Zuma; Wikimedia

This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

In the 19th century, the German zoologist Christian Bergmann pondered a simple question: Why are some animals so small? His answer, that a warm-blooded animal’s size increases as its habitat cools, remains a rule in biology to this day.

“Bergmann pointed out that smaller species tend to live in warmer climes. This pattern is to do with surface area and volume: Smaller animals lose heat faster and struggle to maintain their body temperature when it is very cold,” says Simon Loader, the principal curator of vertebrates at London’s Natural History Museum. “Whatever the reasons, these small species are fascinating,” he says.

With much of life on Earth still unknown, scientists are discovering new tiny organisms every year, redefining what is considered the smallest of their kind—and some claims about who is the smallest of them all are hotly contested.

Tiny creatures can sometimes struggle to get the same conservation attention as their larger, charismatic counterparts. “The small species often get over looked or missed,” says Paul Rees, a nursery manager at the city’s Kew Gardens. We asked scientists to tell us about the smallest creatures of their kind.

Brookesia nana, less than an inch long, rests on a vine.

Wikimedia Commons

Smallest Reptile: Brookesia Nana-Chameleon, Madagascar

First described as a species (discovered by science) in 2021, a male Brookesia nana is just 0.8 in long and is found in the rainforests of northern Madagascar. Females are larger, growing to nearly 1.2 in. Researchers believe the world’s smallest reptile is critically endangered, found in an area that has been severely degraded by deforestation.

Despite its overall size, Brookesia nana is considered remarkable for its disproportionately large male genitals, known as hemipenes in snakes and lizards. “The miniaturized males may need larger hemipenes to enable a better mechanical fit with larger females,” says Loader.

Madagascar is famous for its small animals, including several miniaturized frogs and Madame Berthe’s mouse lemur, the world’s smallest primate.

A bee hummingbird.

Lee Dalton/Evolve/Zuma

Smallest bird: bee hummingbird, Cuba

The bee hummingbird (Mellisuga helenae) weighs as much as a paperclip, and measures just 1.9-2.3 in. Mainly found in dense forests and on the edge of woodlands in Cuba, its eggs are the size of a coffee bean and its wings beat 80 times a second. Due to habitat destruction on the Caribbean island, scientists are concerned about its survival.

“Its population is thought to be declining at a rate of 20-29 percent a decade due to forest loss and degradation, and has already disappeared from many areas where it was formerly widespread” says Ian Burfield, the global science coordinator for BirdLife International. “Like other hummingbirds, it feeds on nectar from a range of flowering plants and plays an important ecological role as a pollinator, so its decline is doubly concerning,” he says.

Dicopomorpha echmepterygis parasitic wasp.

John T. Huber, John S. Noyes, J. Read/Wikimedia Commons

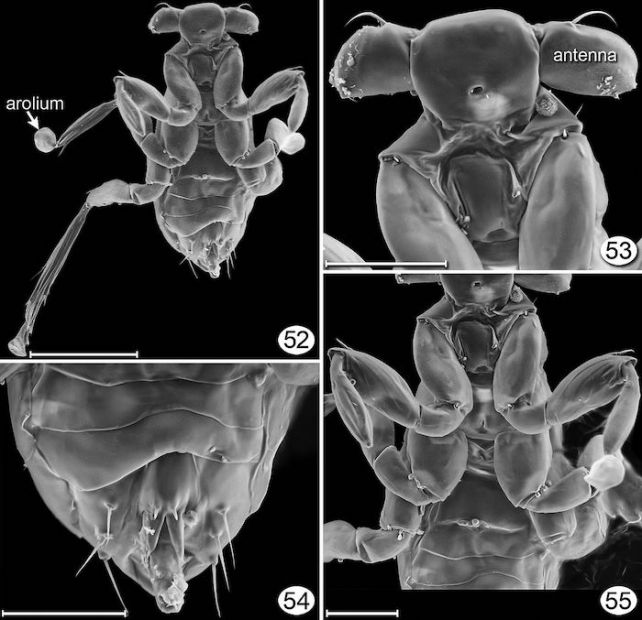

Smallest insect: Dicopomorpha echmepterygis, parasitic wasp, USA

The world’s smallest insect is so tiny that it is smaller than some single-celled organisms. As little as 0.006 in long, the US parasitic wasp spends most of its life inside its host, the bark louse.

“A species of ‘fairyfly,’ these are tiny wasps which develop as parasitoids, with eggs laid inside the eggs of bark lice, which are not too large themselves,” says Gavin Broad, the principal curator of entomology at the Natural History Museum.

“One female wasp develops in the host egg, eating most of the contents, accompanied by one to three males, which lack wings, have rudimentary heads and are generally simplified as they never leave the egg; they are just there to fertilize females,” Broad says.

Smallest amphibian: Paedophryne amauensis frog, Papua New Guinea

This tiny frog is so small it does not have tadpoles. Described in 2012, the frog lives in rainforest leaf litter, feeding on ticks and mites.

