Dave Gilson

Last week, the University of Illinois’ College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences (ACES) in Champaign-Urbana made a momentous announcement: it has accepted a $250,000 grant from genetically modified seed/agrichemical giant Monsanto to create an endowed chair for the “Agricultural Communications Program” it runs with the College of Communications.

The university’s press release quotes Monsanto’s vice president of technology communications giving a taste of its vision for the investment:

With the population expecting to reach 9 billion by 2030, farmers from Illinois and beyond will be asked to produce more crops while using fewer resources. At Monsanto we are committed to bringing farmers advanced ag technologies to help them meet this challenge. Effectively communicating farmers’ efforts to feed, clothe and fuel a rapidly growing population is a major part of the solution.

A cynic might translate that statement this way: In order to maintain our highly profitable and hotly contested business model, we’ll need a new generation of PR professionals to construct and disseminate our marketing message.

Monsanto’s latest gift isn’t its first dalliance with the prestigious college, which is located in a city surrounded by millions of acres of fields planted with Monsanto’s GMO corn and soy seeds, both treated with regular doses of the company’s Roundup herbicide. Back in 2002, Monsanto donated $200,000 to ACES for the Monsanto Multi-Media Executive Studio, to be “used by faculty and staff of the college for presentations and seminars and for conferences involving companies and organizations with ties to the college and its mission.”

Nor is Monsanto the only gigantic food and ag company bestowing cash upon ACES. A cursory look at the college’s web site turned up a recent paper touting a novel infant formula that “boosts babies’ immunity”—funded by Nestle Infant Nutrition and co-authored by a researcher in its employ.

Then there’s this study, also by ACES researchers, which purports to show that soy protein “alleviates symptoms of fatty liver disease.” It’s brought to you by grants from the agribiz-aligned Illinois Soybean Association and Solae, a joint project of agrichemical giants DuPont and Bunge that calls itself “the world leader in developing innovative soy technologies and ingredients for food, meat and nutritional products.”

The most remarkable thing about all of this is that it isn’t remarkable at all. A few weeks ago, I pointed to a great Chronicle of Higher Education article documenting how university animal-health research has become dominated by the pharmaceutical industry—and how the products that emerge from that process are much more about pharmaceutical industry profits than animal health. Now there’s this eye-opening new report from Food & Water Watch (FWW) that documents in painstaking detail how the food and agrichemical industries have transformed our national public agricultural research infrastructure into essentially an R&D and marketing apparatus for their industry. (Similar trends hold for other areas of science research, most prominently medicine.)

FWW reminds us how ag-research institutions like the University of Illinois started: as so-called land-grant universities, launched by the federal government on public land in 1862. The idea of the land grants was to generate agricultural research, funded by the federal government, that benefited society as a whole. And that’s pretty much how things went for the first century. “Well into the 20th century, seed-breeding programs at land-grant universities were responsible for developing almost all new seed and plant varieties,” FWW writes. It might have added that those varieties were public resources, not owned or patented by any company. Farmers were free to save them for the next season, and many did.

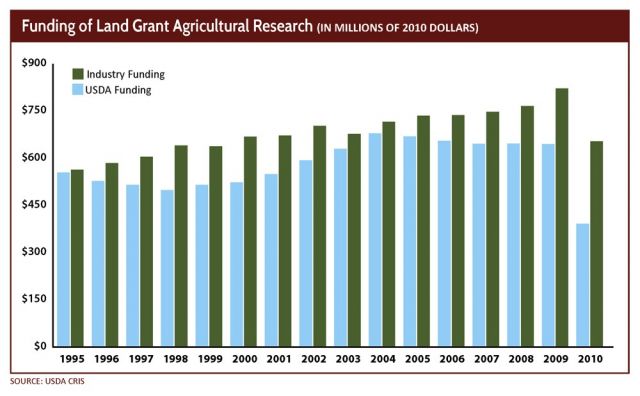

But then, starting in the 1980s, the federal government started to level off its investment in ag research—and meanwhile, after passage of the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980, began to encourage professors to behave like entrepreneurs who could benefit financially from their research, not public employees creating ideas for the public domain. That’s when food and agribusiness companies, which were then in the process of consolidating into the vast global enterprises we know today, began to funnel huge amounts of cash into the land grants.

By the early ’90s, industry funding had begun to outpace USDA research support for the land grants. And now, as fiscal austerity further pinches federal research funding, the gap between the industry and the USDA as land-grant paymaster has hit an all-time high. Here’s FWW:

Food & Water Watch

Food & Water Watch

And it’s not only research. Just as sports franchises have turned to corporate sponsors to fund stadiums, the land grants have turned to their agribiz benefactors for building funds, FWW found. At University of Minnesota, seed breeders toil in the Cargill Plant Genomics Building; while University of Missouri ag-science grad students attend seminars in the Monsanto Auditorium. Iowa State undergrads lounge in the Monsanto Student Services Wing; and food-science researchers at Purdue can bounce between the Kroger Sensory Evaluation Laboratory and the ConAgra Foods, Inc. Laboratory.

