The Endangered Species Act has been one of the country’s most valuable environmental tools, but it faces new threats. As the law turns 50, we’re asking whether this “pit bull” of an environmental law, as one expert described it, can survive the challenges of our time—from political attacks to climate shocks. You can read all the stories here.

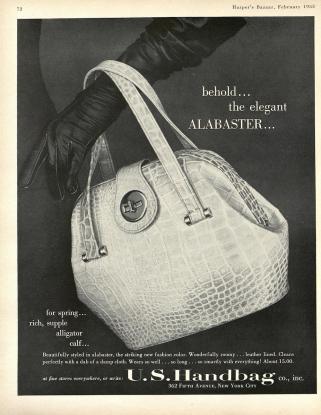

In the 1950s, alligator leather was all the rage. Advertised for its “supple” texture, durability, and ease of cleaning, an alabaster alligator calf handbag, according to a February 1953 Harper’s Bazaar advertisement, went for $175 in today’s currency. “Wears so well…so long…so smartly with everything!” the ad boasted.

But the real cost of this kind of purse was much greater than its department store price tag: After more than 100 years of being hunted for their desirable skin, by the 1960s there were fewer than 1 million wild alligators left in the southeastern United States—an estimated 80 percent drop from historic levels. “Ten years ago, you could drive the Tamiami [Trail] and see a hundred alligators,” a retired poacher told the Associated Press in 1968, referring to a highway that runs through the Everglades. “Now you’d be lucky if you saw two.”

By the late 1960s, the public had become increasingly aware of environmental issues—smog, oil spills, pesticides, and extinctions—like never before. The plight of the alligator captured the attention of the media, Congress, and newly elected President Richard Nixon, whose first interior secretary declared “war” on alligator poachers in 1969. As the New York Times editorial board wrote that year, predators like alligators “are part of the ecology of their portion of the earth—and a fascinating part. It is not for man to outdo them in predation.” The natural world, America had discovered, was finite and fragile.

This realization culminated in one of the most unique and powerful laws the United States has ever passed: the Endangered Species Act. “Nothing is more priceless and more worthy of preservation than the rich array of animal life with which our country has been blessed,” Nixon proclaimed after signing the law in 1973. “It is a many-faceted treasure, of value to scholars, scientists, and nature lovers alike, and it forms a vital part of the heritage we all share as Americans.”

Advertisement from Harper’s Bazaar, in 1953.

The Harper’s Bazaar Archive/ProQuest LLC

With Nixon’s signature, the ESA prohibited the “take”—killing, hunting, harming, collecting, and more—of the alligator and more than 70 other inaugural “endangered species.” The law also required government agencies to consider the impact of federally authorized or funded projects on listed species and their habitat.

After just a few years, the alligator quickly moved from a casualty of human negligence to proof that nature could be saved. Populations started to recover, and in 1987, the species was deemed to be “no longer biologically threatened or endangered.” Since then, it’s been classified as of the “least concern.” “Alligators really are almost like a poster animal for the Endangered Species Act,” Joe Roman, a conservation biologist and author of the book Listed: Dispatches From America’s Endangered Species Act, tells me. “Stop killing them, protect their habitat, and they will come back.”

Since Nixon signed the law on December 28, 1973—50 years ago this month—the ESA has helped dozens of species fully recover, including the humpback whale, bald eagle, brown pelican, and peregrine falcon, and prevented extinction for 99 percent of all species listed. (And it’s done all that, conservationists say, while being chronically underfunded by Congress by billions of dollars.) Even after 50 years, the act serves as a symbol of the country’s robust responsiveness to a planet in trouble—all packed into a PDF of fewer than 50 pages. “It’s not very long,” notes J.B. Ruhl, an environmental law professor at Vanderbilt Law School. “And yet here it is, this incredibly powerful, controversial, durable statute.”

When it passed, politicians considered the ESA to be a historic bipartisan success. It soared through the Senate unanimously (can you imagine?) and the House 390–12. But over the years, whatever flower of bipartisanship that had bloomed in the 1970s has since withered and died. Conservation, particularly of uncharismatic, ignoble species, became increasingly contentious, with Democrats largely landing on the side of plants and animals and Republicans with industry. Beginning in earnest under Reagan, conservatives repeatedly sought to weaken the ESA—and have given no signs of letting up. According to the Center for Biological Diversity, lawmakers (most but not all Republican), have launched more than 500 “legislative attacks” against the ESA since 1996—with 80 percent occurring in the last 10 years. Democrats, meanwhile, have largely played defense, Rep. Don Beyer (D-Va.), a member of the House Endangered Species Act Caucus, tells me, adding that he was unaware of any recent, Democratic-led efforts to strengthen the act.

Today, much like the plants and animals it safeguards, the ESA finds itself in trouble—and not just from industry-aligned conservatives. This series, Endangered, is about some of the ways the 50-year-old law is under threat—from political weaponization, or the climate crisis, or garden-variety government bureaucracy. In other cases, weak spots in the law have undermined it from within.

As I discovered while reporting a dispatch about the Venus flytrap, the ESA is designed to be nature’s “emergency room,” but it does little to protect species from landing there in the first place. Some say it has been deployed as a political cudgel, as my colleague traces in a piece about two threatened mussels caught in the crosshairs of a battle over a border barrier. And it has been used, at times, as in the case of a toad and a geothermal plant, to block renewable energy projects that some argue would help endangered species by reducing emissions. The law is burdened by an absurdly long waitlist, where species often languish in limbo for more than a decade—and sometimes become extinct in the waiting room. And, as one of my colleagues writes, it’s fueled our (perhaps unhealthy) reliance on zoos.

