May, the site showed testimonials from Natalie White, Carey White and Natalie Smith, with identical quotes for the two Natalies (notwithstanding the overlapping names). By August, the names had diversified, a little, to Rebecca Washington, Natalie Smith, and Carey White, and the identical quotes had also changed again.

The original shop hired for Texans for Natural Gas communications is FTI Consulting, a global consultancy with fossil fuel clients and the subject of Hiroko Tabuchi’s New York Times investigation last month. Tabuchi found that FTI has set up at least “15 current and past influence campaigns promoting fossil-fuel interests in addition to its direct work for oil and gas clients.” These campaigns are run by paid consultants, Tabuchi writes, and “often obscure the industry’s role, portraying pro-petroleum groups as grass-roots movements.”

The NYT reported that FTI Consulting’s spokesperson Matt Bashalany admitted to Texans for Natural Gas’ use of stock photos, but maintained the supporters and testimonials were real. I went back to FTI Consulting to ask whether they would stand by the claim, given the screenshots I had of the website swapping out photos and quotes throughout the year.

In response, FTI Consulting distanced itself from the project all together. Bashalany emphasized that the website was created by a separate contractor hired directly by the client, and that the testimonials came in through an online form managed by a website contractor. Bashalany directed me to the oil and gas companies that sponsor Texans for Natural Gas, listed on the website, which include XTO Energy (a subsidiary of ExxonMobil), EOG Resources, and Apache Energy. Texans for Natural Gas never returned my calls and emails, and the oil companies declined to comment for the story.

As of publishing, the site still had the three testimonials up, but removed the headshots all together for pink cartoonish outlines of women.

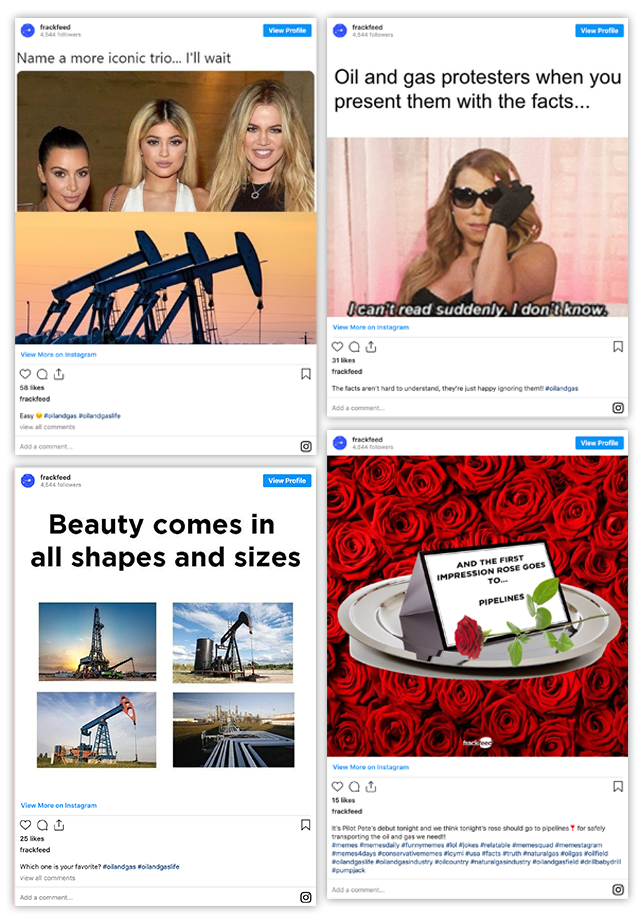

As I dug deeper into Texans for Natural Gas, I found other examples of the group courting women. Some were on FrackFeed, the group’s jokey, cringey meme feed with its own website and an Instagram account of more than 4,000 followers:

On other platforms, Texans for Natural Gas posts memes that downplay the amount of methane that leeches from natural gas operations set against feminine backdrops of fields of flowers and sunsets:

I asked Texans for Natural Gas why it was particularly interested in reaching women, but neither the group nor its sponsors got back to me. It’s worth noting that over the last few years, the oil and gas industry has been plagued by sexual harassment suits. Employees accused the company Anadarko, acquired last year by Occidental Petroleum, of having “a culture of treating women as sexual playthings who are present at work merely for men’s sexual gratification.” And one female oil worker filed a $100 million suit against the oilfield services company Schlumberger in June, alleging, “Women who work on oil rigs are sexually assaulted, sexually harassed, groped, leered at, and treated as sexual objects by their male colleagues.”

The women-centered messaging could be a clumsy attempt to distract from those scandals. More likely, though, Texans for Natural Gas is simply hoping to convince the public that women are creating a political demand for a future with natural gas. Other industries have employed this strategy, too: As I reported this year, gas-powered utilities have spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on marketing campaigns that hire social media influencers to make cooking with gas stoves seem cool and trendy, despite the indoor air pollution they create. These industries have reason to be worried: Republican and Democratic women tend to care more about the environment and climate change, polling shows. The Guardian has reported on internal polling by the Partnership for Energy Progress, a northwestern coalition of gas utilities and natural gas companies, identifies women between ages 35 and 54 who own homes and have college degrees as “flight risks,” meaning they could soon stop supporting gas stoves and fossil fuels in buildings for environmental reasons.

Indeed, the claim that natural gas is environmentally friendly is disingenuous. Though it was once seen as the lesser of two evils compared to coal’s high carbon pollution, we’ve learned over the past decade that natural gas has come at a high cost. We’ve vastly undercounted the amount of methane escaping from these operations by as much as 60 percent, reporting from the Environmental Defense Fund shows, as the industry has been largely left to regulate itself. Texans for Natural Gas, run by oil and gas companies, has an interest in downplaying these risks to keep the status quo of a self-regulated industry.

That the gas industry is peddling dubious claims to women is part of a broader pattern: From alternative health products to far-right conspiracy theories, women have emerged as a prime target for purveyors of disinformation. Indeed, Hempel told me that what bothered her most about the incident was that her photo was being used under a false pretense to spread spurious claims. “How many other places am I taking for granted that somebody is who they say they are, and trusting that an organization is representing that interest?” she said. “How many things do I take for granted when I am gathering information in my professional practice and in my daily life that are total hoaxes?”