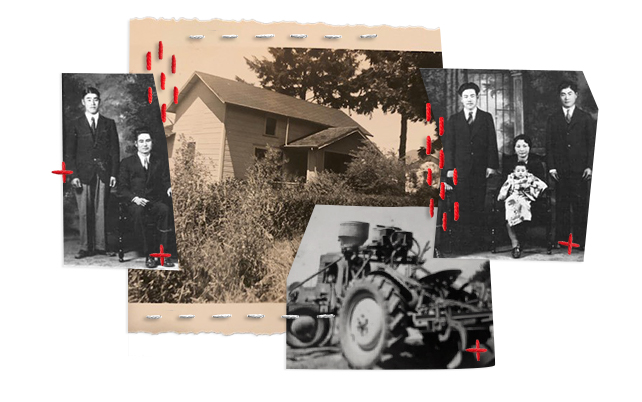

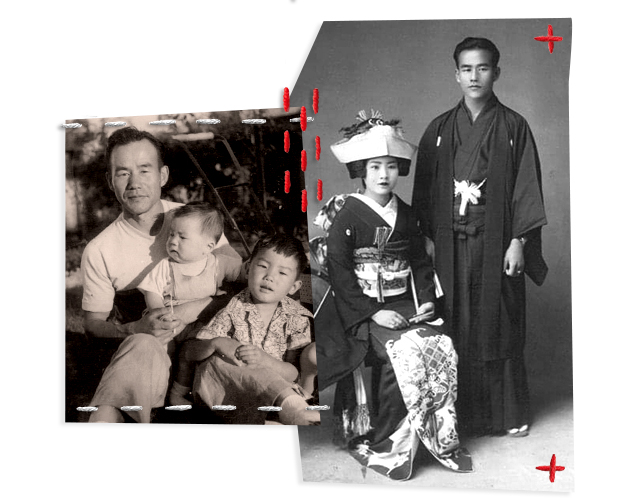

West of Sacramento, in a rural community called Broderick, my grandfather Shigeki, and his brothers, Yoshimi, Tadao, and Hideo, were farmers. We were told the land they worked was leased by my great-uncle’s in-laws, the Abe family, who were glad to have the labor of the young and fit Murai brothers. They were quiet men, industrious and skilled. The work was difficult and they must have savored the occasional breeze off of the Sacramento River. The Murai brothers were of the Nisei generation, born in the United States to Japanese immigrants (Issei), but my grandfather was raised and educated mostly in Japan before he returned to work this land, to earn a living, to build a life. His story was not unusual. In 1940, 45 percent of employed Japanese people on the Pacific Coast worked in agriculture. Californian Issei and Nisei farmers dominated the wholesale and retail fruit and vegetable markets in the state.

For more articles read aloud: download the Audm iPhone app.

I know very little about this farm. My family left it behind for good in 1942, when my grandfather was in the Army and his brothers were incarcerated along with thousands of other Japanese Americans during World War II. The land never belonged to our family, but the house they left behind had been built lovingly with the help of the Japanese community in the area after a fire had destroyed their previous home. When they left home, the house was still relatively new, and they had been excited for the memories that would be made there. But many of the children they imagined raising in that house would instead grow up in incarceration camps.

