Mother Jones illustration; Getty

In late May, Coca-Cola announced it would produce 50,000 cans of New Coke as part of a promotional campaign linked to the third season of Netflix’s Stranger Things, which takes place in 1985, the same year the fizzy reboot made its short-lived debut. The new drink makes repeated cameos throughout the latest run, leading to a brief discussion of its qualities during an otherwise tense scene in episode 7.

“It’s delicious,” Lucas says, taking a long slurp. Five other kids stare at him in horror.

This is a fair representation of the prevailing literature on New Coke. For more than three decades, New Coke has been held up as the bad idea by which all other bad ideas are measured. Do a quick Google search for “the worst idea since New Coke” and you’ll find an encyclopedia of face-palms. Handmaid’s Tale–themed pinot noir. Mint-chocolate toothpaste. Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. No one seems to dispute its shortcomings, least of all the people who ushered New Coke into the world. On the 10th anniversary of the drink’s introduction, the company’s CEO, Roberto Goizueta, told employees, sounding more than a bit like Churchill after Dunkirk, that what happened was “a blunder and a disaster, and it will forever be.” People speak with less moral clarity about war crimes.

The popular version goes like this: In the early 1980s, not content with producing the world’s most recognizable beverage, greedy executives tweaked the recipe for the first time in 94 years. They redesigned the can, launched a massive marketing blitz, and promised a better taste. But Americans wouldn’t stand for it. In the face of a nationwide backlash, the company brought back the old formula—now dubbed “Coke Classic”—after two months. The story of New Coke is eternal. It’s a parable of hubris.

It’s also a lie.

Far from the dud it’s been made out to be, New Coke was actually delicious—or at least, most people who tried it thought so. Some of its harshest critics couldn’t even taste a difference. It was done in by a complicated web of interests, a mixture of cranks and opportunists—a sugar-starved mob of pitchfork-clutching Andy Rooneys, powered by the thrill of rebellion and an aggrieved sense of dispossession. At its most fundamental level, the backlash wasn’t about New Coke at all. It was a revolt against the idea of change. That story should sound familiar. We’re still living it.

There’s one big thing you have to understand about the New Coke rollout: If people actually liked Old Coke as much as they later claimed, the new version never would have existed. But in the early 1980s, the company’s fortunes were sagging. Soft drink sales were down across the board, but Coke was losing ground to the smoother, sweeter Pepsi. Coke was still doing well in places with a captive market, like restaurants or concessionaires, but at stores—where consumers had a choice—sales were dropping in a way that Pepsi’s weren’t.

Coca-Cola had been slow to adapt to changing preferences in the past. Diet Pepsi premiered in 1964, but it was another 18 years before Diet Coke debuted. In the meantime, the company offered sugar-free Tab, which carried a warning label informing drinkers that it was linked to bladder cancer in rats. Drink up! The journalist Bartow Elmore’s Citizen Coke speculates that the Reagan administration’s escalating drug war may have added a level of urgency to the company’s long-range planning by threatening Peruvian coca production.

So when researchers in Atlanta, in the process of belatedly developing Diet Coke in 1980, stumbled on a new formula, Goizueta and his fellow execs decided to study it. By late 1984, they’d decided to move ahead with a switch, and formed a small team to war-game the launch. They named their plan “Project Kansas” (an earlier iteration was dubbed “Tampa”) and drew inspiration from Dwight D. Eisenhower’s plans for the invasion of Normandy. That sounds made up but it’s not. The Project Kansas documents are displayed behind a glass case at the World of Coca-Cola museum in Atlanta. Here’s a sample:

In its size, scope and boldness, it is not unlike the Allied invasion of Europe in 1944. This is not just another product improvement, not just a repositioning or new product introduction. Kansas, quite simply, can not, must not fail.

As in the planning of a major military operation, it is necessary to understand the risks clearly, to plan contingencies, to build in the mobility to deal with those risks as they arise to confront the operation at various stages. In a meeting of the Core Strategy Group in Fort Lauderdale earlier this month, we took a look at the lessons to be learned from the 1944 Allied invasion, “Operation Overlord.”

The invasion led to a total Allied victory in less than a year. It was a broad strategic thrust that marshalled the ultimate resources of the allies to totally upset the strategic balance then existing. Its success changed the character of the war. If it had failed, the course of the war, if not its eventual outcome, would have been drastically altered.

It was a bold, decisive gamble; so bold and risky a roll of the dice that Winston Churchill persisted for two years in attempting to delay and divert the plan.

