Tiago Galo

The labs of Evolve BioSystems are full of baby poop. Tucked into a shopping mall in Davis, California, alongside a Jazzercise and a marijuana dispensary, this biotech company has gathered infants’ feces from all over the country. “Millions of people every day are throwing away poopy diapers, and they don’t realize how much information is actually contained in each poop,” says Robin Flannery, Evolve’s director of clinical development and operations. “It tells us a lot about what’s going on inside the baby.”

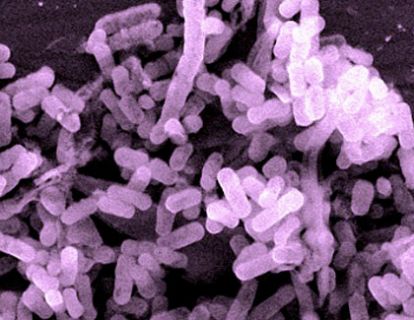

Specifically, Evolve is interested in one potentially very powerful type of bacteria found in babies’ intestines: B. infantis. Its researchers, including several scientists at University of California, Davis, think the bacterium flourished in babies’ bellies for thousands of years. But today, the company’s research shows, in about 9 out of 10 American babies, B. infantis has disappeared. Without it, they say, kids are missing out on a host of health benefits.

Take the case of Jack Graw, a newborn who underwent two rounds of high-dose antibiotics during treatment for a collapsed lung in 2017. The drugs prevented infection but also likely wiped out beneficial bacteria in his gut. Once he went home, Jack screamed during feeding and developed a “horrible rash” on his butt, his mom, Katelyn Graw, told me. Within a week of giving Evolve’s B. infantis probiotic a try, his symptoms practically vanished.

Fussiness, diarrhea, and rashes aren’t necessarily life-threatening, of course. But Evolve’s researchers say the symptoms are caused by the same bad bacteria linked to a whole host of conditions, from asthma and allergies in children to diabetes and obesity later in life. And independent research focusing on the microbiome—the collection of microorganisms that live in our bodies—has linked the health of our bowels’ bacteria to all sorts of ailments, including acne, depression, and cancer, suggesting Evolve might be on to something.

Here’s how it works: When B. infantis breaks down carbohydrates from breast milk into acids, the baby’s gut becomes more acidic, which in turn defends them from dangerous bacteria like clostridia, E. coli, staph, and strep. One study by Evolve’s researchers found that B. infantis reduced potentially harmful gut bacteria by 80 percent. Other studies suggest that B. infantis may help strengthen a protective layer in the colon and reduce intestinal inflammation.

The company has a lot to gain by proving their hypothesis. Evolve’s Evivo probiotic, a powder that parents can mix into breast milk or formula and feed to newborns through a syringe, hit the market in 2017 and has since made its way to thousands of babies. A one-month supply goes for $80 on Amazon. The company has also received millions in funding from the Gates Foundation and other philanthropic organizations that see Evivo as having huge potential in developing countries.

With Evivo, the company is wading into a multibillion-dollar marketplace of probiotic supplements aimed at keeping the microbiome healthy. But the industry is poorly regulated and full of bogus treatments, which makes it difficult for consumers to distinguish science from snake oil. Despite the research backing up its product—last year, Evolve published its eighth peer-reviewed study—the company still has to convince skeptics. A few of the independent experts I consulted expressed concern that the company may be getting ahead of the science. Praveen Goday, a pediatric gastroenterologist at the Medical College of Wisconsin, notes that microbiome science is still in its infancy. “I’m not sure we know enough to be able to characterize all [bacteria] as just ‘good’ and ‘bad,’” he says. (Evolve advertises B. infantis as a “good” bacterial strain.)

One big mystery: While B. infantis is absent in most American infants, research shows babies in developing countries like Venezuela, Bangladesh, and Gambia are “dramatically colonized” with it—and see lower rates of diseases like Type 1 diabetes and food allergies (though no link has been established between the two trends). Evolve’s researchers suspect something has nearly wiped out this bacterium in industrialized countries—perhaps overuse of antibiotics and cesarean sections, which prevent the transfer of bacteria to babies, as well as the use of infant formula over breast milk. B. infantis is typically passed from mother to child, so if moms don’t have it in their guts, their babies won’t either.

Right now, the company is focused on producing the research to answer these questions. And that means cutting through the crap science with, well, crap. As Evolve’s Flannery says, “I think a lot of people say, ‘Oh, well, my baby doesn’t need a probiotic because they’re healthy,’ but I would say, ‘Let’s take a look at your baby’s poop and then we’ll decide how healthy they are on the inside.’”