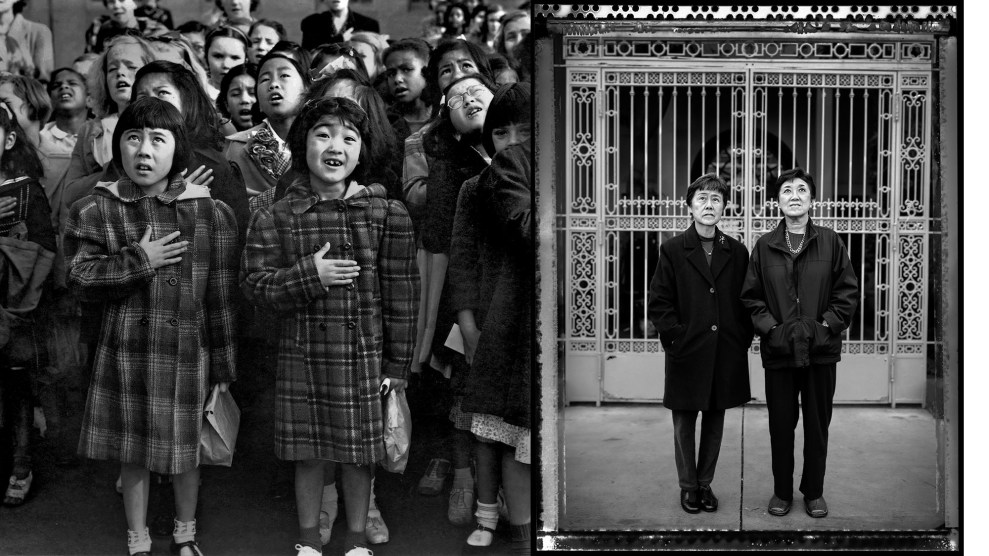

This week marks the 80th anniversary of President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, which authorized the secretary of war to round up as many as 126,000 Japanese American men, women, and children who lived on the Pacific Coast, after the Pearl Harbor attack stoked fears about Japanese American loyalty. For many years, this era was referred to as Japanese internment. But that term is inadequate, since it describes the imprisonment of foreign nationals, and over half of those detained were American citizens.

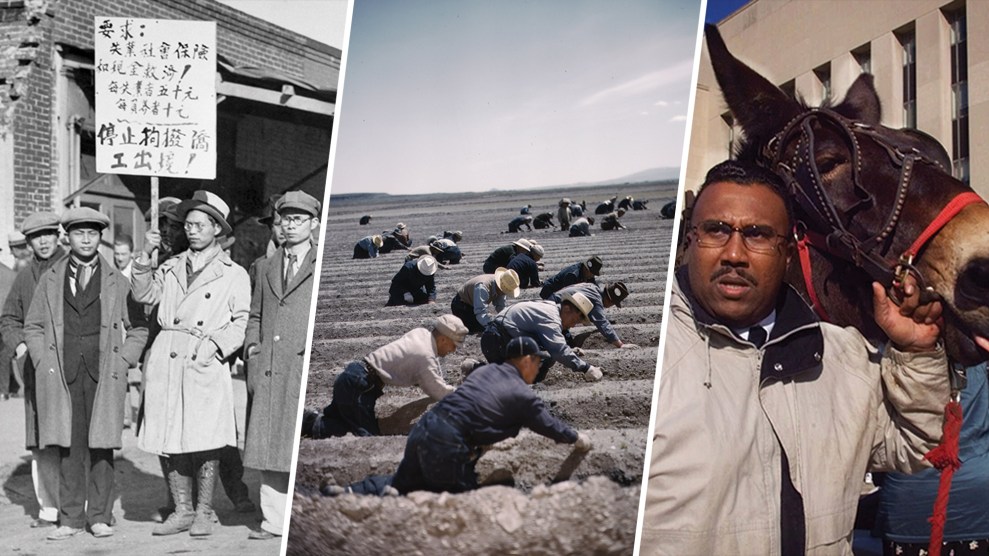

The anti-Japanese sentiment that allowed for such a drastic action to take place did not spring up suddenly after Pearl Harbor, but had been simmering for decades, stoked by white labor and business groups resentful of Japanese workers and farmers. Japanese Americans who were forced off their land lost property worth an estimated $3.7 billion in today’s dollars, and $7.7 billion worth of income.

But not all losses are quantifiable, even in estimates. How can we count the communities dispersed, the culture disappeared? In the 80 years since, there’s been another loss: the memories of survivors of this forced removal. Some have merely faded, but many memories have been locked away as families decided it would be best not to talk about them. To move on. To insist it wasn’t that bad. More pressing are the memories that are simply gone. There’s an urgency to collect these stories before there are no more living survivors, a day that is approaching quickly.