I mean, these are just insane things to say about a soft drink—Eisenhower, D-Day, things of that nature. But the point is, they didn’t just wake up one day and decide to change the formula. They obsessed over every detail, in mortal fear of failure, until everything was in order. In the document on display at World of Coca-Cola, someone has gone and underlined Churchill’s name by hand, as if to say, remember this, this is important, it will be on the test.

So why did they lose to the Germans?

At first, the mission showed promise. After months of secrecy—including fake leaks to throw reporters off—Coke announced its plans at Lincoln Center in New York City in late April 1985. The company had spent years testing the product, and the results to them seemed overwhelming. The new soda consistently beat out the old version across the country—even in Coca-Cola’s ancestral base, the South, where New Coke held a narrow 52-48 edge. When Southern testers were told the identities of the two samples, the popularity of New Coke jumped nine points. One bottler believed so strongly in the product that he threatened to sue the company if New Coke wasn’t released.

For the first few weeks, things were going well. New Coke won newspaper taste tests in Rochester, New York, and in Anniston, Alabama. Baseball fans in San Francisco liked it. Sales were up in Miami and Detroit. The London Observer’s panel of children preferred the new stuff to the old stuff, too. The company’s weekly telephone surveys of 900 consumers consistently indicated high favorability. Even people who preferred the old soda seemed okay with the switch. New Coke was good! At worst, New Coke was fine.

“Change,” a triumphant Coke executive declared, “is something the American people identify with.”

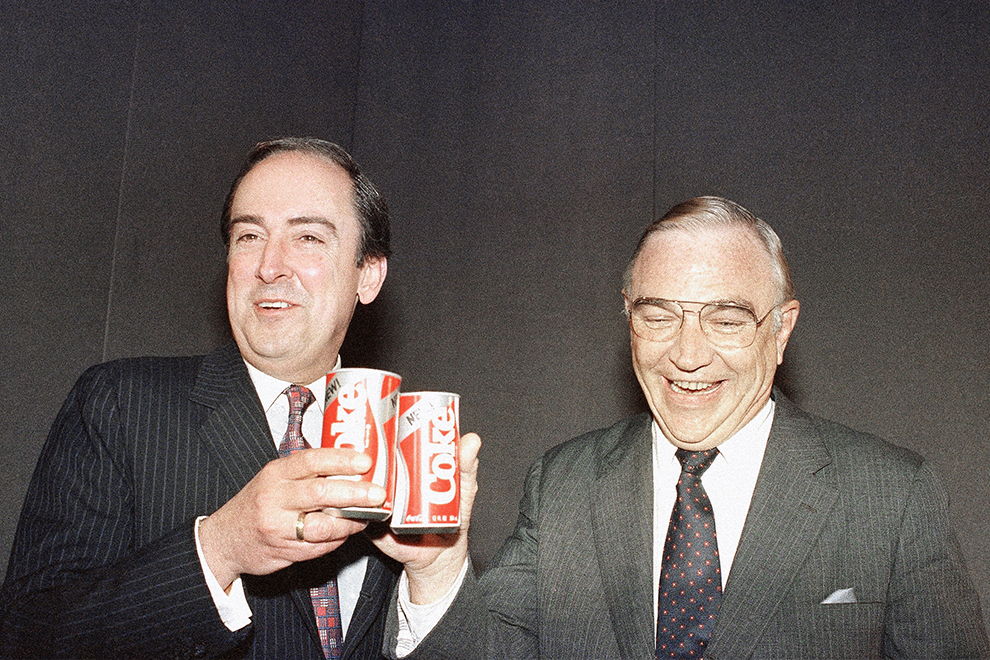

Marty Lederhandler/AP

A beverage’s broad popularity, though, is not a very interesting story. Dissent makes a good story. People expressing strongly held and borderline pathological opinions about soft drinks makes a good story. And it didn’t take long for reporters to start finding them.

In Wisconsin, the Wausau Daily Herald reported on the trials of a man named Andy Gribble. “So much of my life is changing outside of my control,” he told the paper. “Now Coke, the one thing left from my childhood, has been changed.” He was 19.

In San Antonio, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution (and the Chicago Tribune, and the New York Times) found a man named Dan Lauck who brought his own coolers full of soda with him to restaurants and drank five cases of old Coke a week—6.5-ounce glass bottles only, never cans. Lauck called New Coke’s debut “the blackest day of my life.”

