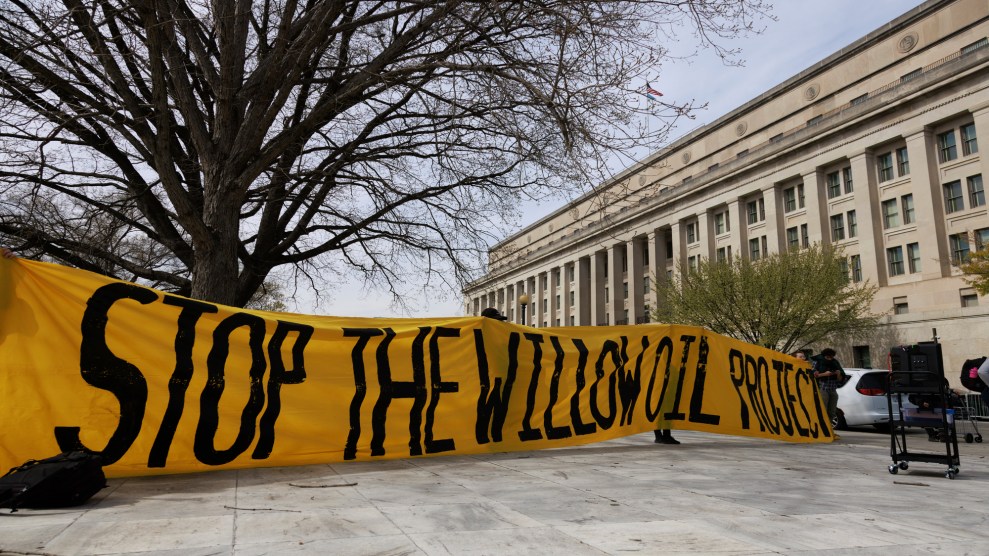

Arrival of canoes at Tribal Journeys, Cowichan Bay, B.C., Canada. Education Images/Universal Images Group/Getty

This story was originally published by Canada’s National Observer and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The floodwaters rose swiftly and silently inside Nicole Norris’s family home and other residences of the Halalt First Nation on Vancouver Island when a storm unleashed a furious deluge of rain in November 2021.

Her brother, asleep in the home’s ground-floor suite, awoke when his leg, hanging off the side of the bed, became submerged by overflow from the Chemainus River, said Norris, an Indigenous planning officer for the B.C. Ministry of Emergency Management and Climate Readiness.

“Our home took on four feet of water in the basement. There was no sound to it,” said Norris, also known as Alag̱a̱mił.

“Instantly, he yelled for my daughter and they were able to start pulling things from the basement.”

Not everything of value escaped unscathed, said Norris, a regalia maker, weaver and cultural knowledge holder.

Prints and artwork on the walls were warped from the moisture in the house. Thankfully, Norris’s cache of wool, loom and cedar hat equipment escaped damage because they happened to be in her apartment off-reserve, she said.

Not all families were as lucky, Norris said. A number of traditional weavers in the neighbouring Penelakut Nation lost wool, soaked and damaged during the flood, used to make button blankets or the area’s famous Cowichan sweaters. It was the second back-to-back winter flood to take place in the Chemainus region in two years, only to be followed by another in 2022, she noted.

Cowichan Tribes communities just north of Chemainus have also suffered extensive flood damage and a rash of evacuations in recent years. Ongoing climate change is only expected to provoke increasingly intense rainstorms, compounding the threat of flooding in the region and potential damage to valuable cultural artifacts.

Now, a new initiative will help First Nations protect and restore sensitive artifacts from climate disasters such as fires and floods, Norris said. In the Strathcona Regional District, $250,000 from BC’s Community Emergency Preparedness Fund will go toward Indigenous cultural safety training.

“We’re inviting First Nations communities from across Vancouver Island and the central coast to come and participate in workshops to learn the skill set to take care of their sacred items for themselves,” she said.

First Nations homes can resemble museums because they often house regalia, sacred objects, or traditional artwork handed down through families, Norris said. Though damage to houses or community infrastructure is generally accounted for, insured, and rebuilt following an emergency, the loss of valuable cultural artifacts like masks, carvings, blankets, paddles or totem poles often goes unacknowledged.

“When I’m doing rapid damage assessments in the community [after disasters], I’m looking at everything that didn’t get saved,” Norris said. “Some of these designs or artifacts were made by people who are long gone, and have been passed down through generations.”

The goal of the funding is to co-develop a pilot training program and then offer five workshops for First Nations on Vancouver Island interested in learning hands-on skills to preserve, recover, salvage, and restore community or generational belongings or artifacts, said Shaun Koopman, Strathcona Regional District’s protective services coordinator.

The first step is to team up First Nations regalia makers and cultural workers with emergency response personnel and planners and the BC Heritage Emergency Response Network (BCHERN), a volunteer network of heritage and restoration specialists.

Aside from developing workshop materials, emergency response personnel will learn to work in a more culturally sensitive manner with First Nations communities to recover artifacts after disasters, Koopman said.

There are gaps in the province’s disaster financial assistance to communities, which doesn’t consider the value of culturally important belongings, he added. BCHERN will also use input from First Nations to create guidance documents around the respectful and appropriate handling of baskets, masks, carvings, drums, feathers, regalia, and other items.

Ultimately, the workshops will train a core group of First Nations responders to act as a “sacred cultural item salvage strike team,” he said.

When disaster strikes, the end goal is to ensure that First Nations people are handling and restoring artifacts, especially sacred objects, which demand reverence and ceremony and which shouldn’t be exposed to people outside the culture, said Norris.

“We have rules around things that we are allowed to do and are not allowed to do when it comes to regalia,” Norris said. It’s important to identify items that are sacred and should only be handled by a First Nations curator, she added.

Norris has participated in a previous BCHERN restoration workshop and believes it is valuable at an individual and community level.

Sacred objects or articles crafted by regalia makers take a lot of time and money to produce and are often a critical source of income for those artists, she added.

“I personally would be devastated if I’d lost my wool or my cedar, or if my weaving loom was compromised,” Norris said. “This is about the preservation of that intimate cellular relationship that we have with our ancestors.”

Aside from preventing losses locally due to climate disasters, expanding First Nations’ technical ability to protect and restore artifacts is also important for communities looking to repatriate artifacts from museums taken at the height of colonialism, said Mindy Ogden, heritage place specialist for Ka:’yu:’k’t’h’/Che:k’tles7et’h’ (Kyuquot/Cheklesath) First Nation on western Vancouver Island.

“We’re thinking about the future, too, if we do set up display cases, or an artifact room for the repatriation of some sacred objects from museums,” she said. “Museums don’t always release those objects too easily. They might have some questions about how we are going to guarantee the safety of this object.”

Creating an inventory and assessing how the climate crisis or natural disasters, like tsunamis, might impact sacred sites or locations with cultural significance are of concern to KCFN’s emergency planners, Ogden said. “Sea level rise and worse storms with climate change, things like that are on our radar.”

“Things like middens and old village sites…they can start to erode away and then that information is lost.”

Protecting or restoring important objects from climate or natural disasters is vital to rebuilding and safeguarding First Nations culture after it was nearly erased, said carver Matt Jack, who is in the process of sculpting KCFN’s first village totem pole in decades.

Totem poles, a form of historical record, capture and reflect a community’s culture and significant happenings at the time they are carved, said Jack, also an elected legislative member of the KCFN government.

“Totem poles tell a story of the timeline we are in right now,” Jack said. “A lot of that’s been lost, like carvings, dance, and songs. So, we’ve been trying to rebuild and to do all this work, and to try to save it would be our story.”