Early last year in the Fox Hills neighborhood of Culver City, California, a man named Wilson Truong posted an item on the Nextdoor social media platform—where users can interact with their neighbors—warning that city leaders were considering stronger building codes that would discourage the use of natural gas in new homes and businesses. In a message titled “Culver City banning gas stoves?” he wrote, “First time I heard about it I thought it was bogus, but I received a newsletter from the city about public hearings to discuss it…Will it pass???!!! I used an electric stove but it never cooked as well as a gas stove so I ended up switching back.”

Truong’s post ignited a debate. One neighbor, Chris, defended electric induction stoves. “Easy to clean,” he wrote of these glass stovetops, which use a magnetic field to heat pans. Another neighbor, Laura, expressed skepticism. “No way,” she wrote. “I am staying with gas. I hope you can too.”

Unbeknownst to both, Truong wasn’t their neighbor at all, but an account manager for Imprenta Communications Group. Among the public relations firm’s clients was Californians for Balanced Energy Solutions, a front for the nation’s largest gas utility, SoCalGas, which aims to thwart state and local initiatives restricting the use of fossil fuels in new buildings. c4bes had tasked Imprenta with exploring how platforms such as Nextdoor could be used to engineer community support for natural gas. Imprenta assured me that Truong’s post was an isolated affair, but c4bes displays it alongside two other anonymous Nextdoor comments on its website as evidence of its advocacy in action.

Microtargeting Nextdoor groups is part of the newest front in the gas industry’s war to bolster public support for its product. For decades the American public was largely sold on the notion that “natural” gas was relatively clean, and when used in the kitchen, even classy. But that was before climate change moved from distant worry to proximate danger. Burning natural gas in commercial and residential buildings accounts for more than 10 percent of US emissions, so moving toward homes and apartments powered by wind and solar electricity instead could make a real dent. Gas stoves and ovens also produce far worse indoor air pollution than most people realize; running a gas stove and oven for just an hour can produce unsafe pollutant levels throughout your house all day. These concerns have prompted moves by 42 municipalities to phase out gas in new buildings. Washington state lawmakers intend to end all use of natural gas by 2050. California has passed aggressive standards, including a plan to reduce commercial and residential emissions to 60 percent of 1990 levels by 2030. During his campaign, President Biden called for stricter standards for appliances and new construction. Were more stringent federal rules to come to pass, it could motivate builders to ditch gas hookups for good.

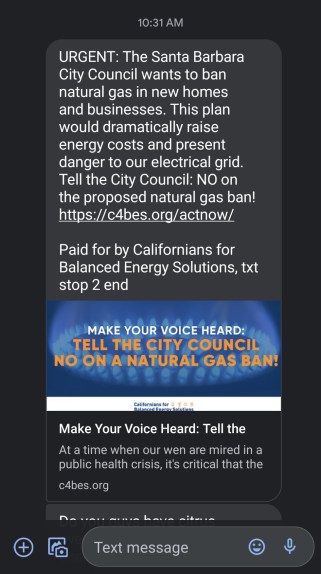

Gas utilities have responded to this existential threat to their livelihood by launching local anti-electrification campaigns. To ward off a municipal vote in San Luis Obispo, California, a union representing gas utility workers threatened to bus in “hundreds” of protesters during the pandemic with “no social distancing in place.” In Santa Barbara, residents have received robotexts warning that a gas ban would dramatically increase their bills. The Pacific Northwest group Partnership for Energy Progress, funded in part by Washington state’s largest gas utility, Puget Sound Energy, has spent at least $1 million opposing electrification mandates in Bellingham and Seattle, including $91,000 on bus ads showing a happy family cooking with gas next to the slogan “Reliable. Affordable. Natural Gas. Here for You.”

The industry group American Gas Association has a website dedicated to promoting cooking with gas.

The gas industry also has worked aggressively with legislatures in seven states to enact laws—at least 14 more have bills—that would prevent cities from passing cleaner building codes. This past spring, according to a HuffPost investigation, gas and construction interests managed to block cities from pushing for the stricter energy efficiency codes favored by local officials. In a potential blow to the Biden administration’s climate ambitions, two big trade groups convinced the International Code Council—the notoriously industry-friendly gatekeeper of default construction codes—to cut local officials out of the decision-making process entirely.