“From now on my life will be divided into B.C. and A.C.—before the change in Coke and after the change,” he told the AJC. “I honestly don’t know what I’m going to do.”

In Seattle, a real estate speculator named Gay Mullins formed a group called Old Cola Drinkers of America and set up a hotline where people could call to voice their complaints.

“They have taken away my freedom of choice,” he told People. “It’s un-American!”

Former Coke CEO Neville Isdell writes in his memoir, Inside Coca-Cola, “You could feel the tension at headquarters, which was fielding similar complaints, even from bottlers who said they were ostracized at their hometown country clubs.” And since when has a country club discriminated against something for no good reason!

In some other context, these people would have been politely brushed aside, or at least some gentle soul might have introduced them to seltzer. But if, for a brief window in 1985, your sense of self was inextricably linked to soda consumption, if you were the kind of belligerent oddball who would tell someone at an airport, “You’ve ruined my life,” because his luggage bore the emblem of the soda company that had betrayed you—this actually happened to Isdell—newspapers treated you like the Oracle of Delphi.

It’s not hard to see in retrospect why people began to pile on. It’s fun to be cranky about stupid things. It’s almost the entire point of Twitter. But there was something else going on here. The critiques often weren’t really about soda at all.

Thomas Oliver’s 1986 book, The Real Coke, The Real Story, which is the definitive look at this saga, saw a strain of Southern reactionary politics in the backlash. “To them it was an extension of the Civil War,” he argues. “Here was Coca-Cola, a southern company, laying down its arms in deference to its Yankee counterpart.” Oliver means Pepsi, headquartered in Purchase, New York. He continues, “Coke, the quintessential southern drink, was changing its image and content to conform with the rivals in the North.”

That’s a little overwrought, but read the clippings and you realize he’s getting at something. “Changing Coca-Cola is an intrusion on tradition, and a lot of southerners won’t like it, regardless of how it tastes,” a University of Mississippi professor told the Chicago Tribune in 1985. “Why’d they announce it in New York?” wondered an Alabaman in the same story. It was another act of Northern aggression—a war between the tastes.

Early on in the saga, the Journal-Constitution conducted its own taste test at The Varsity, a venerable Atlanta drive-in, and reported that 45 of the 72 participants preferred the old stuff. Turns out people at the nostalgia factory love nostalgia! A quote from the restaurant’s co-owner sticks out because we’ve heard it before: “Why didn’t they test anybody here?”

These were the forgotten people, or so they wanted you to believe. They were sick of other people defining the pace and texture of change. In that respect, Coca-Cola was grappling with a monster of its own making, because it had spent tens of millions of dollars wrapping the corporation’s identity around this particular kind of small-c conservatism—an idyll of small towns and wholesome values, where all the women are strong, all the men are good looking, and all the kids have high blood sugar. In the early 1980s, it had rejected a proposal to make Michael Jackson a Coke pitchman, because, Oliver reported, he didn’t fit the company’s “All-American” image. He went to Pepsi instead.

You don’t have to listen to me speculate about what the New Coke backlash was really about, because the critics often came out and told you.

A New Jersey newspaper lamented that Coke was “catering to pantywaists” by abandoning its “macho” bite.

“Creeping yuppification, that’s what it is,” wrote syndicated columnist Mark Russell, echoing a common generational refrain. “Have a sweeter Coca-Cola with your green pasta, top it off with a frozen tofu cone, then put on a video and do your aerobics to a modem of synthesized quadri-sound.”

One Alabama newspaper columnist hinted at a foreign, possibly Communist influence behind the whole project:

I’ve had an uneasy feeling about Coca-Cola ever since a fellow by the name of Roberto Goizueta was named chairman and chief executive officer of the Coca-Cola Company of Atlanta, Ga., U.S. of A.

Roberto Goizueta, if memory serves me correctly, is from Havana, Cuba.

Imagine that…

At least some things hadn’t changed. Andy Rooney, the professionally cranky 60 Minutes personality, panned the new drink before he even tried it. “I’ve been very upset with the Coke people ever since they decided to phase out that great little green, hourglass-shaped bottle,” he wrote. Yeah, Andy, we know.

All wayward causes have their false prophets. The Stephen the Shepherd Boy of the New Coke backlash was Mullins, the Seattle retiree who told reporters he’d been preparing to move to Costa Rica before Coke forced him to stay at home and live out his Red Dawn fantasy.

