Boats at the Monaco Yacht show in Monte Carlo, September 27, 2023MANDOGA MEDIA/picture-alliance/dpa/AP

This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The largest of the yachts in Monaco’s harbor were worth more than the annual GDP of some small island states. But few of the customers touring their decks seemed to care that buying the former would help drown the latter. “I don’t think about this yet,” said Elena Papernaya, an artist who had set her eyes on a mid-sized yacht, when asked if she worried about the damage it would do to the climate.

Kasper Hojgaard, a regional manager for an industrial company who charters yachts for a few weeks each year, said he did not consider climate change “at all” when doing so. His friend Lasse Jensen, a pension fund manager, nodded in agreement. “We are beginning to look a bit more into it, but it’s not playing a role.”

The Monaco yacht show is one of the greatest concentrations of wealth in the world. The event, which calls itself “the ultimate gathering of maritime luxury,” takes place in a tax haven where two in three residents are millionaires. When the Guardian visited in late September, the port was filled with more than 100 superyachts, some of which boasted submersibles and swimming pools. Visitors could book airport transfers in private jets and helicopters.

The true cost of such luxury is paid for, in part, by the rest of society. The top 10 percent of earners in the EU emit 24.5 times as much planet-heating CO2 through their transport as the bottom 10 percent do, according to new data from the International Energy Agency. At the extreme end of the spectrum, the carbon footprints of the ultra-rich are inflated by giant yachts, private jets and sports cars with engines that burn barrels of oil.

“There is no other way,” said Christian Largura, an Instagram star and founder of a luxury retail site who was about to buy a superyacht that runs on diesel. “For sure, if it’s possible, you take the green one…[but] if you want a big one, there is nothing fully electric.”

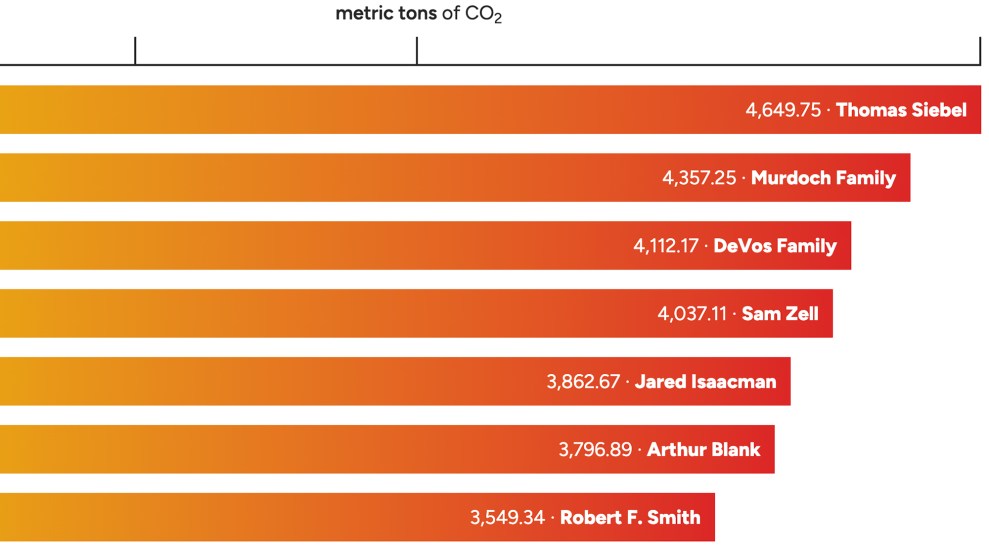

Billionaires’ consumption emissions run to thousands of metric tone a year, with transport, including private jets and yachts, by far the biggest contributor, according to Oxfam’s new report on carbon inequality. And transport, especially car use, is a major factor in the disproportionately high emissions of the richest 10 percent too, with these emissions 20-40 times higher than among the poorest 10 percent in major nations and blocs including the EU, according to the IEA.

A superyacht, or even a medium-sized motor yacht, is the most polluting single object a person can own. There are no reliable estimates of how much carbon the world’s 6,000 superyachts pump into the atmosphere but one study of billionaires’ footprints found yachts were the single biggest contributor, ahead of private jets. “Even a mansion on a private island has less impact because it is at least stuck in one place,” said Richard Wilk, of the Open Anthropology Institute, who co-wrote the study.

In interviews with 50 visitors to the Monaco yacht show—from brokers and buyers to suppliers and sellers—yacht enthusiasts painted a picture of an industry taking small steps to clean up amid growing public pressure. But only a handful of owners and customers who spoke to the Guardian said they were troubled by the disproportionate emissions their boats spewed today.