Beyond applying political pressure, the gas industry has identified a clever way to capture the public imagination. Surveys showed that most people had no preference for gas water heaters and furnaces over electric ones. So the gas companies found a different appliance to focus on. For decades, sleek industry campaigns have portrayed gas stoves—like granite countertops, farm sinks, and stainless-steel refrigerators—as a coveted symbol of class and sophistication, not to mention a selling point for builders and real estate agents.

The strategy has been remarkably successful in boosting sales of natural gas, but as the tides turn against fossil fuels, defending gas stoves has become a rear guard action. While stoves were once crucial to expanding the industry’s empire, now they are a last-ditch attempt to defend its shrinking borders.

Over the last hundred years, gas companies have engaged an all-out campaign to convince Americans that cooking with a gas flame is superior to using electric heat. At the same time, they’ve urged us not to think too hard—if at all—about what it means to combust a fossil fuel in our homes.

In the 1930s, the industry embraced the term “natural gas,” which gave the impression that its product was cleaner than any other fossil fuel: “The discovery of Natural Gas brought to man the greater and most efficient heating fuel which the world has ever known,” bragged one 1934 ad. “Justly is it called—nature’s perfect fuel.”

It was also during the 1930s that the industry first adopted the slogan “cooking with gas”; a gas executive saw to it that the phrase worked its way into Bob Hope bits and Disney cartoons. By the 1950s the industry was targeting housewives with star-studded commercials that featured matinee idols scheming about how to get their husbands to renovate their kitchens. In one 1964 newspaper advertisement from the Pennsylvania People’s Natural Gas Company, the star Marlene Dietrich professed, “Every recipe I give is closely related to cooking with gas. If forced, I can cook on an electric stove but it is not a happy union.” (Around the same time, General Electric waged an advertising campaign starring Ronald Reagan that depicted an all-electric house as a Jetsons-like future.) During the 1980s, the gas industry debuted a cringeworthy rap: “I cook with gas cause the cost is much less / Than ’lectricity. Do you want to take a guess?” and “I cook with gas cause broiling’s so clean / The flame consumes the smoke and grease.”

The sales pitches worked. The prevalence of gas stoves in new single-family American homes climbed from less than 30 percent during the 1970s to about 50 percent in 2019. In some of the most populous cities—particularly in California, New York, and Illinois—well over 70 percent of homes now rely on gas for cooking. According to the American Gas Association, residences, including apartments, make up 68 percent of the industry’s revenue.

Beginning in the 1990s, the industry faced a new challenge: mounting evidence that burning gas indoors can contribute to serious health problems. Gas stoves emit a host of dangerous pollutants, including particulate matter, formaldehyde, carbon monoxide, and nitrogen oxides. One 2014 simulation by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory found that cooking with gas for one hour without ventilation adds up to 3,000 parts per billion of carbon monoxide to the air—raising indoor concentrations by up to 30 percent in the average home. Carbon monoxide can kill; it binds tightly to the hemoglobin molecules in your blood so they can no longer carry oxygen. What’s more, new research shows that the typical home carbon monoxide alarms often fail to detect potentially dangerous levels of the gas. Nitrogen oxides, which are not regulated indoors, have been linked to an increased risk of heart attack, along with asthma and other respiratory diseases. Homes with gas stoves have anywhere between 50 and 400 percent higher concentrations of nitrogen dioxide than homes without, according to EPA research. Children are at especially high risk from nitrogen oxides, according to a study by UCLA Fielding School of Public Health commissioned by the Sierra Club. The paper included a meta-analysis of existing epidemiological studies, one of which estimated that kids in homes with gas stoves are 42 percent more likely to have asthma than children whose families use electric.