“The Declaration of Independence and the Revolutionary War occurred because of taxation without representation; there was no freedom of choice,” he explained. “We went to war [in Europe] to help England, because another country was impinging on their freedom of choice. I feel that this is a battle of that magnitude.”

Bettmann/Getty

If you’re keeping score here, both camps have now compared their struggle to D-Day. But the statement is clarifying as to the nature of the fight. Mullins’ major gripe wasn’t about taste; it was about, as he put it, “the very fabric of America.”

Run out of a rented office in a downtown hotel, Old Cola Drinkers of America boasted of having 100,000 members. For $10, supporters could purchase “war kits” that included anti–New Coke bumper stickers. Mullins was a ubiquitous figure in the press, though estimates of how much of his own money he poured into the venture seemed to keep rising—it was $40,000, then it was $80,000, then it was $100,000.

Whatever the actual figure was, the Old Cola Drinkers were loud. They held protests, set up local chapters, and flooded Coca-Cola’s own hotline with complaints. Mullins and his followers filed a class action lawsuit to try to force Coke to abandon its new formula. It didn’t go anywhere, but that wasn’t really the point. The company had no good response to what Mullins’ guerrilla army was doing, and once Coke understood why, the war was over.

“We could have introduced the elixir of the gods” as New Coke, one executive said later, “and it wouldn’t have made any difference.”

Two months after New Coke launched, the company formally surrendered to Mullins. After announcing plans to bring back the old version, they added that they were sending the very first case to Mullins—this one guy in Seattle—via special delivery from Atlanta to a bottling facility in Washington State. The next day, newspapers across the country splashed Mullins on their front pages. He’s still wearing his anti-Coke T-shirt, baptized in the liquid from the bottles he’d stockpiled.

Americans, he said, had reclaimed “our heritage.”

Coca-Cola dubbed the product it reintroduced in July 1985 “Coke Classic,” but it wasn’t quite the recipe everyone at The Varsity was drinking in the ’40s. That version was made with cane sugar. Coke Classic—the new old Coke, or was it the old New Coke?—was made with high-fructose corn syrup instead. Eager to press the advantage won by Mullins and his pals, the sugar industry launched a new campaign arguing that the new old Coke was still not “the real thing.” And that was how America would come to learn something significant about the man whose rebellion, more than anything else, brought down a soda giant: He didn’t even like Coke.

After the dousing ceremony, Mullins hardly took a break. At the end of July, he held a press conference to announce his next crusade. He would not rest until Coke was once more made with real sugar. Coke Classic had made him sick, he reported. He felt ill after drinking only two rum-and-cokes.

A few days later, a group of sugar-industry reps from Hawaii, where the product was still made with sugar, invited reporters to watch them ship an eight-pack of old Coca-Cola to Mullins—bottles, of course—to encourage him to keep up his attack. “We wish you well in your crusade,” they said. “One man has made a difference.”

Within a few weeks—August 15—the Sugar Association, the Washington, DC–based lobbying shop for the beet- and cane-sugar industry, took out full-page ads in national newspapers echoing Mullins’ complaints:

The “Old Cola Drinks of America” is an organization that monitors consumer responses to soft drinks and other products. At a July 31 press conference, they turned their noses up at “Classic Coke” because it is sweetened with a cheaper sweetener—corn syrup—instead of sugar.

“It is not the original formula; it is not the Coke of my youth,” OCDA leader, Gay Mullins said at the time.

They were right. For 94 years Coca-Cola was in fact “The Real Thing”—a classic sweetened with real sugar—an unvarying taste standard known and trusted the world over. But five years ago, Coca-Cola quietly began to change its formula.

But wait a second. What was that last part? Coca-Cola had actually changed its formula five years earlier?

The real story slowly emerged. The Detroit Free Press put two and two together and asked Mullins why he had not previously mentioned, during his two-month campaign to bring back old Coke, that the stuff made him physically ill. Mullins said he thought at first the problem was with his own body, but he’d since come to understand that it was actually the beverage. He also blamed the switch for his inability to taste the difference between New Coke and regular Coke in a nationally televised taste test: Drinking Coke had killed his taste buds.

When Oliver, the author of The Real Coke, The Real Story, started digging around, the rest of Mullins’ story started to unravel. Old Cola Drinkers of America didn’t start off as a populist campaign. It was a hustle, plain and simple. Its founder hoped to sow conflict and cash in on it by getting either Coca-Cola or Pepsi to buy him out. It was an astroturf operation—or at least it would have been if either company had ponied up. After Coke Classic was reintroduced, Mullins even asked Coca-Cola to pay him $200,000 for an endorsement. (The company declined.)

