“Part of it is saying that this is okay to wrestle with—it’s more than okay; it’s crucially important.”Jonathan Sharfman/Slave Wrecks Project

This story was originally published by Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

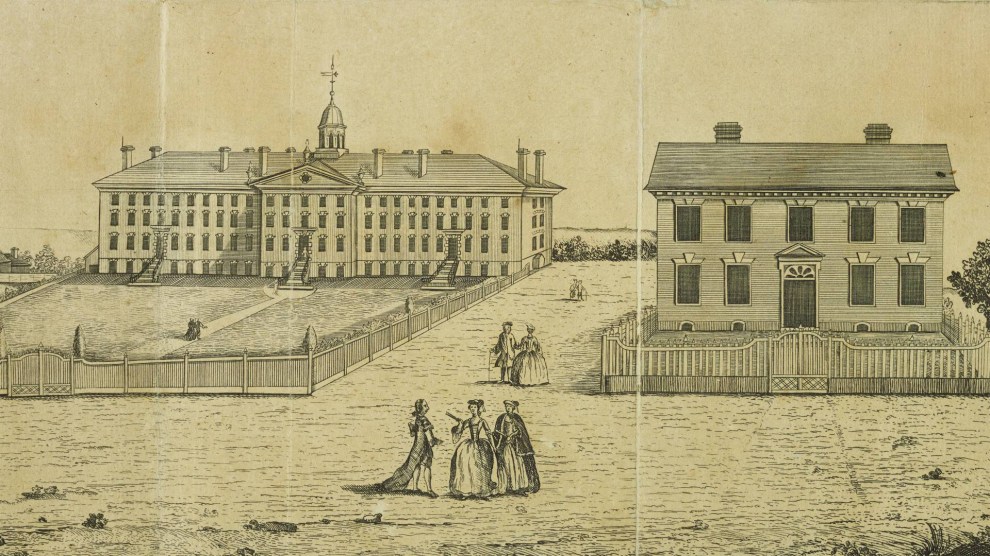

In 2015, a delegation from the Smithsonian Institution travelled to Mozambique to inform the Makua people of a singular and long-overdue discovery. Two hundred and twenty-one years after it sank in treacherous waters off Cape Town, claiming the lives of 212 enslaved people, the wreck of the Portuguese slave ship the São José Paquete D’Africa had been found. When told the news, a Makua leader responded with a gesture that no one on the delegation will ever forget.

“One of the chiefs took a vessel we had, filled it with soil and asked us to bring that vessel back to the site of the slave ship so that, for the first time since the 18th century, his people could sleep in their own land,” says Lonnie Bunch, now the secretary of the Smithsonian.

For Bunch and his colleagues, the importance of the find cannot be overstated. Although the São José—which was bound for Brazil—is the first ship to be recovered that is known to have sunk while transporting enslaved people, it was just one of the tens of thousands that plied their trade over the four centuries of the transatlantic slave trade, during which more than 12 million African men, women and children were enslaved.

And yet, as Bunch points out, maritime archaeology has tended to focus its masked eye on the wrecks of rich and famous ships rather than those that traded in flesh and blood.

Redressing that archaeological, academic and sociocultural imbalance was the driving force behind the Slave Wrecks Project, a partnership established in 2008 between the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) and other institutions and organizations in Africa and the US.

“People talk about the slave trade; they talk about the millions of people who were transported, but it’s hard to really imagine that, so we wanted to reduce it to human scale by really focusing on a single ship, on the people on the ship, and the story around the ship,” says Bunch. “Yes, we tell you about the thousands of ships that brought the enslaved, but we also say: ‘Here’s a way to humanize it.’”

The basic idea, he adds, was to tell people that “discovering your enslaved past is as important a treasure as finding the Titanic.”

A Slave Wrecks instructor trains divers in Ilha de Mozambique.

Robyn Leone/Slave Wrecks Project

As well as locating the wreck of the São José, the Slave Wrecks Project has developed programs to broaden and diversify the field by training people in Mozambique, Senegal, South Africa and the Caribbean in diving, archaeology and museum conservation and curation. Today, the project is investigating a handful of slave wrecks in Brazil, the Caribbean, West Africa, and North America.

“We need to think about how these matters that seem submerged and lost are really waiting there for us all to find, and to change our scope of how we understand our world,” says Paul Gardullo, a curator at the NMAAHC and director of the Slave Wrecks Project.

“This search is connected to something much, much bigger than any one particular search for a ship; it’s a search for ourselves and it’s a search for how we relate to each other in the world and how we make the world better.”

The Smithsonian’s activities, however, extend well beyond the seabed. Bunch and Gardullo have been in Lisbon for the past few days to take part in an international symposium on slavery, museums, and racism.

The choice of host country is not accidental. Like other former slave-trading colonial powers, Portugal – the European country with the longest historical involvement in the slave trade—has struggled to confront its past.

Last year, Europe’s top human rights body, the Council of Europe, urged Lisbon to rethink its approach to teaching colonial history, saying: “Further efforts are necessary for Portugal to come to terms with past human rights violations to tackle racist biases against people of African descent inherited from a colonial past and historical slave trade.”

The São José has helped the Slave Wrecks Project to better explain the slave trade and those it affected.

Jonathan Sharfman/Slave Wrecks Project

As Gardullo notes: “Portugal is very proud of its maritime heritage, but is very silent about that heritage’s connection to slavery and colonization.” Both he and Bunch hope the conference—which includes a one-day symposium with visitors from Angola, Brazil, South Africa, the UK, and the Netherlands—will reinvigorate stalled efforts to get Portugal to reflect on its past.

“Often we’re prophets without honor in our own land and in essence when someone else comes in and says these are important issues, suddenly that then stimulates a lot of what people are doing,” says Bunch. “Part of it is saying that this is okay to wrestle with—it’s more than okay; it’s crucially important.”

Last month, the Dutch prime minister, Mark Rutte, formally apologized for the role of the Netherlands in the slave trade, saying it had “enabled, encouraged and profited from slavery” and done things that “cannot be erased, only faced up to.”

For Bunch, the need for honest conversations “about the underlying issues that we have to grapple with” has been underlined by the murder of George Floyd, by Black Lives Matter and by the Brixton riots.

At its most basic, it is about being truthful about a painful and shameful shared history.

Copper fastenings, which held the ship together, and sheathing, which protected the exterior, recovered from the São José.

Erich Koch/Iziko Museums

“I think that people are really ambivalent about discussing slavery and looking at its past because the notion is: ‘Is this about guilt?’” he says. “For me, it’s about: ‘How do you understand yourself?’ There’s a big part of who you are—whether it’s Portugal, or Brazil, or the US—that you can’t understand without that. I’ve always been struck by how people are comfortable recognizing that their great-grandfather or great-grandmother’s DNA shapes them, but what they’re not as comfortable understanding is the history that shaped their great-grandfather and which also continues to shape them.”

It is also about respect, remembrance and perseverance. When the day finally came to scatter the earth from the Makua elder, the conditions in Cape Town were all too reminiscent of those that must have accompanied the sinking of the São José in December 1794.

“We’re there and we can’t get the boats out because the water’s so bad, the wind and the rain are so bad,” says Bunch. “The divers swim out as far as they can and then they sprinkle the soil. And on all that’s holy, the sun came out, the rain stopped, the wind stopped blowing. It was the most beautiful day you could imagine.

“I had never in my career really talked about ancestors or spirituality, but that moment made me realize that there is something so much greater than what we can be: literally the moment that soil was poured, the weather changed dramatically as a way to say that remembering is powerful.”