Wreckage of a Norfolk Southern freight train that derailed last February in East Palestine, Ohio, dispersing toxic chemicals far and wide. Gene J. Puskar / AP

This story was originally published by Inside Climate News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

On March 20, 2023, Hilary Flint uploaded a new video to her TikTok account. The clip starts with a close-up of her face, her cheeks flushed and her gaze trained on the camera. The post is tagged #eastpalestine. “I live in Enon Valley, Pennsylvania,” she says. “Less than five miles from the Norfolk Southern train derailment.”

“Since the train derailment, my skin has been red like a lobster, especially any time after I shower. I’ve been breaking out, I’m incredibly congested, and I have psoriasis, but now it’s so bad that it bleeds,” she says, pressing one finger to her pink face, leaving a white impression behind. “So when they tell me that everything is safe here, that’s really hard to believe.”

A year after the derailment in East Palestine, Ohio, and seven months after her first post about her symptoms, Flint is still sharing videos tagged with #eastpalestine, and she is still experiencing health effects that she says began at the time of the accident.

On February 3, 2023, 38 train cars derailed in East Palestine, just a few hundred yards from the Pennsylvania border. Twenty of the cars contained hazardous chemicals like vinyl chloride, ethylhexyl acrylate and butyl acrylate. Vinyl chloride is a known human carcinogen, and exposure can also cause fatigue and dizziness as well as irritation to eyes, mucous membranes and the respiratory tract.

Some of the cars’ contents caught on fire, others spilled into nearby streams, and on February 6, the owner of the railway, Norfolk Southern, conducted a controlled burn of the cars that were originally carrying 115,000 gallons of vinyl chloride.

In an interview in January, Flint said she has rented a house in western New York in order to limit her time at her home in Pennsylvania. But whenever she returns, her symptoms do, too. “Within three days I’ll start to get nosebleeds, constant congestion, sinus issues, pretty much all the same problems that we’ve had for the past year,” she said. “They all resurface within about three days in my home.”

Flint is not alone: Other Pennsylvanians living near the accident site say they are suffering from alarming symptoms like hair loss, tremors and migraines. They fear for the long-term health of themselves and their families, and they wonder if their properties’ water, soil and air are truly safe. Many of those affected are women and children, groups who tend to be more vulnerable to chemical exposure. Because they live outside the one by two-mile radius set by the Environmental Protection Agency as a protective zone around the fire, they have often been stymied in their efforts to access resources like testing, medical guidance and funds for cleanup and relocation meant for victims of the accident.

In their quest for answers, residents like Flint have spent months contacting a laundry list of government officials and agencies, from state lawmakers and the governor’s office to the Environmental Protection Agency and the Pennsylvania Departments of Environmental Protection and Health.

“When you call, they ask for your address. And if it is outside of that one-by-two-mile radius, they go, ‘OK, sorry, I can’t help you.’ And that’s it,” Flint said, of calling EPA and DEP not long after the derailment. “Even though I understood they weren’t testing in the area, there was just no guidance at all.”

Carly Tunno, a resident of Beaver County, said she’s been directed from one department to the next in her attempts to find testing and gain a better understanding of the symptoms that she and her children have been dealing with since the derailment last year. “You just get the runaround, and then they give you another number to call and you never get anywhere. They take a message, say somebody will call you back. It’s very frustrating,” Tunno said. “We haven’t really gotten any answers; there’s not really any urgency or concern.”

In a statement about the governor’s response to the accident over the past year, Shapiro’s press secretary Manuel Bonder said that “Gov. Shapiro has been focused on delivering the support and resources Western Pennsylvania needs, protecting the health and safety of our communities, and holding Norfolk Southern accountable for the impacts of their derailment” from “the very beginning of Pennsylvania’s response to the Norfolk Southern train derailment in East Palestine.”

Bonder said that the governor had “directed the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection to conduct independent water and soil testing in close proximity to the derailment site and post the results online for residents to see for themselves, already delivered more than $1.4 million for first responders to recoup equipment losses from responding to the derailment, and ensured Pennsylvanians were not picking up the tab for the derailment.”

