Here in the United States, 18 percent of people live in poverty. For particularly vulnerable groups like children and the elderly, the poverty rate exceeds 20 percent. Annie Lowrey, an economics writer for The Atlantic and author of the new book Give People Money: How a Universal Basic Income Would End Poverty, Revolutionize Work, and Remake the World, says poverty is a choice. But she doesn’t mean it the way US conservatives do—that poverty represents a failure of personal initiative.

“In the United States, we choose—I like to use the word choose—to let a huge number of people remain in very deep poverty,” she told me in an interview for the latest episode of Bite podcast. “Our safety net is designed that way, it is an inevitable outcome that you have a large number of people, including millions of children, who are impoverished.”

In Give People Money, she uses extensive on-the-ground reporting and deep dives into economic research to make the case for a universal basic income—a monthly cash stipend for every American, regardless of income or employment status. She argues that the US welfare system “has its roots in Elizabethan England,” where an “obsession with differentiating the deserving from the underserving poor”—the latter of whom were subjected to whippings and incarceration. Here in the United States, this “Puritanical” view of poverty “married with our country’s deep sense of individualism and our cult of self-reliance” to create a society quite tolerant of poverty, culminating in the unchecked plague of deprivation that was the Great Depression.

In response, the New Deal and President Lyndon Johnson’s 1960s-era War on Poverty created a fairly robust welfare state, but it has withered in the decades since as the old Puritanical/individualistic tendencies have regained political traction. Lowrey shows that the US safety net is now stitched together with a tangled array of programs that significantly reduce poverty but still allow millions of people, many of them children, to live in destitution.

The government’s main food-aid effort, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), is a perfect example. “SNAP is huge and really important to lifting people out of poverty,” she told Bite. “But it’s difficult to apply for and use.” Eligibility requirements are strict—for a family of four, gross monthly income can’t exceed $2,665, or about $32,000 per year. Adults have to comply with a work requirement and time limitations, and enrollment is “not automatic, even for families with kids,” Lowrey notes.

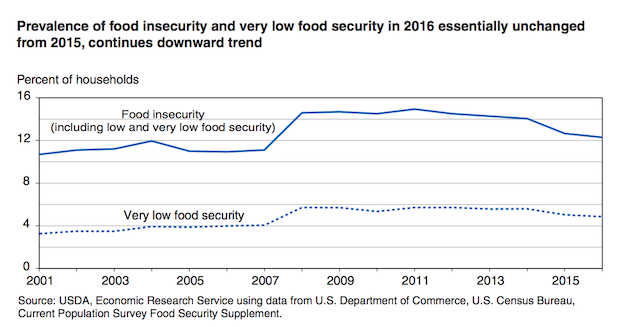

As a result, in 2015—the most recent year with government data—just 83 percent of Americans who met SNAP’s eligibility tests were enrolled in the program, and for the working poor, the participation rate was even lower: 72 percent. Thus despite annual spending of between $53 billion and $80 billion on SNAP, more than 15.6 million US households, including 3.1 million with children, “have difficulty at some time during the year providing enough food for all their members due to a lack of resources,” to use the US Department of Agriculture’s definition of “food insecurity.” Here are the latest USDA numbers in chart form:

For the book, Lowrey spent time with people who have slipped through the porous safety net. “Over and over again,” she writes, “these people on the edge stressed how poverty itself prevented them from getting out of poverty.” Payments from government programs were sometimes “far too parsimonious, failing to provide any real boost to the living standards of their recipients”; while others were “too confusing for the very poor to access.”

A universal basic income, of, say, $1000 per month for every American adult could go a long way toward reducing the toll of food insecurity, Lowrey said on Bite.

There is, of course, the contentious question of how to pay for such a program. In economic circles, there’s a robust and unsettled debate about whether what Lowrey calls a “full-fat,” universal basic income would trigger an economic boom that lifts millions out of poverty or drown the nation in debt. On Bite, Lowrey pointed out Republicans recently passed a $1 trillion tax cut without any regard for impact on the federal debt—and so far, it has had little or no impact in interests rates, the bogeyman of fiscal hawks.

“It’s a matter of morals,” she said. “What if you took away Donald Trump’s tax cut and instead you gave that money to to impoverished kids and centered them in the conversation?”she said. “It’s not businesses that need our help—they’re actually as profitable as they’ve ever been—it’s kids, it’s low income families, it’s working class families, it’s middle-income families that are still kind of struggling.”