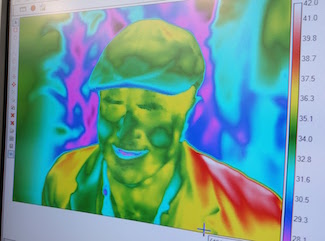

From left, Glenn Stone, Tom Philpott, and Robb Fraley at Monsanto’s Global R&D Headquarters Facility in St. Louis, April 2016

I normally cover the agrichemical industry from afar—parsing World Health Organization pesticide assessments, say, or analyzing megamergers. But on a recent afternoon, I found myself plunged into the industry’s very bosom: Monsanto‘s global R&D center in suburban St. Louis.

Alongside Washington University anthropologist Glenn Stone—whose undergraduate class on “brave new crops” I was in town to address—I spent five hours winding through the labyrinthine corridors of the vast facility, speaking with researchers, scientists, and managers from all five of the company’s “innovation platforms”: biotechnology, plant breeding, soil microbes, pesticides, and data science. Our long march through the building was bookended by interviews at a conference table with Monsanto’s chief technology officer, Robb Fraley, who’s an early innovator in genetically altered crops and a tireless defender of the controversial company.

In his classic 2001 book on the rise of Monsanto as an agribusiness titan, Lords of the Harvest, Dan Charles portrays Fraley as a ruthless figure. “He’s a really smart guy, but absolutely merciless,” a former Monsanto exec tells Charles. I found Fraley formidable: a barrel-chested man with a large bald head and a steady, skeptical gaze. But he was also unfailingly friendly and even occasionally light-hearted—we joked about our common baldness, and he expressed regret that he hadn’t donned a flat cap like the one I wore that day, “just to fit in.”

Monsanto once had a reputation as a tightly guarded company, but has made an effort in recent years to be more transparent. My entire visit was on the record, and Fraley and other Monsanto workers spoke freely. Here are some things I learned.

The company doesn’t seem too keen on old-school GMOs anymore. Fraley accompanied us to the biotechnology wing of the research center, the first stop on our tour. Strikingly, we didn’t hear a peep about the GM wonder crops that the industry used to claim were just around the corner: corn that grows well in drought conditions, say, or thrives with minimal amounts of nitrogen fertilizer. Instead, we heard vigorous defenses of a trait that Monsanto has been selling since genetically altered crops first hit farm fields in the mid-’90s: the insect-killing gene from the soil bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis, known as Bt.

A researcher from India described his childhood on a two-acre farm applying insecticides with a backpack sprayer—a hazardous activity made obsolete, he said, by the rise of Monsanto’s Bt cotton in India. Then the same researcher launched into the benefits of another crop—a soybean product now taking off in Brazil. It’s engineered to contain both the Bt insecticide and the other GM trait that Monsanto has been selling since the 1990s: resistance to glyphosate, the company’s flagship herbicide. In other words, during our stop at the biotech wing, we heard about nothing completely new, but rather about the same two traits Monsanto has been selling for two decades: herbicide tolerance and Bt.

Later, back at the conference table, Fraley gave a surprisingly sober assessment of GMOs for an executive who has spent his career promoting and defending them. He declared that classical plant breeding, sped up by genomic tools, is the “mainstay,” “base engine,” and “core” of Monsanto’s business, and stressed that it always would be, adding that it takes up half of the company’s R&D budget.

“When people think of us, they always think of Monsanto as the GMO company,” Fraley said. “I helped invent it [GM technology], and we’ve been the leader in that space,” he said. “But by far the biggest contribution we’ve made to yield gains around the world is how we’ve applied biotechnology to the [classical] breeding engine itself.”

Gene transfer is an expensive technology—”it costs us $150 million to develop a GMO product,” he said. “We only use it on things we can’t do any other way. The only way to get a Bt gene into a corn or soybean plant is to use gene-transfer technology and create a GMO,” he said.

Otherwise, Monsanto prefers to use classical breeding or seed treatments—pesticides that are taken up by the plant as it grows. I asked him whether GM technology could, as boosters used to insist, one day achieve grand visions like corn that mimics legumes and snatches nitrogen out of the air for self-fertilization. “Not likely,” Fraley said. He and his team have concluded that creating a nitrogen-fixing corn through gene transfer would require 30 separate traits, he said, and thus be way too costly.

But that doesn’t mean Monsanto is giving up on cutting-edge techniques. While downplaying the role of gene transfer, Fraley and other Monsanto employees embraced other genetic methods for altering crops: gene silencing, or RNAi (which I’ve discussed at length here), and gene-editing techniques, like the much-ballyhooed CRISPR-Cas9. Fraley declared these technologies “transformative” and took pains to classify them as variations on breeding, not GMO technologies. (Washington University’s Glenn Stone, who accompanied me on the tour, has more on this rhetorical effort here.)

