Kim Morris, head cook at Bella Vista School in Bella Vista, Ca, watches as students utilize the salad bar. Andreas Fuhrmann/The Record Searchlight/Associate Press

A few weeks ago, I went back to school—literally, to the elementary school of my 1970s childhood in Austin, Texas. But I wasn’t (just) on a Proustian journey to recover the past. Instead, I went in search of something equally elusive: a free lunch. I had heard that Austin Independent School District’s Anneliese Tanner, the executive director of food services, was using administrative magic to serve high-quality, made-from-scratch meals to the district’s 80,000 kids, half of whom come from economically disadvantaged families. The kicker: At 82 of the district’s 129 schools—including my alma mater, Pecan Springs—the lunches are free for all children.

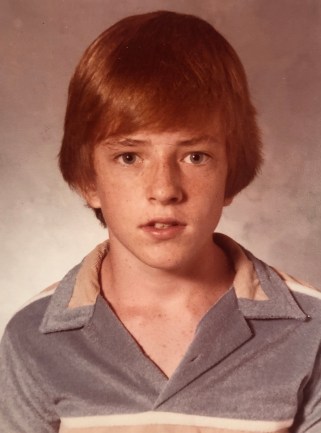

Take a trip to Pecan Springs, the elementary school Tom attended in the late 1970s, on the latest episode of Bite podcast:

Pecan Springs Elementary School annual photo, late 1970s.

When I arrived at the door of the midcentury brick building on a sunny Tuesday morning in early September, I was surprised to feel butterflies in my stomach—a throwback to my early-childhood terror of institutional settings that made the beginning of first grade a struggle. Then I had to check in at the principal’s office—where I was chastised in the fifth grade for participating in a conflict with the private school next door. More butterflies! All of that dissipated upon walking into the cafeteria. There, I was overcome, not with melancholic ruminations on my long-lost childhood, but rather by the joy and chaos of adorable first graders chowing down.

In a relatively quiet corner of the lunch room, I sat down with Tanner to try out the day’s fare: a toasty whole-wheat burrito featuring a mix of pureed beans and melted cheese; and a salad featuring crisp romaine, cherry tomatoes, black beans, corn, ground beef, and guacamole. The food was satisfying and fresh—nothing like the reheated square pizza chunks or pre-fab Salisbury steak I once wolfed down as fast as I could, so I could be excused to go roughhouse in the yard.

These days and in my childhood, the federal school lunch program confronts kids with a three-tiered price model based on family income level. Kids in households with incomes at or below 130 percent of the federal poverty line ($25,100 a year for a family of four) pay nothing; those in households with incomes between 130 and 185 percent of poverty pay $0.40; and all others pay $3.00. Not only does this form of lunch-room economic sorting risk embarrassing kids from low-income families; it also leads to mortifying cases of “lunch shaming,” where kids with past-due cafeteria bills can be stigmatized by being served off-menu cold cheese sandwiches and other punishments.

At Pecan Springs these days, all kids eat free—as is the case with about two-thirds of AISD schools, Tanner explained. Despite its status as a fast-growing, tech-centered city, Austin has pockets of hidden poverty, reflected in the high poverty rate of the student body. Using a little-discussed provision of the 2010 Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act—the school lunch reform law championed by then-First Lady Michelle Obama—Tanner made free lunch a reality for everyone in 82 of Austin’s 129 schools.

Under the provision, when at least 40 percent of students in a school qualify for free lunches, the school can claim “community eligibility”—meaning all students automatically have access to free lunches. The program eases the administrative burden for high-poverty districts, allowing them to shift resources from paperwork to better meals, Tanner said. She added that the community eligibility provision has been crucial to her push to ensure that every Austin school kid has access to a scratch-made healthy lunch.

Resources are tight—under federal reimbursement rates, Tanner has a little more than a dollar to spend on ingredients per meal. But in her schools with universal free lunch, she added, more kids queue up in the cafeteria and fewer kids opt to bring in bagged lunches. And higher participation rates mean more federal dollars and thus more buying power for high-quality ingredients.

The community eligibility provision is shaping up to be an underground path to providing universal free lunch for US school children, freeing them from the class humiliations of the three-tiered price model. Jennifer Gaddis, author of the soon-to-be-released The Labor of Lunch: Why We Need Real Food and Real Jobs in American Public Schools, argues that universally free, from-scratch lunches turns the school cafeteria into a vital community resource: one that helps kids develop healthy eating habits and provides skilled jobs for workers.

Meanwhile, Republicans are trying to deflate the community eligibility program. Back in 2016, a bill in the then-GOP controlled House of Representatives would have raised the poverty threshold from 40 percent of a school’s students to 60 percent, which would have forced 7,000 schools with nearly 3.4 million students to potentially fall out of the program.

That failed, but new Trump administration machinations could still damage the program. In July, the US Department of Agriculture proposed new rules that would knock 3 million people—including 500,000 kids—off the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Kids whose families qualify for SNAP automatically qualify for free lunch, and count toward the 40 percent minimum needed for schools to qualify for universal free lunch. The administration is expected to release final rules in the coming weeks.

Pecan Springs, which has an economically disadvantaged rate of 94 percent, won’t likely see its free-lunch program imperiled if a few kids get booted from SNAP. But schools with rates near the 40 percent mark could, Crystal FitzSimons, director of school programs at the Food Research and Action Center, told me. She says it’s too early to tell how many schools, and how many kids, could be affected.

After sitting at my old school eating a flavorful, healthy lunch among first-graders, I’m convinced lunch should be free—from both price and stigma—for all kids.