A flare burns at Venture Global LNG in Cameron, Louisiana.Martha Irvine/AP

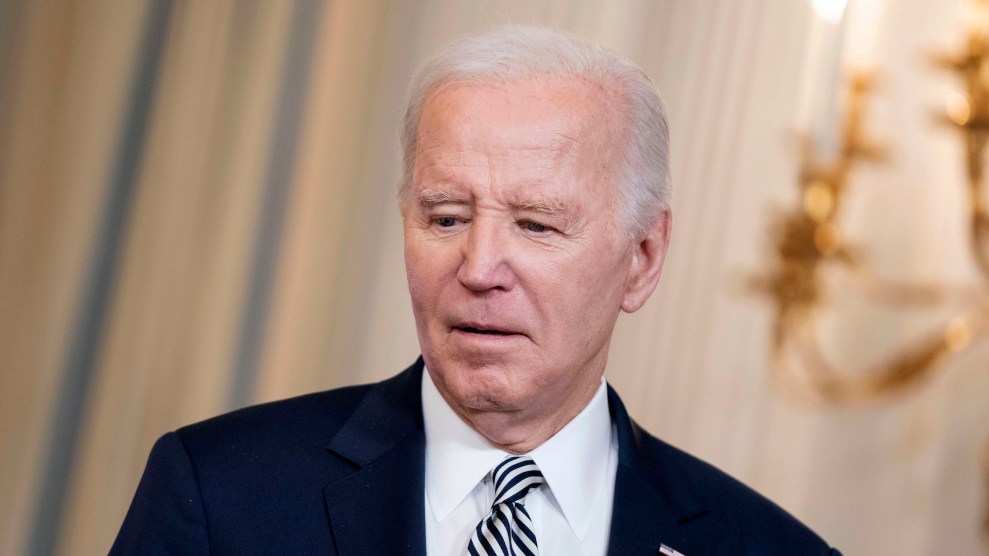

In a major win for environmentalists, the Biden administration announced late last month it would put a temporary hold on new export permits for liquefied natural gas to “take a hard look” at the impacts of the fuel on “energy costs, America’s energy security, and our environment.” In a statement explaining the hold, Joe Biden gave credit to “young people and frontline communities who are using their voices to demand action from those with the power to act.”

One of those frontline activists picking up the megaphone, so to speak, is Elida Castillo, the program director of Chispa Texas, a local initiative of the League of Conservation Voters, who is sounding the alarm about the dangers she says LNG projects pose to the people living in their shadow. Castillo has worked for years to push back against the growing number of industrial facilities in her community, including the Cheniere LNG export facility in Gregory, Texas, on the Gulf Coast.

Liquified natural gas, or LNG, is gas that’s been super-cooled to about –260° F, at which point it becomes liquid, making it easier to ship around the world. According to the Department of Energy, there are currently eight existing facilities in the country that export LNG, with more than a dozen already approved for construction, mostly in Louisiana and Texas. After the war in Ukraine sparked an increase in gas exports, Castillo says, she and other communities along the coast began to organize as a coalition against the terminals. As the Guardian reports, environmentalists have billed these projects as carbon “mega bombs” with the potential to release 3.2 billion tons of greenhouse gases, or as one researcher estimates, roughly what the entire European Union emits in about a year. On a local level, some worry about the health impact of the terminals’ pollutants, which include volatile organic compounds, carbon monoxide, and more.

Castillo, who was born in and is currently residing in Taft, Texas, just eight or nine miles from Cheniere’s LNG export facility, tells me that “flares” from the plant, the burning of excess fuel, happen constantly, causing noise and light pollution for residents. Add to that the possibility of explosions: As Castillo vividly recalls, part of an LNG facility in Freeport, Texas, went up in a ball of fire in June 2022. No injuries were reported to authorities. But to Castillo, it was an example of the dangers the facilities pose. “I have family members who live there, I have friends who grew up there,” she says of Gregory, “and they’re worried that this area is going to become completely owned by industry,” she says.

Ahead of Biden’s announcement, Castillo and about a dozen other collaborators attended permit hearings, knocked on doors, and met with lawmakers to oppose new LNG export permits and the expansion of Cheniere’s already existing LNG facility. At the same time, local environmental groups across Texas and Louisiana joined Chispa Texas in opposing the terminals in their region, along with national groups including Earthjustice, the Sierra Club, and the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Castillo tells me she sees Biden’s hold on new LNG terminals as a “good start”—but far from the end of the road. “When we got the decision from the Biden administration to put a pause on LNG exports, I was like, ‘Okay, I can take a breath.’ But it wasn’t something that we could take a deep breath and relax, because there’s still so much to be done.”

You can read an edited and condensed version of our conversation below:

How did you start organizing against LNG exports?