In my family, the memories are already mostly lost. My grandfather, my great uncles, and their wives have all passed away. My father, my most direct connection to this history and to the Japanese half of my ancestry, also died when I was 2 years old. I never got to speak with him about his relationship with his father, or what he might’ve shared about the farm, his time in the Army, or his family’s incarceration. To avoid losing these memories completely, I reached out to my father’s brother, Uncle Stan, and some of their cousins—some who were very young when their families were detained, others born after. I spoke with them hoping that there’s still a story to inherit.

The disappearance of my family’s farm can be traced back even further than the executive order that forced them to leave. Japanese immigrants had started to come to California in the early 20th century, and the backlash started immediately, in the same mold of the anti-Chinese bias that was already prevalent.

In May 1900, the San Francisco Labor Council held a meeting to address the tensions. White laborers were fearful for their jobs, but San Francisco Mayor James Duval Phelan emphasized that Japanese immigration was not just a labor issue. It was an existential threat, on par with the surge that led to the fall of Rome. He stated that immigration was “not a labor question, nor a local one, but an American question involving the existence of our Republic.” In a speech applauded by the attendees, Mayor Phelan said he believed that Japanese “aren’t the stuff of which American citizens can be made.”

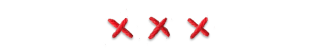

Though the federal government was hesitant to ban Japanese immigration as it had Chinese immigration because of Japan’s status as a rising global power, pressure from California farm and labor groups led it to strike the informal Gentlemen’s Agreement with Japan in 1907. The Japanese government agreed to stop issuing passports to laborers. The Issei already in California started to send for wives from Japan.

To deal with the Japanese families putting down roots and to appease white farm lobby and labor groups, the California legislature passed the Alien Land Law of 1913, barring noncitizens from owning land or long-term leases. When this law proved largely ineffective due to its many loopholes, business and labor organizations and white farmers led an anti-Japanese movement to pass a more prohibitive, if again somewhat ineffective, law in 1920, when California Issei produced 10 percent of the total market value of crops in California. Cecilia Tsu, a historian at the University of California, Davis, says this second law was particularly important because it “reflected more widespread public opinion that was brewing about the danger of Japanese immigrants settling as families.” She points out that white farmers feared a growing population of birthright citizens, the Nisei, who could not be constitutionally barred from owning land.

And so, in the 1940s, my family’s farm was leased to them by someone who could legally own the land. Their last name was Todhunter.

Today, Broderick is part of West Sacramento. Todhunter Avenue runs from the busy Sacramento Avenue all the way to the banks of the Sacramento River. It’s a quiet road, lined mostly by single family homes. There’s a church. A school. A large park. I haven’t been able to locate any records to tell me where the farm was, but as I click through the photos of the street named for its once legal owner, I try to imagine it here.

Follow the Sacramento River southeast, and you reach Old Sacramento on the riverbank. Between 3rd and 4th streets, L and Capitol, there is a vacant lot. In the 1930s, this was once Japan Alley, the heart of a bustling and thriving Japantown. Here, the community gathered to shop, eat, and celebrate the Japanese Buddhist festival Obon. I can picture my grandfather, who I’ve been told was the most outgoing of the Murai brothers, telling jokes to the Japanese shopkeepers or teasing the kids hanging outside the pharmacy on 3rd Street.

I picture him on these streets, perhaps saying his goodbyes to the crowd my uncle says accompanied him to the train station when he was drafted into the military three months before Pearl Harbor. Eventually, my grandfather would graduate from the Military Intelligence Service Language School at Camp Savage in Minnesota. But that day at the station, my uncle says my grandfather didn’t entirely understand what was happening to him as dozens of family members and friends waved farewell, cheering and yelling “banzai” as he pulled away from the station.

Seven months later, those same family members boarded trains too, some to Arizona, and others to Colorado. They sold most of their belongings, not knowing when they would be allowed to return. Hideo’s daughter Doris Yamamoto was about 5 when they were forcibly removed, and she remembers that a trunk stored a beautiful little white outfit that her mother, who was a talented seamstress, had stitched for her. She was distraught when the trunk was lost or taken before they got to camp in Poston, Arizona. Nobody had been at the station to wave goodbye.