“More than one year after Norfolk Southern’s train derailment, the Shapiro Administration continues to work with local communities in Beaver and Lawrence counties to ensure Pennsylvanians are safe and deliver resources those communities need to recover,” he said. “The administration will continue that work for as long as it is necessary.”

A press release from the governor’s office from February 2 outlining the response to the derailment listed a train derailment dashboard created to connect residents with resources, a health resource network and continued testing by DEP and the Department of Agriculture, which has not found “any long-term contamination” in western Pennsylvania.

Pennsylvania’s DEP and Department of Health say it is “extremely unlikely” that anyone farther than two miles from the accident site was “exposed to chemicals or particles of concern.”

“Due to the relatively short duration exposure from this incident, health effects consistent with long-term exposure are not expected to occur,” the two agencies wrote in a Frequently Asked Questions document about the derailment. In February, DEP published an interim report on the past year of testing in western Pennsylvania that found “no evidence of contamination in Pennsylvania’s private water wells, surface water, and soil” related to the derailment.

In a statement provided for this article, an EPA spokesperson said that “no lingering volatile organic compounds would be present in Pennsylvania based on our monitoring, sampling, and scientific understanding of these chemicals.”

But a University of Kentucky health tracking study found that 64 percent of adults and 63 percent of children in the area around the site had experienced a new upper respiratory symptom since the derailment. Survey respondents included residents living in Ohio and Pennsylvania, both close to the site and more than 10 miles away. Other symptoms included rashes, sore throat, nausea, eye irritation, headache, cough, lethargy, and shortness of breath.

Erin Haynes, director of the University of Kentucky Center for the Environment and the leader of the study, said it was significant that 80 percent of those reporting an upper respiratory symptom lived within one mile of the accident and that the number decreased as you moved away from the site. “That’s what I would expect, but then, just to see it was like, ah, it’s there,” she said. “[People] are not lying. They’re telling the truth.” In the fall, half of respondents who reported symptoms said they were still experiencing them.

Some people living near the site are doing fine, Haynes said, and not everyone is worried about contamination in their homes or on their land. But based on the information provided by residents who have participated in her study so far, she believes there is a need to gather more data. “Not everyone is experiencing a health effect, but there are some who are, and we need to take that very seriously,” she said.

“Assuming that there’s some tight, confined area within which problems occurred is not very realistic,” said Beatrice Golomb, professor of medicine at University of California San Diego and the principal investigator for an ongoing public health study on the impacts of the derailment on people living in East Palestine and the surrounding areas, including Beaver County.

“We’ve heard from people all the way up into Canada, initially reporting seeing the same strange coloring in their water, and animals sickening,” she said. “The idea that, gee, just at the same time, similar things have been reported that far, with a pathway that was consistent with wind directions—for that to be unrelated would seem pretty unlikely. That there’d be no possibility that those chemicals can produce health effects is also just not a sensible inference to draw.”

Golomb said that the number of women who are experiencing symptoms has contributed to skepticism about long-term health effects’ relationship to the derailment. “We had heard from the East Palestine community that people were saying, ‘Oh, but it’s mostly women, so it must be all in their heads,’’’ she said. “But women are more chemically vulnerable than men for a number of reasons,” and children are, too.

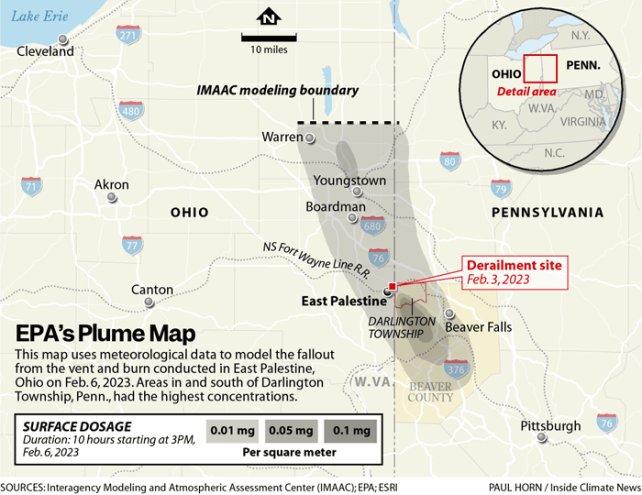

Residents point to the Environmental Protection Agency’s plume map of the soot released by the vent and burn, which shows the highest concentration of surface deposition in Beaver County on the Pennsylvania side of the border. Using meteorological data, the map models how soot released by six hours of burning traveled and then fell to the ground over time.