About three months into the job, in the summer of 2021, I got the opportunity to go to Europe. At the time, there were a few LNG import terminals proposed for Germany. The Sierra Club and the Texas Campaign for the Environment were like, we need people from the community [to go to Germany] because some of the contracts they’re pursuing will be from Cheniere, and we need more community voices on this. Fracking is banned in Germany and other places in Europe, but they don’t mind buying gas from other countries without considering impacts on the community. After coming back from that trip, it really accelerated our work on LNG.

Can you tell me more about what has been going on in your community?

A few months ago, a group of us were out about a mile from the Cheniere terminal, canvassing, fliering against a proposed highway expansion project. The flare was on, and there was just this noxious smell, and I started getting this really bad headache. And people in the group were like, “Yeah, this is the way it is.”

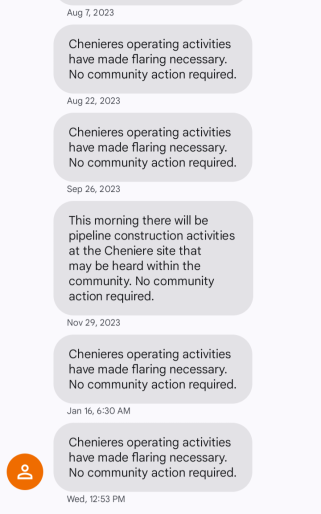

When the flare is really big, people’s windows rattle. And they say they can hear this constant whirring noise, like the burner on your stove. It just sounds massive, especially at night. It’s been a scare for them. If you know to sign up for the alerts, you receive alerts. But they always say, “No community action is required.” Or the local sheriff’s office will post something like, Cheniere has a flare, but y’all don’t need to worry about it. Everything is good. But nobody knows exactly what’s in that air that we’re breathing.

A list of recent community alerts received by Castillo.

Elida Castillo

Our community members in Gregory joke about it. They call it “Motel Six” because they “leave the light on for you.” Others call it “The Eye of Sauron.”

We have talked to parents whose children have never had respiratory issues before, and now they’re having to use nebulizers. People are getting headaches. There’s just so many different projects [in Gregory] that it’s really hard to track what it’s related to, but people have been reporting more respiratory problems. [Editor’s Note: When reached for comment, a spokesperson for Cheniere pointed to a 2023 “report card” by the Gregory Portland Air Monitoring Program, a research group funded by Cheniere Energy and petrochemical company Gulf Coast Growth Ventures, with data provided by researchers at the University of Texas at Austin, which found that “air quality standards set by federal and state agencies continue to be met.” They also added that flaring at their facilities “is minimized to the maximum extent possible.”]

Even to this day, after all the organizing and conversations we’ve had, there’s still some hesitancy for people to get involved because they either know somebody who works in the industry or they’re afraid of getting blacklisted. My own brother deleted me from social media because he tried to get a job at one of the facilities and he’s like, “This is gonna hurt my chances.”

Are you concerned about your brother’s health? Have you had conversations with him about that?

Oh, absolutely. He’s my older brother. We’re just on two different sides of things. He’s pro because he sees it as a job opportunity. But a lot of them are contract positions, and people get injured or sick and they just leave. He worked at Sherwin Alumina’s aluminum facility when they closed down and it filed for bankruptcy. They had all these people, you know, left out of a job. There’s no job security there. But, you know, he’s stubborn. I’m just as stubborn.

But I am concerned about his health and also his safety because he lives very close to the facility. What if there’s an explosion? With so many different facilities close to each other, we just don’t know what to do in the event of something like that happening. We saw what happened in Freeport in 2022.

I want to touch on the Biden administration’s recent announcement to pause new permits for LNG exports. What was your reaction to the decision?

I had heard rumblings about it. But we didn’t know what to expect until it was actually announced the morning of. And they’re going to place a pause on LNG facilities, but it doesn’t stop those that are already in operation or have already received approval. So it’s a step forward. But it doesn’t help communities like mine, it doesn’t help communities like my friends in Cameron County or in the Carrizo Comecrudo tribe in the Rio Grande Valley. We’re still being affected by the LNG facilities that are already in operation, and there have been two facilities in the area that have been approved already, Rio Grande LNG and Texas LNG.

A lot of these projects started after 2015. So we don’t need more time to see if it is impacting our communities. It is absolutely impacting our communities.

This is a critical year for Joe Biden. Some have speculated that his decision to pause LNG projects may have been a play to young voters, or people who care about climate. What do you think about that take?

That’s what we’ve heard as well. That they needed to do something because more frontline communities, environmental [voters], and young people were concerned about his record. People all over were disappointed. He ran as an environmental justice president. And yet, we saw about double the amount of [natural gas] exports under his leadership. And so there was that disappointment.

What’s next for you?

We’re going to be focusing on FERC, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, because the Biden administration’s decision doesn’t impact their ability to approve permits and pipelines. They can still approve permits. And when the Department of Energy conducts its study [on the impact of LNG], we’re asking for them to include community voices.

This is a good start. But we can’t become complacent just with this decision. There’s a lot more that can be done. I know Secretary Granholm has said this is a temporary pause, but it can’t be temporary. This needs to be a permanent pause.