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt issued EO 9066. The order allowed the secretary of war to “prescribe military areas in such places…from which any or all persons may be excluded.” The order did not specifically name the Japanese, but they alone were targeted supposedly out of military necessity for the safety of the nation.

The Japanese Americans stood to lose everything, and in their absence, there was so much to gain.

Shortly after the Japanese army attacked Pearl Harbor, Austin Anson, the managing secretary of the Salinas Vegetable Grower-Shipper Association, left for Washington, DC. His mission was to urge Federal authorities to incarcerate all the Japanese people in the area. Anson spoke to the War and Navy departments and any congressman he could get to listen, emphasizing the potential danger Japanese saboteurs posed on the Pacific Coast. It may seem odd that a representative for a farming group would talk about military strategy with political leaders, but Anson wasn’t afraid to say the quiet part out loud.

“We’re charged with wanting to get rid of the Japs for selfish reasons,” Anson told the Saturday Evening Post in May 1942. “We might as well be honest. We do. It’s a question of whether the white man lives on the Pacific Coast or the brown men. They came into this valley to work, they stayed to take over…And we don’t want them back when the war ends, either.”

The forced removal of tens of thousands of American citizens was later investigated in the 1980s by a commission authorized by Congress and President Jimmy Carter. They found that the incarceration “was not justified by military necessity,” but instead shaped by “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” Though the latter two factors may have been a product of that specific moment in time, the prejudice against the Japanese people was a direct product of the decades of work by anti-Japanese labor and business groups. The Issei and Nisei were successful at what they did, despite the legal barriers they’d faced, and it terrified the agricultural establishment, and that fear was an essential component in instigating an incarceration that was otherwise unjustified.

At the same time Anson was in DC advocating the incarceration, Japanese families at home on the Pacific Coast were destroying their memories. As FBI agents began taking away important community members for questioning, families ripped up photographs and smashed mementos that could link them to Japan in an effort to stay safe. I lost heirlooms I don’t even know about. But the exclusion order went up anyway, and it did not discriminate between those Japanese people who were loyal to the US and those who were not.

“The Japanese were never Americans in California,” Dr. C. L. Dedrick, a sociologist and Census Bureau expert with one of the federal agencies tasked with implementing forced removal in 1942 told the Saturday Evening Post. “Now, when they are dispersed, they may ultimately become absorbed in American life, not by intermarriage, but through losing their concentrated identity. This may be their great chance to become Americans.”

