<a hrefhttp://www.shutterstock.com/pic-81523939/stock-photo-crop-duster.html?src=6PJicb6aDXn8NCBXhYAlAg-1-2">Dale A. Stork</a>/Shutterstock

Before pesticides go from the laboratory to the farm field, they have to first be vetted by the Environmental Protection Agency. But they’re commonly mixed—sometimes by the pesticide manufacturers, sometimes by the farmers themselves—with substances called adjuvants that boost their effectiveness (to spread more evenly on a plant’s leaf in the case of insecticides, or to penetrate a plant’s outer layer, allowing herbicides to effectively kill weeds). Despite their ubiquity, adjuvants aren’t vetted by the EPA at all; they’re considered “inert” ingredients.

I first wrote about them last year, when adjuvants mixed with fungicides came under suspicion of triggering a large bee die-off during California’s almond bloom. Recently, an eye-popping article by Purdue weed scientists in the trade journal Ag Professional brought them to my attention again. The piece illustrates the unregulated, Wild West nature of these additives.

In the article, the authors note that two companies are hotly promoting adjuvant products as a kind of miracle cure for the ever-increasing scourge of herbicide-resistant weeds. That’s a bold claim, given that resistant weeds now plague more than 60 million acres of farmland.

Odder still, both companies attribute their products’ effectiveness to nanotechnology, a controversial, lightly regulated engineering tool that leverages the fact that when you break common substances into tiny particles, they behave in radically different ways than they do at normal sizes. Nanoparticles are so tiny, their size is measured in nanometers—a billionth of a meter. (A human hair is about 80,000 nanometers thick; nanoparticles typically measure in at less than 100 nanometers.)

An adjuvant called ChemXcel, from a Minnesota-based company called C&R Enterprises, claims to “kill herbicide-resistant weeds” when mixed with common herbicides like glyphosate. It works its magic through “patented, proprietary nano-drivers” that “alter the glyphosate chemistry” by “coating the individual DNA gene-sequencing molecules internally,” the company claims.

Then there’s NanoRevolution 2.0, marketed by a company called Max Systems. When goosed with a bit of NanoRevolution 2.0, the company states, “the herbicide ‘piggybacks’ onto the nano particles as they penetrate the leaf structure, carrying the herbicide directly to the root system for a faster enhanced plant absorption of herbicides even on hard-to-control weeds.”

Taken aback by the claims and the use of nanotech, I contacted the EPA to see what, if anything, the agency had to say. “While we are not familiar with those particular products, EPA has jurisdiction over substances that meet the definition of pesticides, that is, claims are made for them that they kill, repel, prevent, or otherwise control pests,” an Environmental Protection Agency spokesperson wrote in an email. “As long as pesticide adjuvant products don’t make pesticidal claims, they are not pesticides and the components of adjuvants are therefore not pesticide ingredients (either active or inert)”—and thus not subject to EPA vetting. Manufacturers aren’t even required to list ingredients in adjuvants.

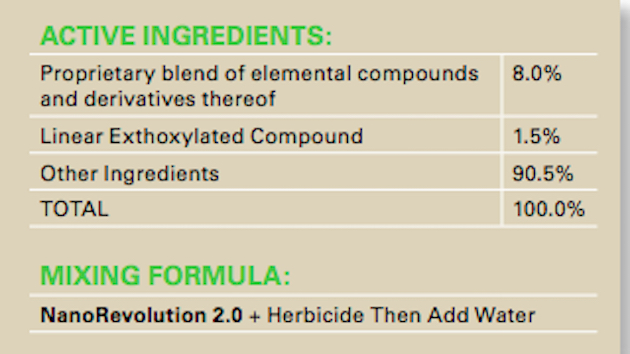

Here, for example, is Max Systems describes the ingredients of NanoRevolution 2.0:

Purdue weed scientist Bill Johnson, who co-authored the Ag Professional piece, says he and his team found that neither of these “nano” products work as advertised. “I began getting calls about reports that these things were being pushed in northern Indiana, and I thought, we need to prove or disprove the claims.”

So he and colleagues tested the products on a weed patch known to be glyphosate resistant, mixing them with glyphosate at levels recommended by the manufactures. The results, published in the trade journal Ag Professional, were underwhelming. On its own, Roundup (Monsanto’s version of the glyphosate herbicide) killed just 13.8 percent of weeds. Mixed with ChemXcel, it killed 15 percent of weeds, while the called NanoRevolution 2.0/Roundup mix killed 18 percent of weeds.

Johnson explained that herbicides are always mixed with adjuvants—they’re typically needed to help the herbicide penetrate a weed’s outer layer. But these particular ones perform no better or worse than conventional adjuvants on the market. But they don’t come anywhere near to solving the herbicide-resistance problem, as the companies claim to do.

C.J. Mannenga, co owner of C&R Enterprises, pushed back strongly on Johnson’s assessment and challenged his results. “We know our product works,” he said. “We’ve shown it in Georgia, we’ve shown in Ohio, we’ve shown it in Missouri, we’ve shown it in Iowa,” he said. When we spoke Tuesday afternoon, Mannenga told me that he was in Osborne, Kansas, about to “meet with a major [agrichemical] distributor” who is “extremely interested in the product … I’m going to do a demonstration to show them indeed it does work.”

While the product’s information sheet doesn’t list its active ingredients, he readily revealed it to me: “it’s just carbon nanotubes.”

Carbon nanotubes are one of the most controversial nanoparticles—often compared to asbestos for their ability to lodge into the lungs and cause trouble when they’re breathed in. This 2014 assessment by researchers at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell is hardly comforting:

Though ecosystem impacts remain understudied across the CNT [carbon nanotube] lifecycle, evidence suggests that some aquatic organisms may be at risk. While there have been significant advances in the regulation of CNTs in recent years, the lack of attention to the potential carcinogenic effects of these nanomaterials means that current efforts may provide a false sense of security.

Meanwhile, no one employed by NanoRevolution 2.0 maker Max Systems returned my request for comment.