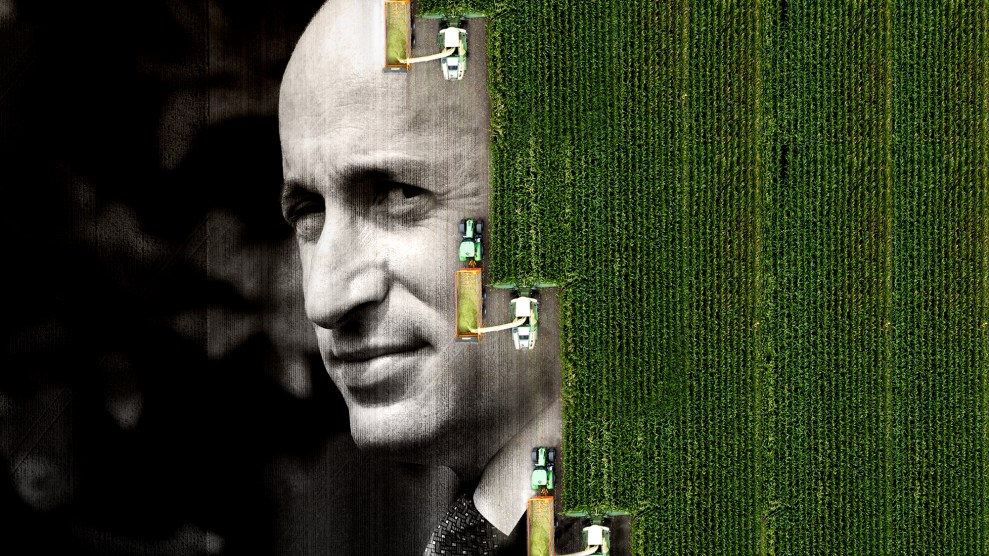

Remains from the Lincoln Heights neighborhood in Weed, California. Michael Kodas/Inside Climate News

This story was originally published by Inside Climate News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Weed, Calif.—On Sept. 2, DeAndre Thomas noticed the gusting wind at 5:30 in the morning. The 39-year-old had just finished his overnight shift at the veneer mill where he is a third-generation employee; his grandfather moved from Mississippi to Weed to work there in the mid-1900s.

Just after noon he lay down for a nap with his 11-year-old daughter, Jamila. He didn’t hear a boom around 12:45 from the mill property, now owned by Oregon-based Roseburg Forest Products, nor did he see flames ripping through the roof of one of its old warehouses.

By the time Thomas’s brother, who lives across the street with their parents, pounded on his door—You in there? Get out!—30 mile per hour winds were tossing embers onto Lincoln Heights, the neighborhood where they live just across the railroad tracks north of the mill.

Thomas opened the door to flames crackling on beige grass and crawling up a small tree. He and Jamila grabbed shoes and left just as a towering cedar a few feet from the home he shares with his wife and their two other children caught fire. “Daddy, I’m scared,” Jamila repeated through her tears.

A few blocks away, Stacey Green ran out of his home in socks into a neighborhood he couldn’t recognize, despite a lifetime there. He learned to ride his brown tricycle in Lincoln Heights, delivered The Weed Press to neighbors as a kid, and now serves as a city councilman and mayor pro tem. But thick, black smoke obscured everything. “I didn’t know where the ground was, but I was walking on it,” he recalls. “I kept asking myself: Am I dead? Am I dying?”

All he could hear was the wind and “fire whirling like an angry devil.”

Darin Quigley, Weed’s fire chief from 1990 to 2015, says only once during his tenure did smoldering ash in Shed 17 escape concrete barriers meant to separate the ash from the building’s flammable wood walls, but sprinklers “knocked it down,” he recalls.

On Sept. 2, Quigley could see Shed 17 implode in flames from the deck at the back of his house, and he knew the conditions were such that the fire was going to take off. “It’s so hot and dry these days with climate change. There are so many spot fires that just go,” he says. “If this had happened in 1990, the building would’ve burned down. But we would’ve held it there, not had 4,000 acres burned and two dead.”