His pivot to high-fructose agitation wasn’t exactly disinterested either. Mullins hoped that by joining the pile-on, he might entice the trade association to cut him in on some profits.

“We were interested in being supported by the Sugar Association,” he admitted to Oliver.

When the money he was hoping would come in from Big Sugar never materialized, he canceled a planned protest in Atlanta. The organization’s anti-Coke activism slowly faded. Membership in the group fell by 90 percent after New Coke was killed off, and the sugar-vs.-corn fight would be fought in the suites, not the streets. But Mullins made one last run of headlines before he and his group faded from view.

“Coke isn’t it anymore, not for Gay Mullins,” the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle reported.

“He’s hooked on Jolt Cola.”

There’s a whole body of research related to taste testing that later writers have used to try to explain away the New Coke fiasco. Malcolm Gladwell, who wrote about New Coke in his book Blink, points to studies showing that taste tests have a bias toward sweeter beverages. This helps explain why Pepsi (generally considered sweeter) based its whole ad campaign around taste tests, and why the New Coke tests led the company astray. People liked the first sip more, but maybe not the last hundred. This is a comforting explanation: It was actually a bad soda and here’s the science that proves it. By playing the first-sip game, Coca-Cola was essentially conceding the point to its opponent. As one Pepsi ad put it, “The other guy blinked.”

But many people really do prefer Pepsi, even after that all-important first taste. And the post-rollout company surveys of people who had finished their cans found a favorability for New Coke that matched the first-sip test. Maybe the sweet drink winning the sweet-drink contest doesn’t need too many caveats. Soft-drink trends have also proven Coke right about a willingness to adapt to new tastes: A majority of Coke sales today are non-Classic products, such as Diet and Coke Zero. Interestingly, people who have sampled New Coke in recent weeks, at places like BuzzFeed and Food & Wine, have given the beverage high marks because it reminds them of Diet Coke—it tasted weird then; it tastes like what’s normal now.

Coke executives, in their D-Day planning, always expected a small but vocal faction of Never-Cokers. What they miscalculated was the effect that those people would have on neutrals. Nine out of 10 Coke drinkers might have no problem with the change if you asked them individually. But put them in a room, and then put Andy Rooney in that room, and suddenly four of them are banging their fists on the table and talking about glass bottles. That’s how social influence works. It’s how containable brush fires become a blowup.

And Coke certainly didn’t count on the backlash linking up with larger currents of grievance in American life. Listen again to the words people used to describe how they felt—“heritage,” “freedom,” “tradition,” “American,” “Yuppies,” “tofu,” “New York,” “green pasta.” (Green pasta?)

This is how people talk when they’re channeling their resentment at something big into anger at something small. They invoke tradition when someone proposes a new taste, or when the tastes of some different audience or some new generation are appealed to. The dynamic is at the heart of basically every American culture war battle. The language can’t help but reveal its origins: a sense of dispossession on the part of people who possess plenty. Unhappy that the modern world no longer fully indexes itself to their preferences, they express their frustration in a way that only a largely unthreatened group would have the time for.

“Change is something the American people identify with,” the Coke executive boasted. But not everyone. Change was that nagging itch some people just couldn’t scratch. They were upset about the “Pepsi Generation,” not because of the Pepsi but because of the generation, and the changing of the guard it suggested. The nature of grievance politics is that no one else ever gets to drive.

We know this story. It’s familiar. This is country music rebelling against Elvis or Lil Nas X. It is people cutting the logos off their socks. It is Ted Cruz announcing Tuesday that he would boycott Nike for discontinuing a shoe he’d never bought. (There’s always a grift; it wouldn’t be true grievance politics without one.) It is protesting your alma mater because it replaced its racist mascot with a bear. It is every weird op-ed you’ve read about participation trophies or backpacks. It is the undercurrent of every cover story ever written about kids these days.

Frankly, I prefer the soda people to the rest of them. Not the Lost Causers, of course. I’m thinking of Mullins and his crew. There’s some value in bringing a corporate giant to heel, just to know we still can. Even if it was because a guy in Washington state wanted to make a quick buck. Maybe especially because a guy in Washington state wanted to make a quick buck. You can’t let the suits get too comfortable. Every now and then they have to see the flames in the whites of your eyes.

But anyway, it’s all a little late to be having this conversation. After all, soda’s dead now. Didn’t you hear? Millennials killed it.