Shelly Miller, a University of Colorado, Boulder, environmental engineer who has studied indoor air quality for decades, explains that when a stove burns natural gas—just as when a car burns gasoline—that combustion reaction oxidizes molecules in the air to create nitrogen oxides, which can make us sick. “Cooking,” she says, “is the No. 1 way you’re polluting your home. It is causing respiratory and cardiovascular health problems; it can exacerbate flu and asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in children.” Between the stove emissions and other household chemicals, “you’re basically living in this toxic soup.”

In the face of mounting health concerns, the industry has taken an approach right out of the tobacco playbook, citing a lack of regulation by the Consumer Product Safety Commission and the EPA as evidence of why the public shouldn’t be concerned. But the EPA has never said gas stoves are safe. In 2016, the agency linked short- and long-term nitrogen dioxide exposure to respiratory problems like asthma. The UCLA study found that indoor NO2 emissions from running a stove alone can sometimes cause levels that the EPA would consider unacceptable outdoors, and running an oven at the same time makes things even worse. Indeed, the data shows that California’s buildings emit more nitrogen oxides than power plants, and only slightly less than cars.

The gas industry claims that proper ventilation can take care of any combustion fumes. Yet even among families who are aware of the potential health effects, many cannot afford to install a sufficiently powerful hood vent, and there’s certainly no regulation requiring it. Indeed, most stove fans do little more than move the polluted air about. Because of dated building codes and an unregulated market, low-income Americans, many of whom are renters, have to put up with invisible combustion byproducts in cramped living spaces.

Last year, I published an article that exposed how trade groups representing gas utilities hired social media influencers to convince millennials and Gen Xers that gas stoves are the cool and superior way to cook. In the Instagram posts I reviewed, none of the influencers appeared to have fume hoods over their stoves, or even mentioned ventilation. I knew I had gotten the industry’s attention when many of the posts were suddenly deleted, and I started receiving long, unsolicited emails from industry consultants.

Around that time, I came across a trove of emails obtained by the fossil fuel watchdog Climate Investigations Center. According to the emails, representatives from the PR firm Porter Novelli had reached out to one of its clients, American Public Gas Association (APGA), which then emailed gas executives at several utilities to ask whether Porter Novelli’s social influence campaign on behalf of APGA should be paused in light of the backlash from my piece. “They should not stop for even 1 hour,” replied utility executive Sue Kristjansson, an industry veteran. “If they are saying that we are paying influencers to gush over gas stoves so be it. Of course we are and maybe we should pay them to gush more?”

The emails showed the executives debating their next move: Some thought they should tell the influencers to emphasize proper ventilation. Others worried that giving even an inch to their critics would be admitting defeat. “If we wait to promote natural gas stoves until we have scientific data that they are not causing any air quality issues we’ll be done,” wrote Kristjansson, who is now president of Berkshire Gas, a utility in Massachusetts. When I reached out to Kristjansson for comment, a Berkshire spokesperson sent me a statement, repeating familiar claims: “The science around the safe use of natural gas for cooking is clear: there are no documented risks to respiratory health from natural gas stoves from the regulatory and advisory agencies and organizations responsible for protecting residential consumer health and safety.”

Yet Kristjansson’s hard-line approach seems to be losing favor. Take Kate Arends—the founder of Wit and Delight, a polished lifestyle website for “designing a life well-lived”—whose Instagram account has more than 300,000 followers. Arends’ brand fits perfectly with the affluent female demographic the industry hopes to target—indeed, at least one of her posts is sponsored by APGA.

A week after my story ran, Porter Novelli contacted APGA again, this time on behalf of Arends, seeking the group’s guidance on how best to communicate on “issues related to ventilation.” Arends wanted to make sure any health and safety information she shared was accurate. Months passed—by fall I had not seen any more sponsored posts from Arends and wondered whether she had dropped the sponsorship.

Then, late last October, she ran a post sponsored by Natural Gas Genius, an APGA campaign: “An Exercise in Candlemaking and the Comforts of a Roaring Fire.” In a 600-word post festooned with photos of her exquisitely decorated home, Arends explained her decision to replace her wood-burning fireplace with a natural gas model and extolled the wonders of her gas stove. Tellingly, her post included a note that shows how the industry has grown savvier on the delicate issue of air quality. “If natural gas is the right choice for your family,” she wrote, “ventilation and air quality are the things to keep top of mind.” It was the first time I had ever seen an influencer acknowledge the need for ventilation.

