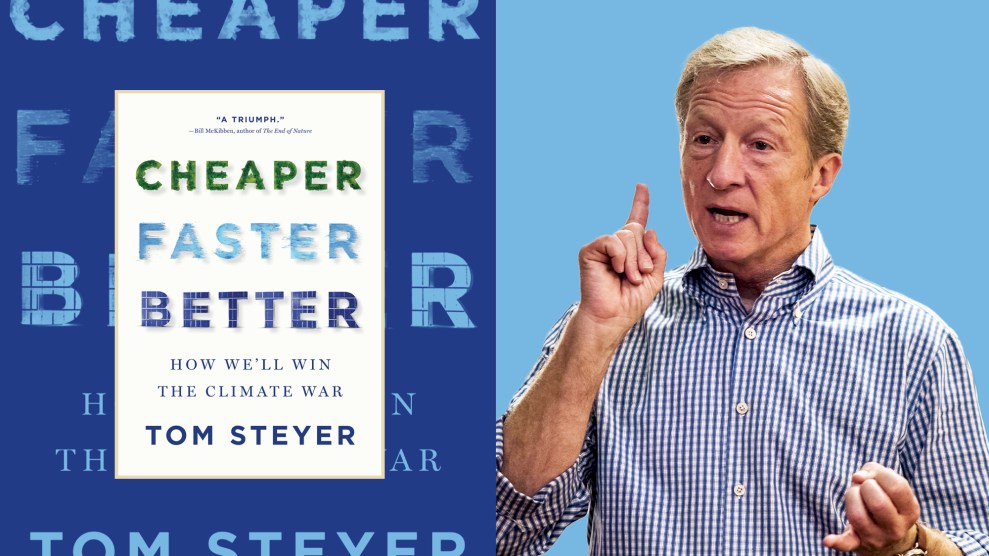

Mother Jones; Jack Kurtz/ZUMA; Spiegel & Grau

Tom Steyer is skeptical of human kindness—at least as a means to positive global change. As he describes in his new book, Cheaper, Faster, Better: How We’ll Win the Climate War, the billionaire climate activist argues that to address an issue as “complex” and “rife with self-interest” as the transition away from fossil fuels, the world can’t rely on companies and organizations to act out of sheer altruism. “I’m skeptical of any solution that requires humanity’s collective heart to grow three sizes,” he writes.

Instead, he points to another tool: capitalism.

It’s a force he’s intimately familiar with, and one he has clearly benefited from. You may remember Steyer from his recent bid for president—or maybe you don’t, because he dropped out in early 2020 after earning just 11 percent of the Democratic vote in the South Carolina primaries—but before that, Steyer earned a fortune as the founder of Farallon Capital, a hedge fund that under his leadership he says grew from $6 million to more than $20 billion over two and a half decades.

“I’m skeptical of any solution that requires humanity’s collective heart to grow three sizes.”

In 2012, after some self-reflection and an especially impactful meet-up in the Adirondacks with environmentalist and author Bill McKibben, Steyer left Farallon to pursue climate advocacy. (McKibben had just published an article in Rolling Stone titled, “Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math,” and Steyer heard him on the radio. “I cold-called him,” Steyer recalls, “and said, ‘You want to go on a hike?'”) In 2021, Steyer co-founded Galvanize Climate Solutions, a climate investment firm.

Still a “proud and committed” capitalist, he argues that “markets are the quickest way for human beings to change things at scale,” whether that applies to oil and tobacco or clean drinking water and vaccines. Markets, he writes, are amoral. And for a long time, fossil fuels ruled. But now, Steyer sees the world at a turning point. As he told me over Zoom in April, “cleaner is cheaper.” And for wealthy investors, himself included, doing the “right thing” by funding green solutions can also be profitable.

“Part business book, part climate manifesto, part memoir,” as his marketing team described it, Cheaper, Faster, Better reads as one long monologue in which Steyer argues that readers should become, like him, “climate people” and incorporate climate into “every big decision you make.” Throughout, he compares our fight against climate change to World War II: The question, “‘What are you doing to fight climate change?'” he writes, “is the ‘What did you do in the war?’ of our time.”

In a wide-ranging, 45-minute conversation, I asked Steyer about his views on carbon–footprint shaming, celebrities like Taylor Swift flying private, and what the super-wealthy owe the world. You can read an edited and condensed version of our conversation below.

You write about capitalism’s role in addressing the climate crisis. But capitalism is part of the reason we got into this mess. Why do you still trust it to work now?

When you think about capitalism’s role in society, capitalism scales. And the organizations that solve society’s needs and wants are profit-driven businesses. But it is absolutely essential that the rules be set up in society so that even self-interested individuals and organizations do what’s in society’s interest.

I think we’re at a point where the interest of business will be in providing sustainable answers, both because of the rules that government has put in, and the programs like the Inflation Reduction Act that are designed to say to people who are profit-oriented, “Build this. This is what our society needs.”