DeAndre Thomas and his wife, Elizabeth, in the wreckage of their home in the Lincoln Heights neighborhood.

Michael Kodas

Without wind, there would be no Weed. The furious gusts that regularly rushed down the Cascade Mountains on California’s northern border could blow dry freshly cut lumber, leading Abner Weed to open his timber mill there in 1897. “Windy Weed,” the locals still say.

Paying $400 for 280 acres at the foot of Mount Shasta, about an hour south of Oregon, he established the Weed Lumber Company and the company-owned town of Weed, California, that would offer company housing, a company mercantile and conifer trees galore to feed his business.

When a Louisiana-based lumber company, Long Bell Lumber, bought the company in 1922, thousands of Black workers drove or train-hopped their way West, especially once word spread that wages in California were double what they were down South. Long Bell even paid the $89 train fare for workers coming from Louisiana, according to historical accounts.

While it’s well documented that millions of Black workers moved to cities like Oakland, Detroit and Chicago for factory and industrial work in the early to mid-20th century, an era known as the Great Migration, the story of Black people settling in California’s rural timber country, which is politically conservative and very white, is largely unknown.

Railroad tracks were often used to segregate housing when Black workers arrived. In Weed, homes for Black workers were built on land leased from Long Bell, and dubbed, “the Quarters.” The homes were smaller than white housing and without plumbing. As years passed, though, Black communities made these neighborhoods their own. Baptist churches were built and taverns with names like the “Harlem Club” opened; deep, lasting bonds formed.

“Every yard was our yard,” recalls 59-year-old Green, who hopped from house to house to play as a child in Weed’s historic Black neighborhood that in the ‘60s dropped “the Quarters” and was renamed Lincoln Heights.

It never felt like the “wrong side of town” to those who grew up there, though that’s how some in Weed saw it. Living next to the mill had its pitfalls, of course, like concerns about pollution, toxins and semi trucks belching through on their way to the mill, but on the plus side, there was a postcard-worthy view.

Bedroom and living room windows looked out at Mount Shasta, a majestic peak that’s noticeably transformed over generations. Residents no longer see a snow-capped mountain in the summer, rather it stands in shades of brown and deep pink. Wet, cold winters that once frosted mill workers in snow while out in the yards are now mild. The wind remains, though, typically from the south, often hitting Lincoln Heights head on.

The Black population in Weed has shrunk from 14 percent 50 years ago to 6 percent today. Still, Lincoln Heights held on as the only remaining Black enclave in California’s timber country, having endured with the lumber mill across the street as other mills closed and consolidated and the neighborhoods they supported emptied of residents. But, in the end, the wind and the mill that provided the opportunity from which Lincoln Heights rose also provoked the flames that destroyed it. It wasn’t the first time that the mill had menaced the neighborhood, nor were the hazards it presented always in the form of fire.

The remains of a shed that stored ash from a cogeneration plant used to generate electricity for the mill owned by Roseburg Forest Products.

Michael Kodas

For thousands of years, fire sustained a balanced ecosystem in Northern California; most native species in the region evolved with and adapted to regular wildfires. Neva Gibbons, deputy director of natural resources for the Karuk Tribe, says Siskiyou County, where Weed is located, once benefited from the tribe’s planned, managed burning.

But over the last 100 years, federal land managers largely stopped that practice, and prioritized extinguishing fires as quickly as possible. “This has led to the Karuk Territory becoming essentially a tinderbox, ready to ignite and explode,” says Gibbons. “The areas that would traditionally have been burned, have instead become overcrowded with dry fuel loads from downed trees, an overgrowth of brush, trees that are overcrowded and not fire-adapted, and invasive species.”

Beetle infestations have wreaked havoc on northern California, leaving vast slopes covered with patches of dead, copper-hued trees. The pests are growing more prevalent as the climate warms and have killed millions of trees in Siskiyou County since 2010.

A few weeks before the Mill Fire, the McKinney Fire burned 60,000 acres in the county, destroying 185 homes and buildings, killing four people and injuring twelve others. On the same day the Mill Fire started, another fire in Siskiyou County, the Mountain Fire, ignited and burned for several weeks over nearly 14,000 acres.