“You know that it’s something to worry about, but then again there are so many problems that we cannot fix,” said Giorgia Covolio, whose husband owns a yacht. “If I cannot solve it myself then I cannot stress too much about it.”

Jennifer Rodriguez, a friend, agreed. “If Bill Gates doesn’t stress about it, or Leonardo DiCaprio, then we won’t stress about it.”

While a small sailing ship may emit little more carbon than that required to build it and break it down, big motorboats burn vast amounts of fuel to cross seas and run power-hungry services such as air conditioning and desalination. According to a presentation by the industry group Water Revolution Foundation, the global yacht fleet spends a quarter of its energy on propulsion and three-quarters on “hotel load.” Some superyachts guzzle fuel even when docked because their crews live onboard all year round.

“The trend in yacht size goes towards bigger, bigger, and bigger,” said Lina Odhe, of SF Marina, a company that supplies to increasingly crowded marinas. The industry had moved “from superyachts to megayachts to gigayachts.”

The course that yachtmakers are charting is similar to one that the auto industry has navigated for several years. Carmakers have flooded the market with bulkier vehicles at such speed—and consumers have snapped them up so fast—that nearly half of cars sold last year were SUVs, according to the IEA. Experts put part of the success down to marketing campaigns that appeal to a desire for status and power.

By the dazzling waters of Monaco’s Port Hercules, surrounded by multistory ships and smooth-talking sales teams, most yacht owners and buyers approached by the Guardian declined to comment on their carbon footprints. Those who agreed to did so mostly on the condition of anonymity.

One owner verbally abused and physically threatened the reporter during a half-hour interview. Two potential buyers denied the scientific consensus that humans have heated the planet by burning fossil fuels.

Several attenders used identical arguments to those from regular rich people defending habits such as flying on holiday or driving an SUV. Some said their carbon footprints were not as big as those of even richer people. Others pointed to sources of pollution that were bigger in absolute terms, such as cargo ships, factories, and multinational corporations.

A handful of owners said they were aware of their own carbon footprints and frustrated at how little others had done to shrink theirs. “It’s one of the most unsustainable industries in the world, there’s no doubt about it,” said Frederik, a sustainability student from a yacht-owning family, gesturing at the port with a flute of champagne. “You’ve got here maybe three boats in total that are really trying to reduce their impact on the environment.”

He said his family had shrunk their yacht fleet down to two big boats, put solar panels and electric batteries on them and stopped dropping heavy anchors in areas with fragile seagrass that suck up carbon. “You need to make sure you’re having less of an impact every time that you use it.”

Jonathan, a friend working in luxury management, said he understood criticism of the industry, but he distinguished between people who bought big yachts to show off and those who wanted to spend private time with their families. He paused before adding: “The most valuable moments I’ve had were on the boat.”

The yacht industry has started to pay more attention to the environment. This year’s Monaco yacht show featured a catamaran covered in solar panels and boasted a “sustainability hub” for the second year in a row. Among the stalls were companies trying to power yachts with electricity and methanol instead of fossil fuels, as well as some trying to increase the efficiency of engines and hulls.

Javier Navarro, a broker with Zarpo Yachts, said the average age of a yacht owner had fallen to 42, and the younger generation of owners were more concerned about climate change. At the same time, advances in clean technologies in other sectors—such as car batteries getting smaller and cheaper—had made it feasible to electrify small yachts. “They are taking a lot of innovations from the car industry into the boating sector,” he said.

Some visitors were skeptical of the green marketing and the buyers nodding along to it. One crew member on a charter yacht said clients on her ship sometimes asked if the water they served came from plastic bottles, but did not mind spending weeks on a boat that guzzles fossil fuels. “I guess it’s nice to try to do what you can with the little things,” she said. “But really they’re scratching the surface.”

The total emissions from the yacht industry are probably a fraction of the overall shipping industry’s, experts say, but are caused by a far smaller group of people pursuing what is almost exclusively a leisure activity. And social scientists warn that the carbon footprints of the super-rich go beyond their raw emissions. Many people aspire to their lifestyles, particularly when glamorized in social media posts, and their emissions are often used by those with smaller footprints to justify polluting habits.

A junior associate at a law firm who lives in Monaco and was not attending the yacht show told the Guardian that the thought of such inequality frustrated her. “We make all these efforts in our own lives but when you see that”—she broke off and pulled a face at a row of superyachts hosting parties behind her—“well, it’s completely delirious.”