I think that business has to have frameworks from the government, and from, in effect, the will of the people to build the things that society needs. That’s how it’s supposed to work. That’s why I think the engine of getting this done will be capitalism, but it’s got to be within that framework. Carrots and sticks are critical.

If there are rules and incentives, and it’s in investors’ best interest to pay attention to climate change, as you argue in the book, why do so many still put their money into fossil fuels?

I think that it’s pretty simple. They’re betting on the status quo. They’re making money, a lot of money, from oil and gas right now. And they’re betting that that won’t change.

If something can’t go on forever, eventually, it must stop. And that’s where we are in fossil fuels. The status quo cannot keep going. In the last 10 months, every single [month] has been the hottest month in recorded history. We’re on a trajectory in terms of emissions and air temperature and ocean temperature that is absolutely unsustainable. We need to make this change. And now we’re at a place where, technologically, it’s to our advantage. Eighty-six percent of the new electricity generation in the world last year was renewable, for example.

There’s the old Hemingway quote, “How did you go bankrupt? Two ways: slowly, and then all at once.” New technologies will slowly eat away at the status quo, until then, all of a sudden, they go vertical.

You write in the book, “I’m pretty sure I don’t just have a carbon-neutral footprint, I have a carbon-negative one.” Why do you think that? Have you ever tried to measure it?

For a long time, we’ve been doing a huge experiment using rotational grazing and regenerative agriculture on a ranch [in the San Francisco Bay Area]. It’s a huge science experiment to see if there’s a different way of raising animals in a way that’s helpful to the soil, to the water, to the animals, and for CO2.

I believe that using techniques to put carbon back in the soil, in a substantial way, means I probably do have a negative carbon footprint. But I’m not sure. But as I said, carbon shaming is not the way to go. This is a societal answer. This is not something people can answer on their own.

[Editor’s note: Scientists say the jury is still out on how much carbon regenerative ranching can net-sequester on a global scale.]

Yes, you write in the book about carbon–footprint shaming, and how it can be unproductive to criticize public servants like [climate envoy] John Kerry who’ve flown on private planes for their work. What do you think about people on social media who track celebrities’ private plane trips? Like Taylor Swift?

I never fly on a private plane. I know what it looks like from an emissions standpoint, and it’s almost mind-blowing. And we live in a society where, basically, you’re allowed to pollute for free. For a long time, we didn’t realize that there are unintended consequences of burning fossil fuels. Now we know that, but we still don’t charge for it.

“If you’re not paying for your pollution, you’re basically making us pay for your pollution.”

My feeling is, if you’re going to take a private plane, that means, by definition, you’re rich. Which means you can afford to pay for your pollution. And if you’re not paying for your pollution, you’re basically making us pay for your pollution. Not just people in the United States, but people all over the world who are much, much, much, much poorer than you. That doesn’t seem fair.

So if you want to fly on a private plane, you should make sure that you’re doing something to take away that cost, at a minimum.

[Editor’s note: Taylor Swift reportedly offsets her flights with carbon credits, though it’s unclear exactly how the offsets are applied and whether her offsets (or anyone’s, for that matter) are effective.]

What do you think is the single most impactful thing a billionaire could do to address climate change?

They should invest in solutions. We need to bring finance to bear, fast, to build these companies to solve these problems. If you have billions of dollars, you can invest billions of dollars. Let’s do it in a way that makes you a bunch of money, but let’s do it.

A lot of people say they want to do the right thing. Okay, do the right thing.

You and your wife plan to give away the majority of your wealth as part of the Giving Pledge. As some of my colleagues have reported, billionaires giving away large chunks of their fortunes sounds great on paper, but many are still making billions, potentially, in industries or in ventures that are not great for the climate or the world. How, if at all, can that process be better?

I think the point about the Giving Pledge is that you recognize that you didn’t earn all your money by yourself. That, in fact, all of society has conspired over a long period of time, with amazing sacrifices by people for hundreds of years, to produce an environment where people could make that much money.

I think it seems to me to be absolutely incumbent on everybody to realize that they didn’t earn that money by themselves. Millions and tens of millions and hundreds of millions of people sacrificed for hundreds of years to build that framework. And so they, in effect, own part of what you have.

From my standpoint, the idea of giving back to society and recognizing that we’re all part of this together, and always have been—that’s a big point about this book, is we need to do this together. That’s the point of the Giving Pledge to me. To recognize, you’re not separate. You didn’t do it. It’s not yours. It’s all of ours. We have a responsibility to each other. Everybody. Not just billionaires, but everybody.

You end the book with an anecdote about your adult daughter, who was worried about bringing children into a world plagued by climate change. You tell her that having kids is the “ultimate statement of optimism.” Can you tell me more about what you meant by that?

I think that having a kid means that you believe that we’re going to pass on a world that is not just habitable, but is wonderful. We’re saying, “Our kids and our grandkids are going to live in a world that’s better than the one we were born into.” And we’re gonna do it. I really believe it. We just have to apply ourselves.

People often think that there’s a conflict between being optimistic and knowing we have a real problem. We do have a real problem. Of course we do. But that doesn’t mean we can’t and won’t solve it.