That’s not to say the act isn’t powerful. In fact, the experts I spoke with say we need this “pit bull” of a policy more than ever: In the last half century, the planet has lost about 70 percent of its wild animals, and more than a million species are nearing extinction, threatening not just nature but the wellbeing of humans too. As the country’s preeminent biodiversity law, the ESA may be the country’s best existing tool to safeguard disappearing plants and animals—if we can save the act from ourselves.

The seven men who led the effort to write the Endangered Species Act—lawmakers, conservationists, and White House officials—painstakingly tried to prevent extinctions and preserve habitats, but they were hardly the first to do so. Conservation, after all, is an ancient practice: In 360 BC, Plato wrote about the hills of Attica in his homeland of Greece, where deforestation had caused erosion and flooding, writing that the landscape was like a skeleton of a “wasted body.” Around the same time, in the first-ever “game laws,” India banned the killing of some birds, mammals, and fish. Before the US Constitution was ratified, Newport, Rhode Island, became the first city in the region to establish hunting restrictions, followed by New Hampshire and New York, among other colonies, writes historian and conservationist Lowell E. Baier in his 2023 book, Codex of the Endangered Species Act. Today, 184 countries have signed the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, or CITES, an international effort to prevent over-exploitation of endangered species.

At the core of these efforts, and conservation broadly, is the desire to preserve the Earth’s living resources for the benefit of humans. “If a species, ecosystem, or ecological process, is destroyed,” Lee Talbot, one of the ESA’s co-authors and a leading environmentalist, wrote in 1980, “future generations will be denied its use.”

What good does nature do us? As Talbot wrote, the list is long: Some 40 percent of all medicines prescribed in the United States, for instance, are made of naturally derived ingredients. About 75 percent of the world’s food—fruits, nuts, coffee, legumes, and more—rely on wild pollinators to grow. Birds prevent the spread of disease by eating ticks and mosquitos; ants maintain soils; wetlands filter pollution; coral reefs protect against storm damage; and phytoplankton and trees sequester carbon. In 2014, scientists estimated these perks, so-called “ecosystem services,” benefited humans to the tune of $125 trillion per year—more than 1.5 times the world’s GDP at the time.

There are plenty of nature’s benefits we don’t yet know about, which is why Talbot believed it was important to preserve a vast diversity of species—even the ones with seemingly no value. Writing in 1980, he likened the destruction of a species of unknown value to astronauts throwing out life-support equipment “because they want more room and do not know what the equipment is good for”: tragically short-sighted. On top of that, scientists estimate that we’ve only discovered about one out of four or five species on the planet, making conservation of diverse habitats all the more important.

But more than that, the ESA is a reflection of our ideals. Preserving the nation’s “rich array of animal life,” as Nixon put it, wasn’t just a self-interested utilitarian goal; it was part of our perceived responsibility to the planet. This narrative helps to explain why so many Americans continue to support the act—a stunning 84 percent of the country, according to a 2023 poll by the environmental group Defenders of Wildlife—and why the act has managed to endure “aggressive challenges,” as Baier writes, while maintaining “its original noble vision and promise” for the last five decades.

But, boy, have people tried. Despite its popularity, the ESA has become exceedingly controversial, sparking more lawsuits than any other piece of US legislation, Baier estimates in Codex. He attributes this conflict to a central contradiction in the law’s design: While the ESA protects species that may end up benefiting us, it also often tells Americans what they can and can’t do on their own land. It’s liberty against stewardship, farmer against toad, dam against snail, shopping mall against bobcat—and, importantly, present against future. “The Act forces changes on human activities and land use,” Baier writes. “Those sacrifices call immediately, but the promise of life for species, and thus for us, and the happiness of enjoying wildlife materializes slowly.” Put simply, landowners, developers, and ranchers pay concessions today so nature can benefit decades from now. That’s an uncomfortable trade-off for many Americans.

At the same time, the ESA now contends with forces its authors likely never anticipated. Since 1970, population levels have more than doubled. The terms “climate change” and “global warming” didn’t even gain use until 1975, according to NASA, two years after the act was signed into law. “As we see more and more species threatened by climate change impacts,” Ruhl says, “the Act will be overwhelmed.”

What the ESA has forced us to learn, Ruhl says, is that recovering a species is hard. “If it takes 100 years of habitat degradation to bring a species to the brink of extinction, you’re not going to recover that species in 10 years. It could take 100 years.” And the idea of “recovery” looks a lot different than it used to. For the American alligator, it meant putting an end to poaching and protecting the reptile’s wetland habitat. But for species directly threatened by climate change—corals confined to a boiling-hot ocean, a wolverine in search of snow to build a den, a coast redwood fighting off drought—“protection” is a more elusive goal. For this next generation of climate-threatened species, our best bet, he argues, is to “solve climate change.”

Yet even as many wild animals are vulnerable to the effects of warming, there’s also evidence they can also help stave it off. New research in the field of “zoogeochemistry” shows that wild animals can have a profound influence on how the environment absorbs carbon. Mammals, as Roman explains, disperse seeds and nutrients, which allow carbon-sequestering trees to grow. Similarly, we now know alligators act as “ecosystem engineers” by digging small ponds that boost nutrients and support plant growth. As Roman says, “these wild animals and plants can be allies in the fight against climate change.” We just have to make sure they get the chance to do so.