“We were just told you can’t possibly be affected because you’re too far away,” said Flint, who lives less than five miles from the site of the derailment and fire. “And it wasn’t until many months later that the plume map came out, and there you see the evidence that this plume went directly over all these PA communities. Yet none of those communities had access to help, especially early on.”

Unlike the circle of the official one-by-two-mile protective radius, the plume map depicts an oblong, irregular shape of potential contamination extending southeast into Pennsylvania. The EPA spokesperson said that early air monitoring confirmed “the presence of low levels of hydrogen chloride (below the health-based action level) and particulate matter” after the vent and burn, but that these contaminants “were no longer present after a few days.” Soil testing conducted after the burn on land affected by the smoke plume “indicated no additional risks to these areas.”

“I think it’s really important that regulatory agencies not look at this as black and white but rather look at this as a level of risk,” said Heather Hulton VanTassel, the executive director at Three Rivers Waterkeeper, a regional water quality and watershed health organization that has carried out recent testing on water and soil in the area. “We cannot argue that that community is at the same risk of exposure to these harmful contaminants as they were prior to the derailment. That’s false.”

Hulton VanTassel said that exposure levels differ based on air and water flows, and that some populations, like those with chronic illnesses, were more vulnerable to harm from the contaminants released by the derailment. People living near the derailment are going to have an increased risk, she said. “That does not mean every person who is exposed is going to get sick. It’s just that there’s an increased risk.”

For Hilary Flint, who is a cancer survivor, the seriousness of the derailment became tangible when she returned to her home for the first time after self-evacuating during the vent and burn. “All it took was opening the door to our house. The smell was so strong, it just immediately enveloped you,” she said. Flint said that within an hour of being home, she began to experience headaches, eye irritation and rashes, and that some of these symptoms—and the strange “sweet bleach” odor clinging to the rugs, fabric and furniture in her house—still linger, even now.

Hulton VanTassel said that Flint’s symptoms and experience of feeling sicker when she is at home are consistent with exposure to the kinds of chemicals released by the vent and burn. “That’s a pretty cause and effect relationship there, when that didn’t happen prior to the derailment,” she said. “Those are the types of symptoms that would occur with the contamination that we found in the sediment.”

Golomb said that participants in her study have reported similar experiences to Flint’s, of leaving town only to be sickened again when they returned. And there are other stories of potentially contaminated furniture and clothing. “We’ve had people who felt sick move to a relative’s house, and the relative opens the suitcase and throws up,” she said.

Flint started her search for testing by calling a phone number for the Norfolk Southern assistance center listed on television during a press conference. The number was wrong. When she eventually got the right number, she was dismissed as soon as she gave her address. The EPA and Pennsylvania DEP responded similarly, she said.

In May, after weeks of trying to reach state officials and legislators, Flint heard that the Shapiro administration would be hosting a small business resource fair in Darlington Township, close to where she lives, focused on economic recovery from the derailment. Flint suspected that the governor might be there, and she was determined to speak to him. She worked in her car in the parking lot until she saw Shapiro, and she and another resident approached him.

“We explained to him where we’re from, what we’re experiencing, how we’re not getting any help,” she said. “He was really receptive. He said, ‘I have gotten Pennsylvania residents money, and you just have to fill out this form.’” She said that someone from DEP then gave her a paper titled Business Loss Claims Information Sheet.

“I immediately read it, and I say, ‘Are you sure that this is right?’” Flint remembered. “Shapiro was assuring me, yes, and he was also with the DEP Secretary at the time, Richard Negrin. They were both telling us yes, this is the form, you just have to fill it out. That’s all you have to do.”

