Meet the Vintons, a ranching family in the Sandhills region of northeast Nebraska. Last week I spoke to Sherry, the smart, friendly matriarch of the family (in red). She began ranching 30 years ago, shortly after marrying her husband Chris (in brown), whose family has worked this land for five generations. Today, Sherry and Chris run the operation with help from their two grown children and their spouses. Their youngest daughter (front and center) is in college.  Photo appears courtesy of the Vinton family

Photo appears courtesy of the Vinton family

So far this year, the Vintons’ ranch has received less than two inches of rain. In a typical year, it would have gotten eight or nine by now. When I asked Sherry to describe the difference between a typical year and this drought year, she sent me a set of photos taken by one of her daughters. Here’s a view of her pasture from August 2007:

Photo by Jessica Vinton TaylorAnd this photo of the same pasture was taken this summer:

Photo by Jessica Vinton TaylorAnd this photo of the same pasture was taken this summer: Photo by Jessica Vinton Taylor

Photo by Jessica Vinton Taylor

The Vintons’ ranch is a cow-calf operation, which means that they keep a herd of mother cows who give birth to beef calves. All told, the Vintons have about 1,500 head of cattle, though the number varies. In a good year, most of the mother cows will give birth to calves in the spring. The Vintons will keep the young calves around till the following September, by which time they’ll have gained enough weight to fetch a good price; a good slaughter weight is about 1,200 pounds.

But in order to gain that weight, the young calves need to eat a lot, either on pasture or in feed composed of hay, corn, and other grain. In a drought year, pasture is scarce, and grain is expensive. In drought years, keeping the calves around until they reach market weight isn’t cost effective, since it costs so much to feed them. It’s also important to keep enough grass for the mother cows so that they’ll continue to be healthy and productive in the long term.

So all winter and spring, it’s a guessing game: Will the drought end in time for the rancher to be able to afford to keep the mother cows healthy and the babies growing? Or will they have to sell some so that the remaining animals have enough to eat? And if they do keep them around, will they be able to afford feed once the pasture is gone?

This year for the Vintons, unfortunately the answer was pretty clear. “This drought is so widespread that it is going to be difficult to find feed,” Sherry told me. “And feed is very expensive.” Already the Vintons have sold three truckloads of cattle to ranchers in Texas who haven’t been hit as hard by the drought. Some of the animals they sold were pregnant cows—a tough decision, says Sherry, since they lose money both on the cow and the calf it would have given birth to. As for the yearling calves, by selling them now instead of in September, they’ll lose about $350 per animal. Sherry estimates that before the drought is over, they’ll have to reduce their herd size by 43 percent. “And it could be worse than that,” she says. “We have a pretty good sense that this is going to extend through October. There is no relief in sight.”

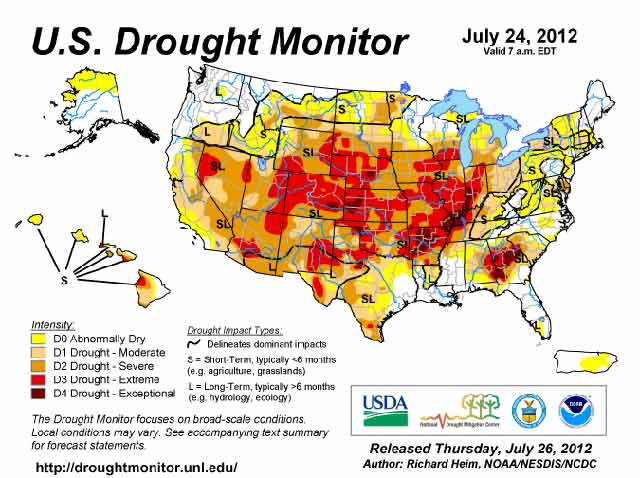

There’s a lot of guesswork that goes into making these decisions. But weather forecasts and news about the droughts in other regions help a lot. In earlier years, Vinton told me, she and her husband relied on predictions in monthly farming publications. Now they use this web-based map from the US government that allows them to see conditions all across the United States (an interactive version is here):

The US Drought Monitor is a partnership between the National Drought Mitigation Center, United States Department of Agriculture, and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Map courtesy of NDMC-UNL.

The US Drought Monitor is a partnership between the National Drought Mitigation Center, United States Department of Agriculture, and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Map courtesy of NDMC-UNL.

Sherry has been through other tough years: ’88, ’95, and ’02 were all very dry. But nothing as long-lasting or widespread as this. “This drought has become very severe very fast,” she says. “That’s one of the things that’s different about it.”

David Anderson, a livestock economist with Texas A&M University’s ag extension, agrees: This year is drier and hotter than anything he can remember. “As this drought gets worse, where can those cows go?” says Anderson. “There is no place for them to go but to slaughter.” Anderson notes that slaughtering decisions can have long-term consequences. Conception rates among mother cows are typically lower in the year following a drought. What’s more, ranchers spend a lot of time and resources perfecting the genetics of their herd—ensuring that the mother cows are bred to be productive and the steers to yield high quantities of valuable meat. If ranchers have to send a large portion of their herd to slaughter, they lose valuable breeding resources.

Of course, all this affects the price of beef. Last week, the Climate Desk’s James West reported that many foods—milk, eggs, chicken, and bread—will become more expensive in the coming months because of the drought. Interestingly, says Anderson, beef prices will actually take a nosedive in the short term—say, through September. Since so many ranchers are being forced to sell their cows right now, the market will be flooded with beef. But after that, there will be a scarcity, so the prices will rise again.

So should you buy beef to support the ranchers through the drought? It’s a really tough question. From a purely environmental standpoint, the answer is probably no. In terms of energy use, emissions, and waste production, beef—especially the conventionally raised kind—has a bigger footprint than almost any other meat. Hardline environmentalists recommend against eating any beef at all.

But I think it’s more complicated than that. As I wrote in this column a few years back, grazing animals, if managed correctly, can actually enhance the land. Unfortunately, the way the beef industry is structured now, most ranchers can’t afford to keep their animals on pasture for their entire lives. It’s simply too expensive. That said, ranchers like the Vintons put an enormous amount of time and effort into caring for the land—they have to, in order to ensure that their ranch is profitable in years to come. Without grass, there would be no cows.

The truth is that if droughts like this continue in the years to come, it’s going to be harder and harder for families like the Vintons to care for the land. Since pasture will become even more scarce, they’ll have to feed grain—which is much worse for the environment than grass. The evidence that recent droughts and heat waves are linked to climate change is piling up. As my colleague Kate Sheppard wrote recently, one study placed the odds of this year’s extreme heat happening without climate change at 1 in 1.6 million.

So to help ensure that droughts like this don’t become the new norm, the best thing you can probably do for America’s ranchers is to help curb climate change. Aside from that, you can buy American beef rather than the cheap imports from South America, which tend to drive prices down.

In the meantime, Sherry and her family will be closely monitoring the drought map and hoping that this year’s dry weather finally gives way to rain, she says. “I’d be lying if I didn’t say this made me nervous about providing for our family.”