People wait in line to fill propane tanks in Houston after widespread blackouts.David J. Phillip, AP

One of the many reasons millions of Texans were stranded without power in freezing temperatures this week was a fairly common, but faulty, assumption that the future will look a lot like the past. Even without climate change, this approach doesn’t work, because there is always the small chance of a worst-case scenario. But with climate change, betting on a future that resembles what we’re used to is downright irresponsible. The United States, generally, does a poor job planning for the extremes, especially as those extremes become more likely because of climate change.

This was certainly a factor in Texas, even if scientists are still hammering out the effect climate change has on unusually bad wintry weather. The Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), the nonprofit that operates Texas’ independent power grid system, did not see a deep freeze of this scale coming, using the average of past winters as a benchmark. Umair Irfan at Vox highlighted a quote from an ERCOT report forecasting winter energy demand and supply in Texas: “We studied a range of potential risks under both normal and extreme conditions, and believe there is sufficient generation to adequately serve our customers.” However, as demand for electricity went soaring, more than 30,000 megawatts of power went offline, already twice the level ERCOT planned for in its most extreme scenario planning.

It is possible to plan better, as Jesse Jenkins, a grid expert at Princeton University, wrote in a New York Times op-ed this week. Jenkins highlighted the preparations Texas could have taken:

Pipelines can be buried deeper to insulate against the ground’s cold surface. When gas supplies are disrupted, dual fuel power plants can switch from gas to petroleum stored on site. Wind turbines can be equipped with heaters to keep blades free of ice. Sensors, valves and coolant intakes can be protected against freezing. Long-distance power lines can connect to other regions’ power systems and draw from their supplies during times of need. All of this is possible but costly.

Jenkins argued, “We have to use foresight, not hindsight, to identify the kinds of crises that we wish to protect against.”

While Texas is unique for its independent, in-state power grid, which puts it at a disadvantage in handling extremes because it has fewer options to turn to when plants are taken offline, the state is not unique in using hindsight as its guide to prepare for future crises.

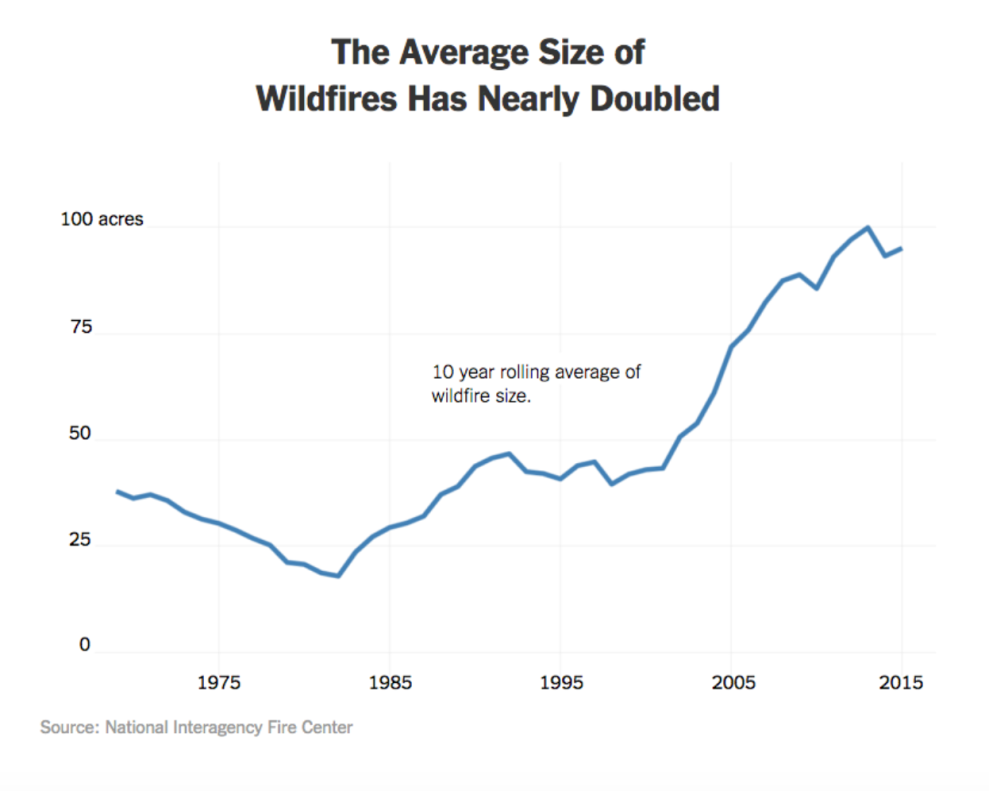

The federal government plans its budget for wildfire seasons using a rolling average of the past 10-years of wildfires. With wildfires more likely to spark and burn more widely with drier conditions and soaring temperatures out west, this approach fails to take into account climate projections, and the result is cutting into the rest of the Forest Service’s budget. As a 2015 report from the Department of Agriculture on the rising costs of wildfire suppression detailed:

Wildland fire suppression activities are currently funded entirely within the U.S. Forest Service budget, based on a 10-year rolling average. Using this model, the agency must average firefighting costs from the past 10 years to predict and request costs for the next year. When the average was stable, the agency was able to use this model to budget consistently for the annual costs associated with wildland fire suppression. Over the last few decades, however, wildland fire suppression costs have increased as fire seasons have grown longer and the frequency, size, and severity of wildland fires has increased.

The National Flood Insurance program uses similarly bad logic, basing rates on outdated definitions for floodplains on the likelihood of 100-year floods, ignoring that these definitions no longer hold up as flooding becomes an annual threat.

Joe Scata, a climate attorney at Natural Resources Defense Council, explained last month how FEMA has not comprehensively updated its standards for building and land-use in flood-prone areas since the 1970s. And while Congress mandates FEMA include projections of sea level rise when it does update its flood maps, Scata writes, “FEMA has not included future conditions on any of the 8,000 maps the agency has updated since Congress imposed its mandate. That means communities are making development decisions based on the climate of the past, not the future.”

Texas is not helped by the denial that runs deep in its elected officials. But it’s clearly not just a Texas problem. The federal government, states, and cities still have a lot of work to do to recognize that the future threats will not look anything like what we’ve seen before.