After she met Shapiro at the fair, Flint posted another video to her TikTok account. Sitting in her car, Flint holds up the paper from DEP. She says she questioned Shapiro when he handed it to her, asking how residents were supposed to know that this business-related form applied to them. “I will say, he was very kind,” she says. “I really do believe Governor Shapiro is an ally. But I hope he understands that this is not intuitive to anyone. No one knew this existed.”

Later, when Flint called the phone number on the form, she was told that she was not eligible to receive assistance this way.

The DEP form was a dead end, but during Flint’s brief meeting with the governor, she got a business card from Patrick Joyal, Southwest Region director for the governor’s office. Joyal put her in touch with a representative for Norfolk Southern, and in August, after seven months of persistence, she received some financial assistance from the company for the hotel bills she accumulated while trying to stay away from her Enon Valley home. The check did not cover all of her travel expenses.

Flint’s home has since been tested by Wayne State University, which she says detected vinyl chloride and ethylhexyl acrylate on her property. She is working a second job to pay for the rent on the house in New York, but she feels she has no choice. She still can’t get the smell out of her home despite many attempts to clean it. “The minute that laundry linen scent comes off, the sweet bleach scent is back,” she said.

Flint’s long battle for access to assistance is testament to the difficulties residents have faced over the past year navigating the tangle of federal, local and state government agencies, departments and offices that are responsible for the response to the derailment.

Tunno lives in Beaver County, seven and a half miles from the derailment site. When the vent and burn began, “the sky was so dark,” she said. “You could see the clouds roll in.” Her family was not told to evacuate, and they did not leave. “It was hard to breathe,” she said. “My kids had respiratory illnesses for the following days after that. My father-in-law was hospitalized, and he was diagnosed with pneumonia. I got respiratory distress, but I also threw up for days.”

For the next week, the birds she normally saw outside her house were gone. “You’d go outside, and you wouldn’t hear any. It was eerie and quiet. It was unsettling,” she said. When she went to empty out a bucket of her vomit, she noticed an oily sheen floating on the top of the bile.

Tunno said that her hair has been falling out since March, and she’s still beset by a sense of fatigue that wasn’t there before the derailment. Doctors were unable to explain her hair loss, telling her to wait four to six months to see if it grows back. She said she didn’t “jump to the conclusion right away” that her symptoms could be connected to the vent and burn, but when preliminary tests came back normal, she wondered.

“If you were losing your hair, you would want to know why,” said Tunno, who is 35 and works as a bartender and waitress not far from her home. Her extended family also lives nearby. “This was new for me. I’m generally healthy. I don’t really get sick that often,” she said. After she posted photos online of her hair loss, she said she’d heard from three other women in the area whose hair was falling out, too.

Tunno is also concerned for her three small children. “My children have been sick more in the past year and missed more school than they ever have,” she said. She is afraid there could be long-term consequences for their health and doesn’t know how she’ll afford to pay for medical care if they need it.

Tunno said her attempts to communicate with EPA, DEP, the Department of Health and local healthcare providers have yielded little clarity so far, and she is wary of signing up for university-led studies that publish results but may not hold anyone accountable for what they find. “I don’t feel like that should be the only option,” she said.

Christina Siceloff, who lives about five miles from the derailment site, in Darlington Township, still remembers the panic of the day of the vent and burn. “I was running all over the house,” she said, calling family and looking up hotels, trying to figure out where she, her son and her father could go if they needed to leave. “Finally, like 15 minutes before they did the release, I said to my dad, well, I don’t know where to go,” she said. “So I guess we’re just going to stay here and see if we die.”

After the vent and burn started, Siceloff went outside and walked up the hill from her house. “You could see this cloud across the sky,” she said, “and it would get closer and closer.” Within an hour, she said, her eyes were watering, her nose burned and she had a migraine and a cough, symptoms she said lasted for five months or more. The migraines persist, and she’s now taking allergy medication and on two inhalers. She was diagnosed with a fine tremor in December.

“All of that is new since the derailment happened,” she said. Siceloff twice visited a health clinic set up in Darlington by the governor’s office and the Pennsylvania Department of Health but found few answers there. She was told to visit her primary care doctor, who said she had an upper respiratory infection. “They diagnosed me with exposure to toxins that were non-occupational,” she said.