So far, every city that has tried to pass cleaner building codes has faced an onslaught of gas industry attacks. Sierra Club’s Western regional director, Evan Gillespie, remembers how quickly SoCalGas reacted two years ago when an obscure California agency, the South Coast Air Quality Management District, decided to discuss the full emissions impact from gas appliances. Gas groups sent one representative to a district meeting, three to the next one, and seven to the next, accounting for a full one-third of that meeting’s attendance. Leah Stokes, a political scientist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and author of a book on utility astroturfing, described to me the unsettling experience of seeing how quickly the SoCalGas-aligned C4BES swamped the Santa Barbara City Council after sending residents texts and emails warning of higher electricity rates and gas stove bans.

But the tables may be turning. In November, the powerful environmental regulators at the California Air Resources Board issued an unequivocal statement proclaiming that gas stoves cause indoor air pollution. The announcement, a possible gamechanger for cities on the fence about electrification, calls for much stricter ventilation standards for all household appliances. It was the first time any major public agency has recommended policy changes to reflect the science of stoves and indoor pollution.

Environmentalists say the move away from gas is as inevitable as the demise of coal. It’s not a matter of if buildings go electric, but when. The California Energy Commission plans to incorporate subsidies for electric home heating and hot water in its next update to the state’s building code; some experts anticipate that it may even ban gas in new construction starting in 2026. That prospect has the industry scrambling: If California’s most populous cities—which account for 8 percent of construction-related greenhouse gases—phase out gas-fired structures, other states will likely follow suit.

“If we’re able to get gas bans in new buildings, then these gas companies are losing their growth, they’re losing their new market share, and they’re going to start shrinking,” says Stokes. “That sort of downward spiral becomes very problematic, because then investors start to think this isn’t a good company to invest in. The fights that are playing out in California and New York are really bellwethers for the gas industry overall.”

The industry doesn’t want too many dominos to fall, including in places like Culver City, where Truong made his pro-gas Nextdoor post. Reached by phone, Imprenta vice president Joe Zago distanced his company from the campaign. Zago told me that C4BES had tasked Imprenta with finding a sympathetic resident of the middle-class Fox Hills neighborhood to post a statement supporting its position, but Truong had acted independently: “He made this post on his own without direction or approval from anyone at Imprenta and without the knowledge of Imprenta or our client.” The firm’s contract with C4BES—now the subject of a state inquiry into the improper use of ratepayer dollars on anti-electrification campaigns—expired in February 2020, Zago added, and Imprenta’s work with C4BES was “fairly limited in scope.”

Imprenta isn’t the only firm backing away from gas companies. In November, Porter Novelli announced it would drop the American Public Gas Association and cease participation in the Natural Gas Genius campaign. “We have determined our work with the American Public Gas Association is incongruous with our increased focus and priority on addressing climate justice,” Porter Novelli executive Maggie Graham explained to the New Yorker.

The mounting criticism of natural gas has put the industry on the defensive. After a version of this story ran online, the Independent Petroleum Association of America penned a response on its public outreach website: “The article misrepresents why natural gas became and remains the dominant energy source for homeowners, overlooking the crucial fact that the resource has been delivering the most affordable energy for decades,” and the industry “is working to address individuals’ primary need for affordability and their climate concerns, too.”

Environmentalists see the defection of the PR firms as evidence of a shift in public sentiment. Consumers are beginning to realize, “I’m burning fossil fuels with an open flame in my house, and it’s contributing to asthma my kid has; it’s harming my mom, my dad, and my grandparents,” says the Sierra Club’s Gillespie. “I think people’s perception of what it means to have a gas stove changes pretty quickly.”

The industry has spent a century convincing Americans to fall in love with gas stoves, but as the public begins to fully understand the risks of what used to be its favorite appliance, Gillespie predicts, “what was long seen as this great strength of the industry is actually their greatest weakness.”

Images from left: The National Archives/Getty, GraphicaArtis/Getty

This article has been revised and updated after a print version was featured in our July/August 2021 issue.