“Unlike many other frogs, its life cycle does not include an aquatic tadpole stage. Instead, tiny froglets hatch directly from eggs that are laid in moist leaf litter on the forest floor,” says Dr Jeff Streicher, the principal curator of herpetology at the Natural History Museum. “Adults feed on small invertebrates found in the same leaf litter. This lifestyle is common in other small frog species, which highlights the essential role that leaf litter microhabitats play in the survival of these tiny amphibians.”

An Etruscan Shrew

Lies Van Rompaey/iNaturalist/Wikimedia

Smallest mammals: Etruscan shrew and bumblebee bat

For mammals, it is hard to separate two tiny contenders. The Etruscan shrew, found across parts of Eurasia and north Africa, weighs between 1.2 g and 2.7 g on average. It is solitary and active mainly at night while feeding on invertebrates. The tiny shrew lives a short life, rarely surviving its second winter, says Paula Jenkins, senior curator of mammals at the Natural History Museum.

The other miniature mammal considered the world’s smallest is the bumblebee bat, also called the hog-nosed bat, which is found in two isolated populations in Thailand and Myanmar. It also weighs about 2 g, with a wingspan of up to 5.7 in and a body length between 1.1 in and 1.3 in.

“It roosts in extensive caves in limestone outcrops near rivers,” says Jenkins. “Individuals roost separately at some distance from each other. They hunt for invertebrates in the upper canopy of the forest using echolocation to detect their prey in flight, and may also pick prey from foliage.”

Wolffia globosa, the world’s smallest flowering plant, under a microscope

Andrey Zharkikh/Wikimedia

Smallest flowering plant: Wolffia globosa, Asia native found around the world

Sometimes known as duckweed, Wolffia globosa has the fastest known growth rate of all plants and can quickly cover entire bodies of water. Despite lacking common plant organs such as leaves, roots, and stems, it produces the smallest known fruit and is highly nutritious.

Tom Pickering, the senior manager of display glasshouses at Kew’s Royal Botanic Gardens, says the plant is weed-like in appearance and nature. “This vigorous, free-floating aquatic plant is grown in tanks in the tropical nursery at Kew, and is globally used for animal food, medicine and food. Despite its size, Wolffia is in the same plant family as the titan arum, a flowering plant with the largest inflorescence in the world,” he says.

Paedocypris progenetica

Wikimedia

Smallest fish? Depends whom you ask.

The title of the world’s smallest fish is hotly contested. According to Guinness World Records, it is the quarter-inch male Photocorynus spiniceps, a species of deep-sea anglerfish found in the Philippine Sea that is sexually parasitic. It attaches itself to the much larger female—a trait common in anglerfish—in effect turning her into a hermaphrodite. She feeds, swims and ensures their survival—he just worries about reproduction.

But given the female Photocorynus spiniceps is several times larger than the male, other researchers say the title belongs to the Paedocypris progenetica from Sumatra, which swims around in peat bogs, growing up to 0.31 in as adults. The tiny Indonesian fish was scientifically described in 2006 and proclaimed the smallest—a claim quickly disputed by researchers who studied the anglerfish.

Blossfeldia liliputana

Mats Winberg/Wikimedia

Smallest cactus: Blossfeldia liliputana, Argentina and Bolivia

The Blossfeldia liliputana’s epithet comes from the word ‘lilliput,’ meaning tiny person or being, explains Paul Rees, a nursery manager at Kew Gardens. “It also refers to the imaginary country inhabited by tiny people in Gulliver’s Travels,” he notes.

Found growing on rock faces and in cracks at high altitude in Bolivia and Argentina, it can withstand extreme drought, losing up to 80 percent of its moisture content. Despite their versatility, the world’s smallest cactus is increasingly threatened by collectors.

“Over the years this species has been desired by collectors, and due to its very slow growth rate, a number of plants have been poached from the wild. Though its wide distribution means it’s listed as ‘least concern’, poaching remains the major threat to this species.”

View this post on Instagram

Smallest fungi: waiting to be discovered

After the tiny Mycena subcyanocephala was photographed in Taiwan last year and went viral on social media, some incorrectly said it was the world’s smallest. However, with an estimated two million species of fungi waiting to be discovered, there are likely many microscopic organisms waiting to be found, says Ester Gaya, the senior research leader in mycology at Kew Gardens.

“Mycena subcyanocephala is one of the smallest species of fungi in the world. Regardless of their minute size and ethereal looks, this species of fungus plays its role in the complex recycling system of nature. Mycena species are saprobes, meaning they live on decaying organisms, helping clear our woods of unwanted ‘litter’.”

With important roles ranging from nutrient recycling to carbon sequestration, she says: “As in all things small, it is often the coordinated work of multiple small fungi that has a large impact in our ecosystems.”