Siceloff contacted EPA, DEP and Norfolk Southern asking for testing of her soil and water and was turned away every time because she lives too far outside the radius. She was eventually able to get testing done by Purdue University, which did not detect contaminants in the well water but did find evidence of dioxins in the soil. She worries that her water could still be contaminated because the test sample came only from the top of the cistern. She would like to have more extensive testing of her water and better answers to her medical questions about what it means to be exposed to multiple chemicals at one time.

“Many of the symptoms that we’re hearing now, we saw before,” said Golomb, who previously studied Gulf War illness, a set of symptoms affecting veterans of the Gulf War that is linked to chemical exposure and especially to multi-chemical exposure. “We already have people that are fully meeting the symptom criteria for so-called Gulf War illness, which is a chronic multi-symptom health problem,” she said.

Migraines, fatigue, asthma and respiratory issues, as well as dermatological problems like rashes and hair loss, are all consistent with reactions to multi-chemical exposure, Golomb said. “People are sick,” Siceloff said. “And some people seem to be getting sicker.”

Misti Allison, an East Palestine resident who has become a community and public health advocate in the wake of the derailment, said that “healthcare monitoring is an unmet need” in both Ohio and Pennsylvania. “I want to have some type of framework in place so that the medical providers in the area know what they should test for and the questions that they should be asking,” she said. “Because in the very beginning, a community health needs assessment was not done. There has not been a database that has been created.”

A database could be used to monitor long-term health impacts of the derailment on the population, Allison said, and keep track of residents, like Siceloff, who have developed new chronic conditions since the vent and burn. Allison also believes that medical care should be covered for people whose health has suffered because of environmental exposure.

“I don’t feel like anybody is looking for a handout,” Allison said. “I know there’s some people that will say that we are trying to take advantage of a bad situation. I don’t feel that way. I feel like the overall sentiment in town is that people are just scared.”

Although Darlington Township is a rural area with fewer than 2,000 residents, the rail lines carrying vinyl chloride and other hazardous chemicals extend across Pennsylvania, through much more densely populated parts of the state. The same train tracks also run west and then south, through Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, Arkansas and Texas, according to a new report from Toxic Free Future, an environmental health research and advocacy organization.

“At any given moment up to 36 million pounds of toxic vinyl chloride are being shipped via rail by America’s largest producer, OxyVinyls,” the report explains. In Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia, more than 14 million people live within one mile of an active rail line, recent research from FracTracker shows. An East Palestine-like derailment in a more urban area could be catastrophic.

After the derailment, Flint co-founded a community grassroots group, the Unity Council for the East Palestine Train Derailment, that has advocated for the needs of impacted residents in Ohio and Pennsylvania and to improve the systems currently in place to respond to environmental disasters like East Palestine.

But she still feels that some Pennsylvanians are being left behind. “It’s not the majority of the community or every single person, but it’s a lot of women and children and people with preexisting health conditions, because we are more susceptible to certain chemicals and chemical exposure,” Flint said. “Just because we’re not the majority, it doesn’t mean that our needs don’t matter.”

“The impact on people’s lives has really been the most heart-wrenching part of this,” Golomb said. “The stress and worry about, what does this mean? What will happen? Do we need to move?”

Most people cannot afford to leave their homes, no matter how sick they feel there, and the lack of aid from the government has led to a “loss of faith in their country’s institutions,” Golomb said. Even if they do manage to leave, they still face difficulties in finding work and the grief of saying goodbye to their homes, belongings and extended families. “They’re really feeling left behind and forgotten by the government,” she said.

When Darlington Township received $660,000 from Norfolk Southern for “community relief” in July, the money was deposited into a high-yield savings account for first responders and future emergencies. “I want everyone to have access to resources, but what about the people?” Flint asked. She wanted to know: where was the assistance for people who are not farmers, small business owners or firefighters?

“We’re sitting here poisoned in our homes, and no one’s helping us, and everyone’s just pointing the finger at the other person,” she said. “It’s been a year now. This has been happening for too long.”