Mother Jones; Ian West/PA Wire/AP

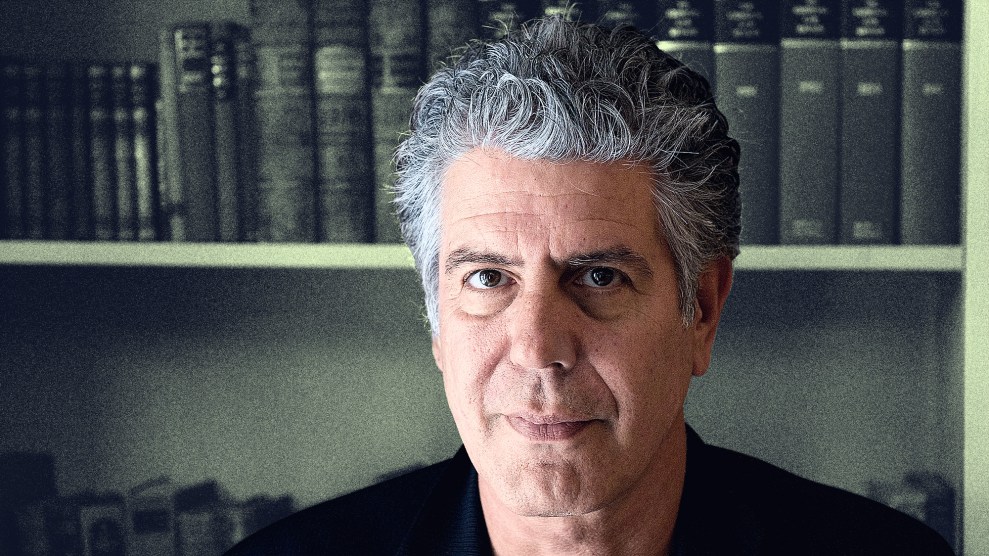

Anthony Bourdain is dead at 61. His body was found this morning in a hotel room in France, the country that inspired his work as a chef. He ended his life where he has lived it for so many years—on the road, producing his globe-trotting television show, a valentine to the world’s dizzying variety of foodways and the unsung people who maintain them.

One way to get an idea of how someone lived is to check in with the people he worked with. The US restaurant world, and the media constellation that surrounds it, was Bourdain’s milieu, from the start of his career as a junkie chef in lower Manhattan to his rise to fame as a tell-all author to his status as a global television star and culinary icon. And that world is in a state of sorrow and shock at news of Bourdain’s passing.

Back in 2010, one of history’s greatest fake Twitter accounts, @RuthBourdain, mashed up Bourdain with the former Gourmet editor and New York Times food critic Ruth Reichl. Soon after its launch, Bourdain gloriously lampooned Reichl, who edited him for a time at Gourmet, for her flowery Twitter style, which he dubbed the “Dao of Ruth.” Here’s audio:

Reichl took the ribbing with great humor (she phones in to join the above hilarity). And here’s her reaction to her old friend’s death:

Oh Tony. Oh no. Sitting here weeping. There will never be another like you. Really tragic loss.

— ruthreichl (@ruthreichl) June 8, 2018

And here’s Micheal Ruhlman, ace cookbook writer and Bourdain collaborator:

Absolutely stunned. @Bourdain you motherfucker. You giant. You friend. You writer. You most loyal to all around you. God, I’m so sad. Oh, this world. We’ve lost a hero.

— Michael Ruhlman (@ruhlman) June 8, 2018

José Andrés, the Spanish-born Washington DC chef and prominent Trump critic:

My friend..I know you are on a Ferry going to somewhere amazing…..you still had so many places to show us, whispering to our souls the great possibilities beyond what we could see with our own eyes…you only saw beauty in all https://t.co/Ltw9HrCBb2 will always travel with me https://t.co/Yv4Ntud6X0

— José Andrés (@chefjoseandres) June 8, 2018

Israeli-born UK chef and cookbook master Yotam Ottolenghi:

Celebrated US restaurateur/chef David Chang, who published Bourdain often in his late, lamented ‘zine Lucky Peach.