The Mill Fire wasn’t the first to devastate Weed. In 2014, the Boles Fire wiped out a third of the city’s housing and damaged several buildings at Roseburg Forest Products. Darin Quigley, who was Weed’s fire chief during the Boles Fire, remembers spending hours spraying spot fires at the mill, including in a wood chip pile to prevent the blaze from spreading into a conflagration.

Most of the housing in Weed, Quigley says, is not resilient to wildfire, but Lincoln Heights was especially vulnerable. Most of the roughly 60 houses that burned were old, built decades ago with wood from the mill, and packed together on small lots. Many houses had tanks of kerosene for heaters and decades worth of family possessions. “That’s all fuel, unfortunately,” Quigley says. Trees, grass and other vegetation surrounding the homes also provided fuel. “There was no effort to do any fuel reduction around that community.”

It’s hard to say if such initiatives would have helped, given the hot, dry, windy conditions on the day of the fire, but Quigley says even thinning a 3-acre strip of woods sandwiched between the mill and Lincoln Heights could have helped firefighters get between the flames and the homes and frantic residents more quickly.

Robert Broomfield, 67, a Lincoln Heights resident who used to work at the mill, is mostly frustrated with Roseburg Forest Products. “Why store ash in a wood building to begin with?” he wonders, especially with a densely populated neighborhood downwind of any fire that broke out there. Several residents recall Shed 17 being so worn down, wind would occasionally tear off foot-long strips of its roof and drop them on Lincoln Heights. (A Roseburg spokesperson said he was not aware of this issue.) Smoke damaged Broomfield’s home, but the fire destroyed those of his mother, his sister and his aunt, along with his treasured ‘57 Chevy pickup that he’d restored.

He questions how the fire exploded so quickly with sprinklers on site and the city of Weed’s fire department located on the mill property. “Nobody was there to catch it before it got out of hand?” he asked as he ate Raisin Bran out of a paper bowl in a Weed hotel. Displaced relatives and neighbors shuffle in and out of the same breakfast room, greeting each other with weary smiles.

Wreckage from the home of DeAndre Thomas’s family.

Michael Kodas

When Broomfield worked in the mill in the early ‘80s, it was owned by International Paper Company (IPC) and employed 750 people. (Roseburg now employs 140.) International Paper had bought the company from Long Bell in 1956 and chose to abandon the company town model in Weed, meaning no longer would the mill—the only major employer to speak of—own all the local stores and housing. Rather, IPC sold homes and lots to residents at a reasonable price, according to historical accounts. In 1961, the city of Weed incorporated.

IPC was a busy place, running a door factory, a wooden box factory as well as a wood treatment facility known as J.H. Baxter Co. Toxic chemicals used since the ‘30s to preserve lumber turned up in tests by the Environmental Protection Agency in the ‘80s around the Baxter facility. Arsenic, carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), pentachlorophenol and dioxins had contaminated soil, groundwater and surface water at levels that threatened both human health and aquatic life.

In April 1983, the Siskiyou County Health Department temporarily closed Lincoln Park, where kids from Lincoln Heights played baseball and rode the merry-go-round until they were dizzy, for soil and water sampling. Stacey Green remembers he and his buddies hopping over streams of runoff from the mill in the park.

Tests confirmed dangerous chemicals were draining into the park and adversely affecting fish in a nearby creek. By 1990, the Environmental Protection Agency declared the shuttered treatment facility at the mill a Superfund site. It took several years to clean up.

Bob Hall, a former Weed mayor and longtime city councilman with a shock of white hair, worked at Baxter for 20 years. He recalls the attention surrounding the Superfund site, but for the most part, he says, there was little ire in the shadow of the mill that was still Weed’s biggest employer.

“In a company town, there’s a mentality, a tendency to look the other way,” Hall says.

