Ephemeral streams in Chinle Valley, ArizonaMarli Miller/Getty

Last year, in one of the most significant environmental legal cases in recent history, the Supreme Court’s conservative majority severely limited the federal government’s ability to regulate waterways. By narrowly interpreting the Clean Water Act as only applying to “relatively permanent, standing, or continuously flowing bodies of water” and wetlands with a continuous surface connection to those bodies, the court effectively cut federal protections for more than half of the country’s wetlands. Around 90 million acres of marshy areas are now much more vulnerable to pollution.

Scientists knew immediately the consequences of the case, Sackett v. EPA, would be massive—one plant biologist I spoke to last year who’d devoted her retirement to protecting wild Venus flytraps called it “the worst thing that’s happened in my conservation life.” But determining how the decision would impact the country’s vast network of rivers, lakes, and streams would take time and some scientific digging.

More than half of the water in the US’ major rivers originates from ephemeral streams.

Now, a year later, some of that research is trickling in: A new study from researchers at Yale and the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, published in Science last week, reveals why removing federal protections for some non-permanent waters could have a huge effect on the nation’s rivers.

The study focused on short-lived streams, fueled by rain or snow, called “ephemeral streams,” which the Sackett decision now excludes from federal protection under the Act. When an ephemeral stream is not flowing with rainwater, lead author and recent Yale postdoc Craig Brinkerhoff explains, it may look something like a dry riverbed. That may not sound like much, but according to researchers, more than half of the water in the United States’ major rivers originates in this type of stream. About 51 percent of water flowing through the Mississippi River in a given year, for instance, traveled through an ephemeral stream first. In the Columbia, it’s 52 percent. And for much of the Rio Grande, it’s more than 90 percent.

“So often, when we talk about rivers, we think of this specific line on a map,” says Boyce Upholt, a journalist and author of the recent book The Great River: The Making and Unmaking of the Mississippi. “That’s a really limited way of thinking about rivers.”

If regulators wished to protect rivers from pollution, it might make sense to regulate pollutants in ephemeral streams, too. But since these riverbeds are sometimes dry, they don’t qualify as “permanent, standing, or continuously flowing.” That’s why the Sackett decision is so devastating: With the authority of the Clean Water Act, the federal government can regulate pollution directly entering rivers and lakes. But now it has little jurisdiction over pollution entering the occasionally wet riverbeds upstream from them.

Conservationists are especially alarmed by the decision because they say there’s plenty of evidence to show that the Clean Water Act works. In the more than 50 years since Congress passed the Act, waterways are less polluted with contaminants like fecal bacteria (often, from sewage) and “suspended solids” including dirt and sediment than before, according to one 2018 mega-analysis.

The Science paper, notably, addresses Sackett head-on. “Our findings show that ephemeral streams are likely a substantial pathway through which pollution may influence downstream water quality,” helping reveal “the consequences of limiting US federal jurisdiction” over these waterways, the authors write.

When Brinkerhoff first started looking into mapping ephemeral streams as a PhD student at UMass Amherst, the endeavor was purely scientific. While researchers have long known ephemeral streams were ubiquitous, the waterways’ importance downstream had been murky. “If these things are hydrologically connected [to rivers],” Brinkerhoff wanted to know, “and if they’re everywhere, how big of an influence do they actually have?”

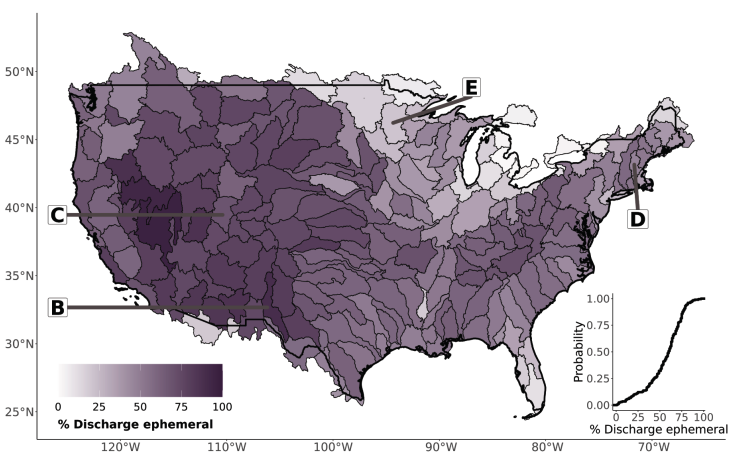

Brinkerhoff and his colleagues built a massive, high-resolution map of them, using maps from the US Geological Survey and pre-existing global groundwater models. They calculated that an average of 59 percent of the country’s river systems, by length, are ephemeral. This largely tracked with previous global estimates, Brinkerhoff says, but most interesting to him was that the trend held in Eastern states, which are typically wetter and more humid than in the West. “We don’t normally think of these places as having a lot of ephemeral streams,” he says.

Some 55 percent of the water that flows through the country’s major river systems, the researchers found, likely touched an ephemeral stream first. (Brinkerhoff says more research is needed to understand how climate change will impact these water systems.)

In 2022, after the Supreme Court agreed to take up Sackett, Brinkerhoff and his team realized the research could have even bigger implications. At the heart of the case was a question over what type of waterways ought to count as “waters of the United States” and would be subject to regulation. Brinkerhoff teamed up with policy researchers at Yale who could help translate the significance of their data for policymakers tasked with responding to the Supreme Court’s decision.

But midway through the peer review process, Sackett came down. To comply with the decision, the Biden administration then issued new regulations excluding ephemeral streams from coverage under the Clean Water Act. In October, House Democrats introduced a bill to undo the changes made under Sackett, but “the odds are against it” passing in a divided Congress, says Douglas Kysar, an environmental law expert and professor at Yale Law School and an author on the Science paper.

Kysar hopes this study on ephemeral streams may help policymakers craft better water policy. “All of us would agree that we hope it gets into the hands of decision-makers and their staff,” he says.

But the pathway for science to help inform policy is getting “narrower,” he says, particularly after several Supreme Court cases this term undermined regulatory authority, including the decision to overturn a 40-year-old legal precedent called “Chevron deference” that instructed judges to defer to agencies when interpreting vague statutes. “We really have a court that is aggrandizing power for itself and the federal judiciary,” Kysar says.

“What we saw in Sackett was the court using abstract, detached, unscientific reasoning.”

He sees Sackett as a kind of preview for how federal judges might handle future environmental cases—on wetlands, ephemeral streams, or any other issue. “What we saw in Sackett was the court using abstract, detached, unscientific reasoning,” Kysar says. “It paid essentially no deference to the experts at the EPA, the hydrologists, all the people who actually understand how ecosystems work and how pollution operates.”

And now, after the court’s Chevron ruling this term, federal judges largely won’t need to defer to agency experts at all—let alone university scientists who study ephemeral streams.