This list could go on forever; foodie Twitter is abuzz with such laments and tributes.

I adored Bourdain’s work for two reasons, beyond his obvious charisma and savage writing chops. As someone who worked the grill at a busy Texas steakhouse for seven years starting at 16, I devoured his landmark 2000 book Kitchen Confidential, a ribald account of what happens in the shadows of the restaurant trade. Few authors have so perfectly described life on what’s known as “the line” as well.

So who the hell, exactly, are these guys, the boys and girls in the trenches? You might get the impression from the specifics of my less than stellar career that all line cooks are wacked-out moral degenerates, dope fiends, refugees, a thuggish assortment of drunks, sneak thieves, sluts and psychopaths. You wouldn’t be too far off base. The business, as respected three-star chef Scott Bryan explains it, attracts ‘fringe elements’, people for whom something in their lives has gone terribly wrong. Maybe they didn’t make it through high school, maybe they’re running away from something-be it an ex-wife, a rotten family history, trouble with the law, a squalid Third World backwater with no opportunity for advancement. Or maybe, like me, they just like it here.

In that book, Bourdain dug deep to get at the cook’s glory and pain: the relentless heat, the sharp knives, the splattering fat, the endless tap-tap-tap of the machine spitting out orders, the clash of egos and tempers, the resort to alcohol and other substances for relief—but also the ineffable camaraderie one finds in those fiery trenches and that remains a treasured memory for me to this day. The only accounts I know that equal Kitchen Confidential are Orwell’s notes from the dish-room underground in Down and Out in Paris and London, which Bourdain loved; and The High Bonnet, Idwal Jones’ 1945 novel of life in Parisian kitchens, which Bourdain rescued from obscurity by adding a great introduction to a 2001 reprint.

Of course, the world Bourdain described is hyper-masculine, and as the fantastic food politics journalist Tracie Macmillan told me in a recent interview for Bite podcast, Kitchen Confidential glorified a “rough-and-tumble, no-rules-apply culture in kitchens,” largely centered on male sexual exploits. In her analysis, the message delivered is: “To be an authentic chef, to be a chef’s chef, you have to be someone who objectifies women.”

Not long after, Bourdain came out with a statement supporting women in the restaurant world who were coming forward with stories of harassment, and worse, from some of the biggest names in the US food world. And he addressed criticisms of the gender politics in his famous book:

To the extent which my work in Kitchen Confidential celebrated or prolonged a culture that allowed the kind of grotesque behaviors we’re hearing about all too frequently is something I think about daily, with real remorse.

In that piece, he also denounced his old friend Mario Batali, the mega-celebrity chef, over mounting allegations of sexual misconduct.

And that brings me to the second reason I loved Bourdain’s work: He used the enormous reach and cachet he amassed to stick up for the marginalized and poke the eyes of celebrated goons—from Batali to former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. He spoke up often, from the Kitchen Confidential days to the present, for immigrant restaurant workers. In his hit CNN show Parts Unknown, he prided himself on straying from the Michelin Guide path and discovering and documenting culinary pleasures among ordinary, often marginalized people.

“Many in immigrant communities throughout the United States appreciated the ways in which he shed a humanizing light on their home countries,” Yousef Munayyer, Palestinian-American writer and executive director of the US Campaign for Palestinian Rights, told me. “This obviously became so much more important in the Trump era.”

In his famous episode on Israel, he gravitated to the occupied territories in Gaza and the West Bank, shining a light the harsh conditions faced by Palestinians as well as some wonderful cooking. His episode on Congo probably gave many Americans their first-ever exposure to Leopold, the 19th century Belgian king whose acts of colonial terror still haunt that region.

He could have enjoyed just as much celebrity and wealth—maybe more—without taking on such subject matter. He could have just been a foul-mouthed foodie savant, merrily on the prowl for the next great bite or sip.

It’s impossible to fathom the pain that drove him to end such a swashbuckling life. But there’s plenty to learn from the way Bourdain lived.