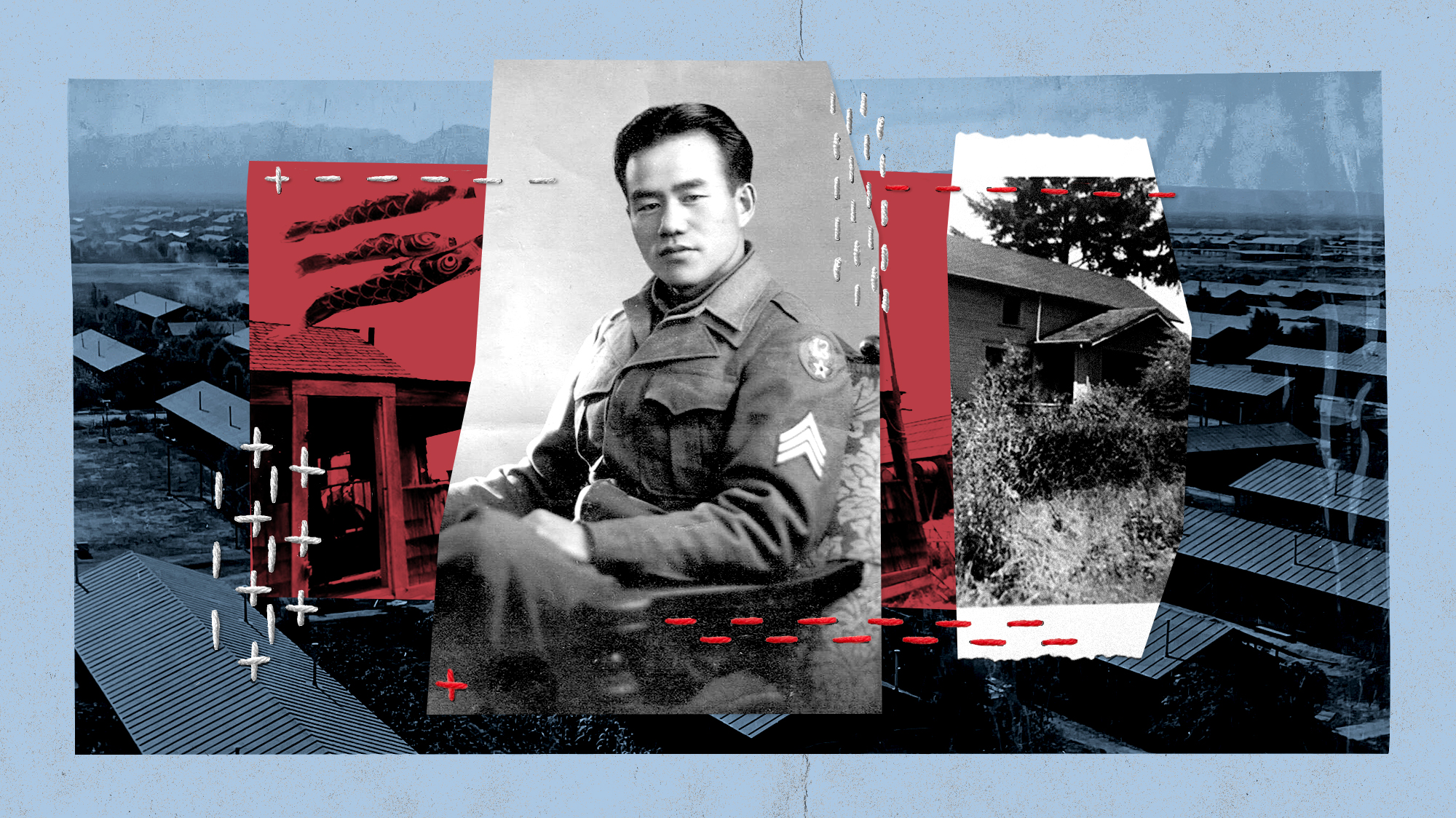

At the same time he was “never an American,” my grandfather was a “human secret weapon.” As a Nisei linguist in the Pacific, he screened the mail of Japanese POWs, including that of General Tojo Hideki. In 2010, Congress passed a bill honoring Nisei soldiers, including the Military Intelligence Service, with the congressional gold medal. This recognition came five years after my grandfather died, and cannot change the mixed emotions my uncle said his father had about his service while he was alive.