Hall, who at 45 switched careers to nursing, tangled with Roseburg in 2006 over their plan to build the cogeneration plant that would create electricity for the mill as well as sell power to cities in California, including Riverside and Sacramento. Hall, who lives a half-block from the operation, was worried about air pollution, particularly since many in Weed believe their city suffers from abnormally high rates of cancer.

The city, however, has little control over the mill, which sits on a finger of unincorporated county land poking into the city. As Hall sees it, this arrangement leaves a “golden goose” generating tax revenue for the county, while the citizens of Weed shoulder whatever harms arise—pollution, traffic, fire.

When the county planning commission approved the wood-burning electricity plant, Hall was concerned that they never properly reviewed possible health or environmental harms and partnered with Mount Shasta Bioregional Ecology Center to appeal the commission’s decision. Roseburg, in turn, threatened to close the mill in response to the environmental group’s actions.

“They’re bullies,” Hall recalls of the company he was standing up to. For two contentious years, he was a target for some in Weed who feared losing their jobs. “Folks would be throwing rocks at my house,” he says. “That was a bad time for me.”

Roseburg did end up conducting health and environmental reviews, and the plant was built, though Hall’s concerns weren’t totally unfounded. In 2011, Roseburg had to pay $75,000 penalties due to violations of the Clean Air Act.

Hall battled with Roseburg over water as well as air. The most recent dispute with the company involved the city’s drinking water, which for 100 years came from a pristine spring at the edge of mill property. Decades ago IPC, the mill’s previous owner, agreed to provide water to Weed for $1 per year for 50 years.

As the lease approached its expiration in 2016, Roseburg told the city to find another water source, and some in the government suspected they wanted to sell the water to Crystal Geyser Roxan, a bottled water company they were already providing with some water. Hall felt the water rightfully belonged to the city, and digging and maintaining new wells to replace it would’ve cost millions of dollars. He and a nine-member group called Water for Citizens of Weed fought back, grabbing national headlines. Roseburg sued all nine members of the Water for Citizens of Weed, as well as the city, during this ordeal, though with the help of pro bono lawyers, a judge determined Roseburg’s filing was nothing more than an intimidation tactic known as a SLAAP (a strategic lawsuit against public participation) and dismissed the suit.

Ultimately, Roseburg, the city and Crystal Geyser Roxane worked out an agreement, though the city has had to raise its water fee by $9 per household to cover the cost of its new water lease.

The water fight, Hall believes, dinged Roseburg in the eyes of the community, but the Mill Fire will likely leave a lasting scar. Though he says Roseburg has acted “admirably” since the fire, even offering up to $50 million to victims to rebuild, the loss of the historic neighborhood weighs heavy.

“It breaks my heart to think we could possibly lose Lincoln Heights,” he says. And just as the legacy of redlining has left Black and brown communities throughout the country more vulnerable to everything from health threats to depressed property values, Weed’s segregated past, Hall says, plays a role in the Mill Fire’s tragic consequences. “There’s a case for systemic racism.”

Two weeks after the fire Ben Crump, a high-profile civil rights attorney who’s represented the families of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Trayvon Martin, toured Lincoln Heights, at one point kneeling down to look at a bouquet of flowers left for one of the women who died. “We’re here to make sure the Lincoln Heights community gets equal justice—that’s the most important thing here,” Crump told reporters.

The steps of a Lincoln Heights home where a woman died in the Mill Fire that destroyed the neighborhood.

Michael Kodas

Al Bearden’s pickup crawls through Lincoln Heights, now a grim, hollow ruin of ash, chain link fences and crumpled appliances as dark as charcoal. A few scorched vehicles sit in the middle of the street, where drivers appear to have decided to run for their lives.

In his 70s, with a tall and sturdy frame that worked well for him during his career as a probation and parole officer, Bearden connects people to places, reciting the names of residents like he’s reading from a yearbook. The Smiths, little Robert, Big Ev, “the woman in mumus who demanded hugs.” Though Lincoln Heights has grown more diverse since Bearden was a kid in the ‘50s and ‘60s, it remained the heart of Black life in Weed.

