Young hogs in a confinement in Farmville, NC. Gerry Broome/AP

While Hurricane Florence’s floodwaters rise on North Carolina’s coastal plane, inundating massive hog and poultry farms, the question arises: Why on earth would the meat industry alight upon such flood-prone territory in the first place?

After all, last week’s mega-storm comes hot on the heels of the similarly destructive Hurricane Matthew in 2016. Back in 1999, after another epic hurricane, Floyd, “floodwaters flushed the contents of fuel tanks, pig waste lagoons, and human sewage treatment plants into the state’s rivers and sounds and, ultimately, out into the Atlantic Ocean,” NASA’s Earth Observatory reported. “The carcasses of pigs, chickens, and other dead animals floated in the soup of pesticides, fertilizer, and topsoil carried in the massive runoff.

A new paper from Duke University researcher sketches out an answer to the riddle of the the industry’s fixation on such a risky region. Short summary: Residents of the area tend to have lower incomes—and are more likely to be black and Native American—than other parts of the state. In other words, the results suggest, the industry has parked itself in an area populated by marginalized people with few resources to defend themselves against environmental threats.

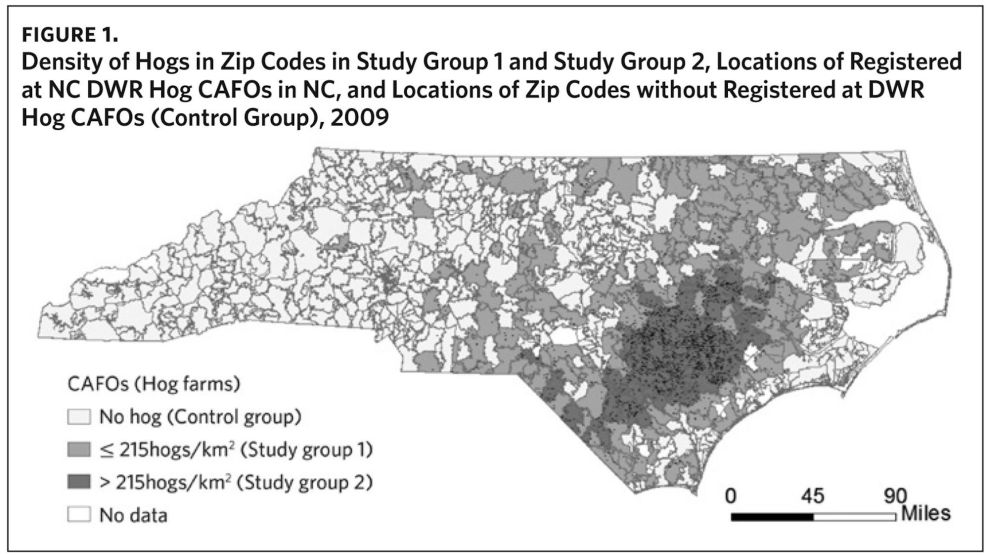

The Duke team broke North Carolina’s zip codes into three groups, after excluding urban areas with populations greater than 50,000: those with with at least some large-scale hog production (Group 1), those with high concentrations of hogs (Group 2), and those with none (control).

The proportion of African-American residents was nearly 50 percent higher in zip codes with at least some hog production vs. the control (28.8 percent vs. 19.3 percent); while the American Indian population was three times as dense (2.4 percent vs. 0.8. percent). The hog regions were also significantly poorer, with annual incomes averaging $39,005, vs. $46,414 in the control area.

These results track with a 2014 paper by University of North Carolina researchers finding that “the proportions of Blacks, Hispanics and American Indians living within 3 miles of an industrial hog operation are 1.54, 1.39 and 2.18 times higher, respectively, than the proportion of non-Hispanic Whites.”

The new study also found worse health outcomes in the hog counties than in the control—rates were higher for all-cause mortality, infant mortality, mortality from anemia, kidney disease, tuberculosis, as well as hospital admissions for low birth-weight infants. They also showed Group 2 rates for these conditions are significantly higher than national and state averages.

To control for overall racial health disparities in the US population, they identified zip codes in the control area that had similar racial, age, and income characteristics similar to those of Group 2, the most hog-intensive regions. Again, Group 2’s metrics generally came out worse than their hog-free peers. They also found a direct relationship between proximity and bad health outcomes—the closer you live to a big hog operation, the more likely you are to die or be hospitalized for kidney diseased, have a low-birth-weight baby, and suffer from other maladies.

Although the paper doesn’t establish that living near a factory-scale hog operation triggers these bad effects, it notes that doing so means being “chronically exposed to contaminants from land-applied wastes and their overland flows, leaking lagoons, and pit-buried carcasses, as well as airborne emissions” of toxic gases from manure lagoons. And it cites 11 papers, by a research team led by the late University of North Carolina professor Steve Wing, documenting ill health consequences from these exposures.

Now yet another hurricane is pushing toxic hog waste and carcasses into the community’s waterways, potentially intensifying the health threat to residents.

Meanwhile, the area’s residents are fighting back by suing the industry for destroying their quality of life. This past summer, juries sided with the plaintiffs in three separate lawsuits against Murphy Brown, the US hog-rearing arm of Chinese-owned pork giant Smithfield—and “there are twenty-three more lawsuits, and roughly 480 more plaintiffs” pending, reports the Triangle-based IndyWeek.

Between pissed-off neighbors and increasingly frequent mega-storms, the industry faces an uphill battle to maintain its hold over eastern North Carolina.