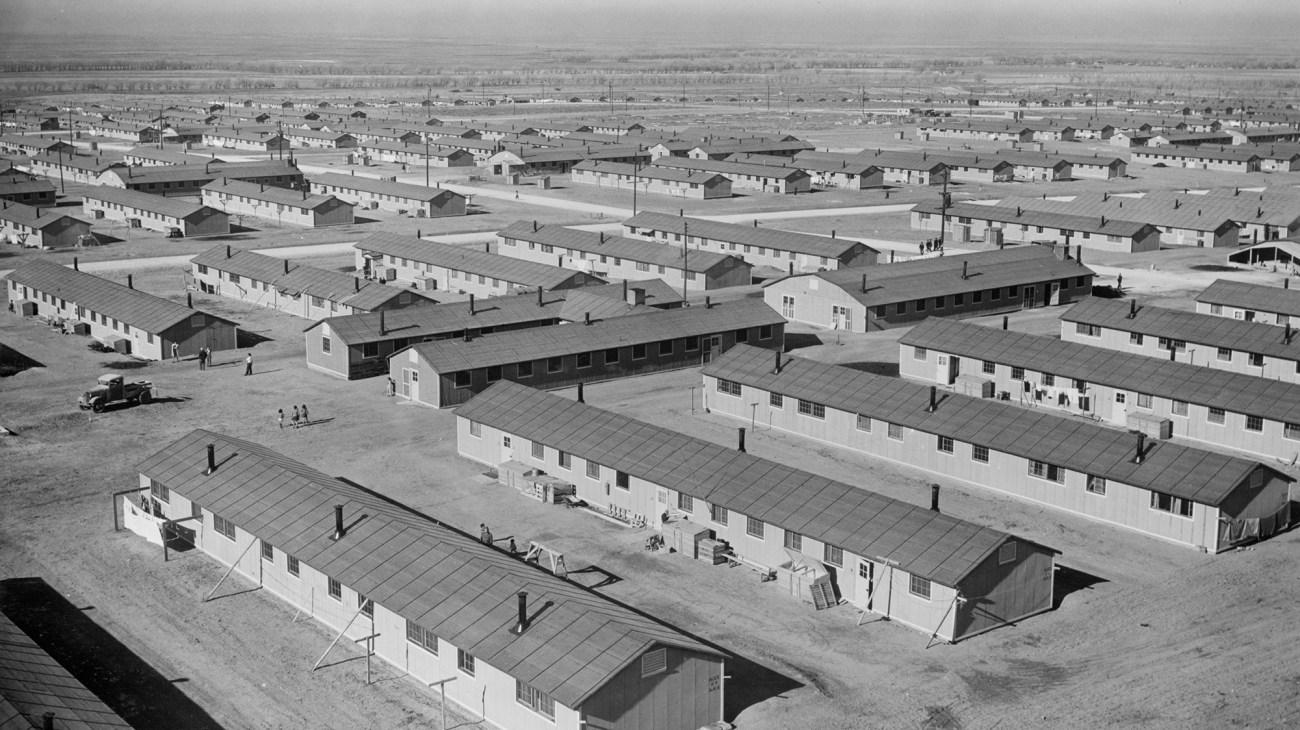

At some point during the war, my grandfather was able to visit some of his family at their camp in Granada, Colorado. He was startled when the train stopped for him in what felt like the middle of nowhere. A truck took him to the Amache camp where his family members were detained. In the only photo I have from his visit, he smiles next to his sister-in-law Masaye. But my uncle tells me the experience shocked my grandfather.

Panorama of Granada Relocation Center, Amache, Colorado, showing in the foreground a typical barracks unit consisting of 12 six-room apartment barrack buildings, a recreation hall, laundry and bathhouse, and the mess hall, constructed by Army Engineers.

United States War Relocation Authority/Library of Congress

My grandfather remained in the Army until at least 1947, a year after the last incarceration camp closed in March 1946. The rest of the Murais were a bit scattered. During their time in the camp, the Todhunter family, their landlord, sold the property in Broderick where they had once maintained their farm, and sent them a sum for the house they’d built on the land.

Hideo’s family ended up in Cleveland, Ohio, where they were some of the only Japanese people because his daughter needed to be in a hospital there. Yoshimi’s family remained in Colorado for a few years before returning to Sacramento, but he passed away not long after the war. Tadao moved around with his family frequently as he worked different farming jobs, even leasing his own farm for a while before eventually settling back in California.

Other Japanese Americans from the area returned to Sacramento immediately. In their absence, Korean, Chinese, Mexican, Portuguese, and Black communities had moved in. Japanese leaders worked hard to rebuild a flourishing Japantown within this new diverse community, and by and large were successful. The community thrived despite what was lost. Their return, however, was never really welcome.

The white community and city government viewed Japantown and the surrounding multiethnic West End as a “slum area,” a major PR problem in part because the West End was the gateway to Sacramento from San Francisco. A redevelopment plan called the Capitol Mall project was introduced in 1954 and eventually implemented despite protests from the Japanese community. Fifteen square blocks and half a century of history were demolished; 350 businesses and 92 percent of the population were displaced.