Gene editing tools like CRISPR are a “superdirected” version of classical breeding. They “let you breed even faster and better, and allow you to do some of the things you can do [with GM technology], but won’t let you introduce a new trait,” he said.

As for RNAi gene-silencing technologies, Monsanto has plenty in the pipeline, Fraley added. There’s a corn product in the final stages of US Department of Agriculture and the Environmental Protection Agency vetting that contains RNAi matter that will target and kill specific crop-chomping insects, leaving everything else unscathed, he said (though this is not a universally held belief). He also pointed to an RNAi spray in the works that will silence the genes that allow weeds to withstand the glyphosate herbicide—adding new life to a key Monsanto product now losing effectiveness as weeds evolve to resist it.

Soil microbiota supplements are hot! (And they apparently go well with pesticides.) My favorite episode of our trip was our stop at Monsanto’s emerging soil microbial unit, which develops supplements meant to boost soil health and produce more robust crops.

“You have more microbial cells in you than you have your own cells,” a researcher explained. “A plant is no different—I guarantee there are more cells [in soil microbes] than there are in plants.” And so Monsanto is working diligently to identify and market the “most beneficial” of the microbes—ones that can help make nutrients more bio-available to crops, or crowd out soil-borne pathogens. And just like people can eat yogurt or take “probiotic” supplements to add beneficial microbes to their gut biomes, farmers can buy microbial seed treatments and sprays to fortify their soil, he said.

Now, I’m not someone who’s readily convinced that Big Pharma is going to come up with some magic probiotic mix that transforms human health; nor do I think Big Agrichemical is going to stumble upon and package just the right combo of microbe species for growing robust crops without lots of fertilizers and pesticides. The microbial communities that exist in animal guts and in the soil have evolved over eons. I suspect that diverse diets and crop rotations—not lab-grown potions—are key to engendering healthy biomes, both within our bodies and in the dirt.

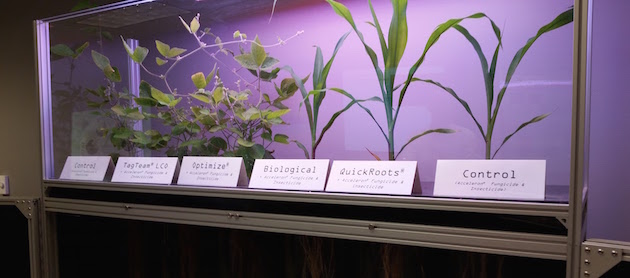

Still, I was happy to see Monsanto was thinking in terms of adding life to soil, not dousing it with chemicals designed to stamp out life. So what I saw next made my jaw drop. The researchers pointed to a glass case (below) featuring hearty-looking corn and soybean plants grown with microbial products already on the market, with placards featuring names like Control, Tag Team, Optimize, and Biological.

But for each of the six products, I noticed, the words “Acceleron® Fungicide and Insecticide” appeared under the product name. I cleared my throat and asked why “biological” products were being marketed under biocide labels. The researcher handled the question in stride. “What we’ve done is taken biological products and put it on top of the fungicides and insecticides most [corn and soybean] growers are using today,” he said.

Eventually, he said, they hope growers will begin to actually replace the chemicals with microbes. (In case they don’t, Monsanto seems to be hedging its bets—earlier in the tour, I had met people from the chemicals division who informed me that the company is also developing new fungicides.)

Later, I looked up the Acceleron product. It turns out it’s marketed by Asgrow, one of Monsanto’s seed subsidiaries. It’s a mix of pyraclostrobin, the potentially worrisome fungicide I wrote about last week, and Imidacloprid, a member of the neonicotinoid class of insecticides that’s suspected of harming bees, birds, and aquatic creatures.

As for the microbial mix the company mashes up with those potent chemicals: It’s made up of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, a common soil bacteria, and trichoderma virens, which is, yes, a fungus. So probably the most remarkable thing I learned on my trip is that Monsanto is marketing a fungus and a fungicide in the same package. (Presumably, that particular fungicide doesn’t kill the trichoderma virens fungus.)

Altogether, it was an informative and provocative visit. In addition to what I’ve chronicled here, I also learned about impressive non-CRISPR technology used to speed up good old classical breeding, and I had a fascinating conversation with Fraley and other executives about the data services Monsanto sells to farmers—topics I plan to explore in future posts.

And I greatly appreciated the access and transparency granted to me. In our conversations, Fraley repeatedly mentioned the importance of open dialogue between Monsanto and its critics, and I agree. I hope we can continue it.