And all of this cash buys more than just symbolic power. In addition to landing their names on buildings, agribiz giants also “?ll seats on academic research boards and direct agendas,” the report shows. At Iowa State University, reps from the agribiz-aligned Iowa Farm Bureau and Summit Group, an industrial-scale producer of hogs and cows, have won seats on the governing Board of Regents. The report brims with examples of agribiz employees occupying seats on advisory boards of various ag-related centers within the land grants. My favorite is the way the University of Georgia’s Center for Food Safety forms its advisory board. Get this, from the center’s web site:

We invite food processing and related companies who are not presently members of the Center for Food Safety to join more than 40 food processors who are actively involved in the Center’s programs. There are different ways in which you can be involved with the Center. You may want to become a member of the Center’s Board of Advisors. The role of the Board is to provide input on food safety research needs of the industry. In addition, the Board provides suggestions on unique (not routine) opportunities/services the Center can offer to industry. For example, Center faculty can offer specialized workshops on food safety and quality issues or training on advanced equipment and techniques. A $20,000 annual contribution to the Center entitles a company a seat on the Board. [Emphasis added.]

Companies that have taken the center up on its offer include Cargill, Kraft, Hormel, Kellogg’s, Unilever, Earthbound, and McDonald’s.

Sometimes, compliant administrators are rewarded generously for their work. Monsanto tapped South Dakota State University president David Chicoine for its own board of directors in 2009, FWW reports. According to Inside Higher Education, Chicoine stood to make more from Monsanto in his first year on the board than he did from his state job. It gets better:

Weeks before Chicoine joined Monsanto, the company sponsored a $1 million plant breeding fellowship program at SDSU. Chicoine’s appointment at Monsanto also coincided with a new SDSU effort to enforce university seed patents by suing farmers for sharing and selling saved seed.

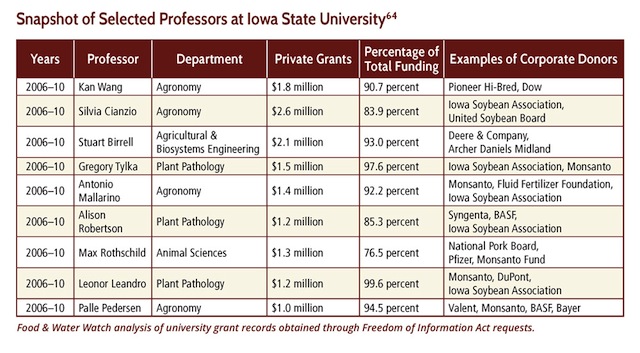

At some of the more prestigious schools, professors have morphed into something that looks a lot like house researchers for the agrichemical industry. Check out this snapshot from Iowa State. Using the Freedom of Information Act, Food and Water Watch analyzed the grants received by a selection of professors between 2006 and 2010, and calculated what percentage of their grants came from private sources. Here’s what they found: The corporate sector’s generosity might be commendable if it produced research that benefitted the public as a whole—such as new open-source seed varieties that are well adapted to organic ag, or techniques for rotating cattle and crops on land that improve soil and reduce fertilizer use. But that’s not what’s happening, FWW shows. Instead, the companies are funding strings-attached research that serves their own narrow interests. The report cites numerous studies to show this, and several concrete examples like these two:

The corporate sector’s generosity might be commendable if it produced research that benefitted the public as a whole—such as new open-source seed varieties that are well adapted to organic ag, or techniques for rotating cattle and crops on land that improve soil and reduce fertilizer use. But that’s not what’s happening, FWW shows. Instead, the companies are funding strings-attached research that serves their own narrow interests. The report cites numerous studies to show this, and several concrete examples like these two:

When an Ohio State University professor produced research that questioned the biological safety of biotech sun?owers, Dow AgroSciences and [DuPont’s] Pioneer Hi-Bred blocked her research privileges to their seeds, barring her from conducting additional research. Similarly, when other Pioneer Hi-Bred-funded professors found a new [genetically engineered] corn variety to be deadly to bene?cial beetles, the company barred the scientists from publishing their ?ndings. Pioneer Hi-Bred subsequently hired new scientists who produced the necessary results to secure regulatory approval.

To be sure, while corporate cash has come to dominate university ag research, the USDA still funds a substantial amount of it: more than $300 million (vs. about $600 million from industry) in 2010. In addition to its research grants for land-grant professors, the agency also employs its own scientists and maintains its own labs; its total research budget stands at about $2 billion per year. Yet rather than act as a counterweight to the corporations, the USDA essentially mimics them. It “prioritizes commodity crops, industrialized livestock production, technologies geared toward large-scale operations, and capital-intensive practices,” FWW shows.

Here’s a startling example: the USDA dedicates more money to research on sweetener crops like sugar beets ($18.1 million per year) and oilseed crops ($79.4 million) than it does to nutrition education ($15.5 million).

Such expenditures of public cash help sweeten the fortunes of the food and agrichemical industries, but foretell a bitter harvest for society as whole.