Today, where Japantown and the West End once stood, there are 29 Class A office buildings, luxury apartments, and parking garages. As for the farmers, the congressional commission studying the incarceration found that those “who had most before the war, also lost most.” Many farmers lacked the necessary funds to start over, and so took whatever jobs they could. Many, like my grandfather, were gardeners for the rest of their lives.

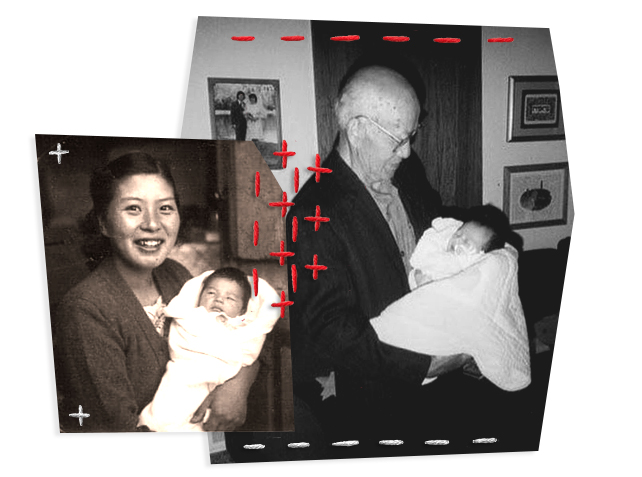

The details are murky of when and how my grandfather Shigeki eventually returned to California with his bride, a Japanese woman from his hometown, named Chizuko, for whom I would eventually be middle-named. Chizuko was from Iwakuni, and she witnessed the flash and the mushroom cloud of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima on her way to work. When she died at age 59 of an extremely aggressive and painful cancer, my family wondered if her proximity to the bomb resulted in the disease. I never met her, but when I was born, Shigeki held me wrapped in a tiny pink quilt she had stitched for my older sister.

For most of his life, Shigeki didn’t talk about the war or the farm before it. The same seems to be true of his brothers, and of many in the Japanese community. When my family does talk about it, they place a positive spin on the experience, or share funny anecdotes. Ken tells me that his mother, who smiled in the photo with my grandfather when he visited her at camp, only ever spoke about the silver linings of her time there: a break from work, afternoons with friends, an opportunity to enjoy her newlywed life. Doris says mostly the same, that she remembers very few of the details, and never spoke about camp with her family once they left. But the longer we talk, the more she recalls the heat of the Arizona desert, the happy memories of playing outside tangled up in recollections of the armed guards who towered above.

In 1980, the federal government approved the creation of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians to study EO 9066 and incarceration. The resulting 1983 report discussed the Japanese American community’s coping mechanisms. Dr. Tetsuden Kashima, in his testimony to the CWRIC, called the behavior “a social amnesia…a group phenomenon in which attempts are made to suppress feelings and memories of particular moments or extended time periods…a conscious effort…to cover up less than pleasant memories.”

The report, which also included the testimony of more than 500 detainees, was the result of the tireless work of Japanese American activists. Their continued organizing, along with the commission’s findings, led to the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, one of the only times in American history when the government offered reparations and apologies for its actions against a minority group. The Civil Liberties Act granted $20,000 of redress to all living survivors of incarceration camps. Perhaps more important than the money, those checks came with a formal letter of apology from President George H.W. Bush.

But the Japanese community’s feelings about the commission and redress are often complicated. When Tadao’s daughter Molly Nakaji speaks about the redress, she reflects mostly about how for her parents and so many others, it was too little too late, as they had passed away before they were able to receive the money or the apology. Lisa Doi, a community organizer with Tsuru for Solidarity, an organization comprising Japanese American social justice advocates and allies, pointed out that the commission’s framing of incarceration as a result of “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership,” “isolates the incarceration to an anomaly” rather than being “part of a much longer history of racial violence and mass incarceration in the United States.”

