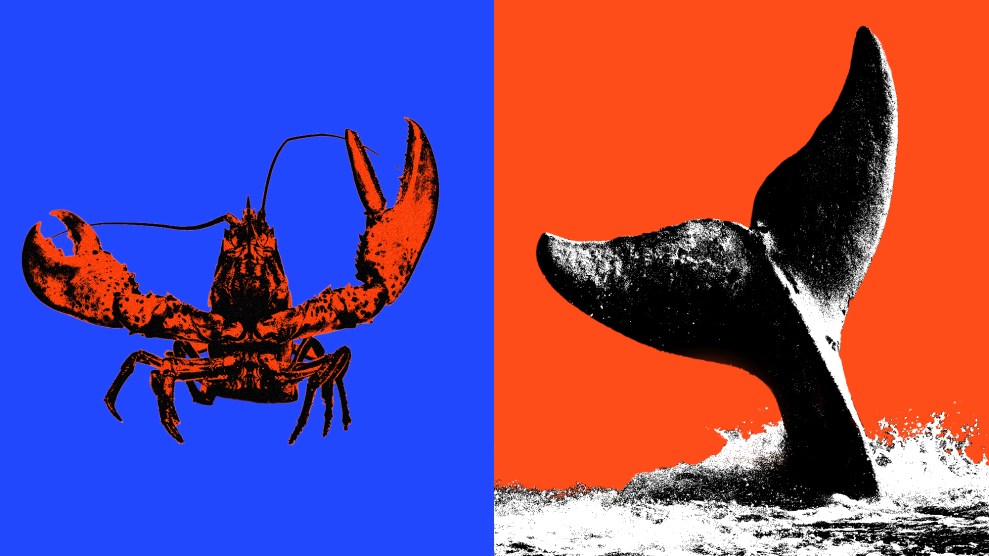

Green crabs will mate for days—but they’re less likely to start if their environment is too loud.Jack Perks/Alamy/Hakai Magazine

This story was originally published by Hakai Magazine and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The constant thrum of ship engines and other human noises can be a real nuisance for many sea creatures, disrupting their feeding, navigation, and communication. Now a new study shows that ship noise can also kill the mood for amorous crabs.

To date, most studies on marine noise pollution have focused on how it affects large marine mammals such as whales. Kara Rising, a graduate student in marine ecology at the University of Derby in England, however, was curious how it affects often-overlooked crustaceans. No previous studies have looked at how noise affects mating behavior in invertebrates, she says, despite its obvious influence on the success of a species. “All animals are there for the three f’s,” says Rising: “Fighting, feeding, and … mating. If any one of those is interrupted, you expect it to have some population effects.”

To find out how noise pollution affects crab mating, Rising collected male green shore crabs from beaches in Cornwall, England, and placed them one by one in a small aquarium. Next to the crab, she put a decoy female—really, a yellow sponge with toothpick legs doused in synthetic sex pheromones. “Sight is not the most important sense for the crabs when mating, but they do like a nice pair of gams,” Rising says.

Crab sex is more complicated than you might think. Shore crabs mate after the female has molted when her shell is still soft. The male rises up onto his legs and, with claws held outstretched, climbs onto the female’s back, wrapping his legs around her in a “love embrace,” says Rising. They stay that way for a couple of days, with the male protecting the vulnerable soft-shelled female until she is ready to release her eggs.

In general, the crabs seemed happy trying to impregnate the pheromone-soaked sponge. But then Rising started the real experiment. By playing recordings of ship sounds, she found that too much noise can disrupt this delicate affair. The crabs were far less likely to attempt to mate with the sponge decoy when it was loud than when it was quiet.

Researcher Kara Rising with one of the sponge mockups she used to attract male crabs.

Courtesy of Kara Rising

Carlos Duarte, a marine biologist at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia, says the work adds to scientists’ growing understanding of how animals are affected by noise pollution. He says this study is particularly significant because it’s focused on an understudied species and because it looks at how noise affects a behavior with a direct effect on population dynamics.

Duarte hopes that as it becomes clearer how many ways human-caused noise can affect marine species, regulators will take stronger steps to protect against it. “This adds to the pool of evidence that should eventually lead to more regulation of how humans introduce noise into the environment,” he says.

Rising says that because her study was fairly small and preliminary, there are things she’d like to investigate further under more robust, controlled laboratory conditions, such as whether males will abandon the females if the noise starts after they have established their embrace. But she says it is an important first step in expanding our understanding of the consequences of underwater noise.

“We should be looking more at how noise affects the species we don’t think about as much,” she says. “Everyone thinks about the whales, but the poor little crabs need to have sex, too.”