In the passenger seat, Bearden’s friend, James Langford, who was recruited from the Bay Area in 1974 to become the first African-American elementary school teacher in Weed, surveys the once-vibrant neighborhood.

“Fire sure makes a mess,” he says, quietly. Before moving here, Langford had assumed Weed was all white, having been told that there were no Black people between Sacramento and Portland.

He’s written about Weed’s overlooked chapter in the Great Migration story, and how Black students were immediately integrated into white schools when they arrived from the South, but how, until the civil rights movement of the ‘60s, the rest of the town retained a racist code of conduct. Bearden and his Black friends, for example, couldn’t eat ice cream inside the ice cream shop, there’s a separate Black cemetery tucked behind Lincoln Heights and residents have long felt low on the city’s priority list for services, including snow removal and working fire hydrants. Bearden says Black people in Weed are treated like “third class citizens.”

He’s frustrated that 2014’s Boles Fire didn’t lead to more action. Lincoln Heights probably would have burned in that destructive blaze had the winds not shifted. But there was never any movement on the part of local or state agencies to recognize and protect the historic neighborhood.

The fire, he fears, has left the community vulnerable to another force of change.

“I fear there’s going to be a lot of gentrification,” Bearden says as he slowly drives along empty streets. Much of the neighborhood was occupied by renters who may not return, and even if homeowners decide to rebuild, new city codes require bigger lots and garages.

Stacey Green, the councilman, wants Roseburg Forest Products held accountable for their part in the Mill Fire. Residents have filed a handful of lawsuits, including one wrongful death suit, in recent weeks. One suit in Sacramento Superior Court on behalf of a family, claims Roseburg Forest Products was negligent in its handling of the hot ash from its cogeneration plant, and failed to inspect its facility to ensure it was safe. The suit claims the company showed a “conscious disregard for the safety of the communities it serves to prioritize profits.”

Pete Hillan, a public relations specialist hired by Roseburg after the fire, says Roseburg has written checks to more than 2,000 fire victims, but declined to say how much that financial compensation totaled.

The company also had an annual contract of roughly $50,000 with the city of Weed’s fire department that guaranteed fire suppression and fire investigations. Though Hillan says that contract also included inspections of mill property for fire hazards, the contract itself does not specifically mention that. Weed’s fire department is mostly volunteer, with only two paid staff.

Siskiyou County, where Weed is located, pays about a half million dollars to Cal Fire for fire and rescue services, but the county does not pay them to conduct fire inspections of commercial buildings.

Among the remains of Lincoln Heights, there’s little to hint at its history. There’s no plaque or historic marker, just glimpses into lives interrupted. At DeAndre Thomas’s home, a page of Jamila’s multiplication homework somehow survived amid the cinders of the rest of the house. Her red swing set looks ready for her to come play.

At Stacey Green’s house, only the strings remain from his beloved Steinway baby grand piano. He had hoped the bible of his late father, who was a pastor, might be hiding beneath the ashes. No luck, but the two Baptist churches that bookend Church Street in Lincoln Heights stand untouched, the fire halting mere inches away.

Through his teens, Green spent many Sundays playing music in those two churches. He doesn’t want to read anything “mystical” into their survival, but at a time like this, they’re a nice reminder of the community that was.

He knows this wildfire won’t be the last. Climate change keeps warming and drying out Northern California’s forests, and that Weed wind isn’t going to rest. He wants Lincoln Heights, and all of Weed, better prepared for the next blaze that threatens the city.

“We’re tired,” he says. “No more ‘You have 10 minutes to leave or you’re gonna die!’”

For Robert Broomfield, whose home survived but beloved antique truck burned, the news that Roseberg was set to demolish Shed 17, as well as an attached storage warehouse this year, due to their age, just added another layer of frustration. “It was a disaster waiting to happen,” he says.

His dad first came to Weed from Mississippi in the ‘50s for mill work, and his family moved into their yellow and brown, two-bedroom Lincoln Heights home in 1964. His mom, who raised seven kids in that house, told Broomfield and his siblings to rebuild the family home “with love, not anger.”

Broomfield isn’t there yet. Not even close.