<p><a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?lang=en&search_source=search_form&search_tracking_id=BNoBNn1EE9TsraFpdIytTA&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&searchterm=newspaper&search_group=&orient=&search_cat=&searchtermx=&photographer_name=&people_gender=&people_age=&people_ethnicity=&people_number=&commercial_ok=&color=&show_color_wheel=1#id=127408157&src=uKZHRwFCPT_hf_Zs9YrioQ-1-1" target="_blank">RTImages</a> and <a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?searchterm=evil+corn&search_group=&lang=en&search_source=search_form#id=76978777&src=Lo378xmUTRaC9Mj3IFK_6w-1-41" target="_blank">Xu</a>l/Shutterstock</p>

Ah, high summer. Time to read stories about the declining effectiveness of GMO-seed giant Monsanto’s flagship products: crops engineered to resist insects and withstand herbicides.

Back in 2008, I felt a bit lonely participating in this annual rite—it was mainly just me and reporters in the Big Ag trade press. Over the past couple of years, though, it has gone mainstream. Here’s NPR’s star agriculture reporter Dan Charles, on corn farmers’ agrichemically charged reaction to the rise of an insect that has come to thumb its nose at Monsanto’s once-vaunted Bt corn, engineered to contain the bug-killing gene of a bacteria called Bacillus thuringiensis:

It appears that farmers have gotten part of the message: Biotechnology alone will not solve their rootworm problems. But instead of shifting away from those corn hybrids, or from corn altogether, many are doubling down on insect-fighting technology, deploying more chemical pesticides than before. Companies like or that sell soil insecticides for use in corn fields are reporting huge increases in sales: 50 or even 100 percent over the past two years.

And this, from a veteran observer of the GMO-seed industry who—in my view—sometimes errs on the side of being too soft on it.

The Wall Street Journal’s Ian Berry got the ball rolling early this year with a May report bearing the evocative headline “Pesticides Make a Comeback: Many Corn Farmers Go Back to Using Chemicals as Mother Nature Outwits Genetically Modified Seeds”:

Insecticide sales are surging after years of decline, as American farmers plant more corn and a genetic modification designed to protect the crop from pests has started to lose its effectiveness. The sales are a boon for big pesticide makers, such as American Vanguard Co. and Syngenta.

All the attention on superinsects has taken the major-media spotlight off of the “superweeds” that have evolved to shrug off copious doses of Roundup, the herbicide that’s supposed to make Monsanto’s Roundup Ready crops immune to weed problems. But that doesn’t mean these thug weeds have stopped working their magic. They’re “gaining ground” in Iowa, heart of the US corn/soy belt, reports the Cedar Rapids-based Gazette. And farmers are responding just as they did in the South, where Roundup-resistant weeds have had been rampant for at least five years: with a chemical deluge. Here’s one of several anecdotes in the Gazette piece on that illustrate this familiar theme:

Tracy Franck, who farms 2,400 acres in Buchanan County with his dad and son, said they “are putting on more Roundup every year to kill the same amount of weeds.” They, like most other farmers in their area, are also applying a pre-emergent residual herbicide to help control the glyphosate [the active ingredient in Roundup]-resistant weeds that are just beginning to show up in their fields. “We are starting to see some lambs quarter and giant ragweed that are tough to kill,” he said.

(As someone who likes to eat lamb’s-quarter, a delicious, nutrient-dense green, I’m sorry to see it emerge as a target of chemical warfare.)

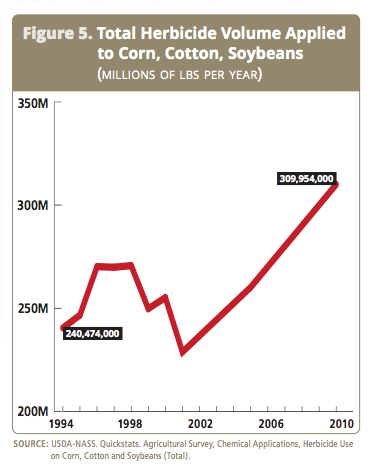

Meanwhile, Food and Water Watch has just come out with a damning report called “Superweeds: How Biotech Crops Bolster the Pesticide Industry.” The nutshell: The rise of Roundup Ready corn, soy, and cotton in the mid-1990s has given rise to a boom in use of herbicides. Note how use fell for a while after the introduction Roundup Ready seeds before beginning to spike in 2001, when Roundup resistant weeds began to emerge.

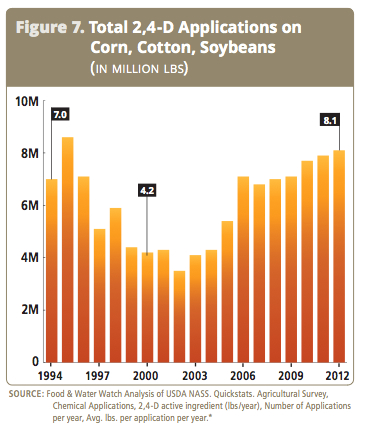

GMO industry defenders point out that relatively benign Roundup at least displaced older, more toxic herbicides as farmers transitioned to Roundup Ready crops. But as FWW shows, that no longer holds. Farmers are turning to one particularly nasty old herbicide, 2,4-D, with a vengeance as Roundup loses effectiveness:

All of which raises the question: If Monsanto’s seeds are failing, why are farmers still buying them in such vast numbers? Part of it is surely habit—for farmers, it must seem easier to plant Roundup Ready corn and supplement Roundup with a harsher herbicide than to try a whole new weed-control system.

The answer may also at least partly lie in the GMO seed giants’ dominance of the seed market. Last year, the US Department of Justice unceremoniously halted its antitrust investigation of Monsanto and its peers without taking action. As I showed in my post at that time, Monsanto, DuPont, Syngenta, and Dow together control 80 percent of the corn seed market and 70 percent of the soy market. In such tightly consolidated markets, you get stuff like this (from my post from last year):

There’s also evidence that farmers lack access to lower-priced [non-GM] seeds. In 2010, University of Illinois researcher Michael Gray surveyed farmers in seven agriculture-intensive counties of Illinois. He asked them if they had access to high-quality corn seeds that weren’t genetically modified to contain Monsanto’s Bt insecticide trait. In all seven counties, at least 32 percent of farmers said “no.” In one county, 46.6 percent of farmers reporting having no access to high-quality non-Bt seed. For them, apparently, they had little choice but to pay Monsanto’s high prices for Bt seeds, whether they needed them or not.

At any rate, as Food and Water Watch notes, the withering of herbicide-tolerant and Bt-infused crops hasn’t hurt these companies at all—indeed, they also sell pesticides, and as NPR and the Wall Street Journal report, pesticide sales are booming.