But she says there is still value in the government acknowledging its wrongdoing. “It’s perhaps an imperfect piece of legislation,” Doi says, but “it also serves as a reminder of what the government alongside communities is capable of doing to begin a process of repair.” Tsuru for Solidarity, motivated by the history of Japanese incarceration, works to end detention sites for all types of communities, with a focus on immigrants and refugees. Alongside groups like Nikkei Progressives and Nikkei for Civil Rights & Redress, Tsuru is now organizing to collect testimonies from the Japanese American community in support of HR40, federal legislation that would create a study commission similar to the CSRIC for African American reparations.

Though redress was a huge victory for the community, it did not signal the end of a trauma that has impacted even the generations that were never detained. Diana Emiko Tsuchida is the creator of an oral history project attempting to continue these conversations and understandings called Tessaku, named for a magazine that had been published by those incarcerated at Tule Lake in California. Her grandfather Tamotsu Tsuchida was, as she puts it, “quite a resistor in camp,” and was active in the fight for redress, eventually giving his own testimony to the commission.

To her family, the apology letter was “the thing that they needed to let go of the guilt that they felt for being Japanese.” Diana’s grandfather died only a few years after receiving his $20,000. After a life of resisting, speaking out, and refusing to forget, he used the money to pay for part of his care in a nursing home. “I wish my grandfather knew that someone was going to care about what he went through,” Tsuchida tells me. She funds the oral history project with her own finances, supplemented with support from Patreon. She makes the stories available online, but she has ambitions of creating an exhibit or a podcast in the future. “I feel like the best way I can honor what he went through is to continue the project,” she says.

Tessaku is not the only project aiming to document these histories. Walk the Farm was an organization started by Japanese American farmers to raise funds for Japanese farmers affected by the 2011 tsunami. Since then, the group has begun to collect the stories of Issei and Nisei Farms, many of which were lost when families were forcibly removed. It has amassed nearly 90 stories and is aiming for 1,000. Glenn Tanaka, a farmer and organizer of Walk the Farm, says that his hope for the project is that it inspires a younger generation to talk to their family members about the incarceration and about their history before it’s too late.

“You know, we are the stewards of this history,” says Tsuchida as we discuss the fast-approaching day when there will be no more firsthand accounts. That is not a light burden to carry, particularly at a time when history is being actively whitewashed in schools. If we are to understand the incarceration not as an anomaly but instead as part of a clear history of anti-Japanese sentiment, and an even greater history of racial prejudice in the US, then we are forced to accept that the story doesn’t end with the camps closing, the survivors passing on, or the family farm disappearing.

I am a researcher and a fact-checker. The central question of most of my work is “How do you know that?” My job is to read everything a reporter writes and ask, How do you know, how do you know, how do you know? I don’t accept less than the whole answer.

I have tried to check the facts of my family’s lives. I confirm their years of education in Japan through their internment records. My grandfather’s enlistment from military records. I use the patches on his uniform to prove he was in the Air Force. That he was a sergeant.

But how do I confirm that he took a particular pride in the vegetables he grew alongside his brothers? What keepsakes they brought with them when they returned to the US from Japan? How do I tell if he sent his family letters at camp, wondering if they were being screened the same way he was screening the mail of Japanese soldiers?

My grandmother Chizuko desperately wanted grandchildren. My older brother and sister were born just 10 months before she died.

I can’t. Earlier this week, a librarian I have sought help from in researching this article emailed me. He said he found a listing for “Murai Bros.” in a 1941 Sacramento County rural directory; there, they are listed as farmers and property owners. I have pieced together this article from my family’s memories. One cousin’s 97-year-old uncle recalled the land owner “Todhunter.” I have tried to verify what I can. But I feel as if I am falling short. I wish I could tell the true story of my family. I wish I could lay out in a whole answer what happened to that farm, to my family, and to my grandfather. I can only guess. From the anecdotes I’ve heard, I project the funny, kind, and loving man my mother describes to me onto the oral histories I read, wishing so badly that I could read his words too.

When I spoke to Glenn Tanaka, he asked me to submit my family’s story to the Walk the Farm database. I told him that I’m afraid I don’t know enough about it. There are too many details missing, so much lost that I can’t confirm. But he tells me, “I’d like to have a story like that,” because our farm was real, too.