Getty Images

Weeks before most of us sensed the depth of the pandemic crisis, the country’s servers, chefs, and bartenders were staring it down. Their industry relies on people coming together, in public spaces, and in close quarters. It figures that the majority of the 33 million Americans who have filed for unemployment during the viral pandemic worked in restaurants.

Celebrity chefs were early in sounding the alarm about the crisis and quickly jumped into action. David Chang, chef and owner of the Momofuku empire, warned reporters back in March that the pandemic could destroy the restaurant industry for good. Chef and Top Chef judge Tom Colicchio marshalled together the Independent Restaurant Coalition, a lobbying operation as professional as any on Capitol Hill, to advocate on behalf of chef owner-operators. After Congress passed its first emergency relief package in late March—and the small business loans immediately ran dry—IRC members demanded a $100 billion restaurant stabilization fund uniquely tailored to their industry. Without serious government intervention, Colicchio imagines that half of restaurants will close for good.

Hear Tom Colicchio and Tunde Wey on the latest episode of Bite:

Restaurants require a special kind of bailout, IRC members argue, because their industry felt the effects of the crisis first, and will continue to feel them long after many other trades return to normalcy. And restaurants will be required to restore stability. “Once we’re through this, where are we going to go to feel normal again?” Colicchio told my colleague, Tom Philpott. “You want to go to your neighborhood restaurant, you want to sit at the bar where you would go on a Thursday night and have a cocktail. You want to go have the dish you crave.” To forgo saving the nation’s eateries, he seems to argue, is to abandon a crucial cornerstone of America.

But even as high-profile restaurateurs make the case for a special bailout, other industry veterans are wondering: Is the pre-pandemic restaurant industry really something we want to return to?

Before the crisis, plenty of restaurants teetered on unaffordable rents, preposterous ingredients, underpaid labor, and razor thin margins. So when he spotted calls for the government to bail out the restaurant industry, Nigerian-born, New Orleans-based chef and activist Tunde Wey suggested, in a series of Instagram posts, that the government should instead “let it die.”

“We want to keep our restaurants open so that we can employ people. But then you examine and you think about it, what sort of employment are you advocating for?” Wey asks. “The sort that we had before? Well, that’s terrible.”

The cracks in the industry’s foundation started to show in the aftermath of the last recession, says Kevin Alexander, a food journalist and author of the recent book, Burn the Ice: The American Culinary Revolution and Its End. When the economy crashed in 2008, chefs struggled to get the financial backing required to open brick and mortar eateries. Instead, they opened gourmet food trucks, counter-service shops with mismatched plates and furniture, and pop-ups in whatever vacant spaces they could find—new models that all emphasized the quality of meals above overhead. Le Pigeon, for instance, opened in Portland, Oregon, in 2006 by chef Gabriel Rucker, privileged a made-from-scratch menu with dishes such as grilled squab and couscous studded with pigeon hearts.

As this style of restaurant took off, the trends made their way to neighborhood joints with more modest ambitions. More than 100,000 new restaurants opened their doors in the 2010s, many of them in cities that affluent Americans began flocking back to after a half-century in suburbia—places like Austin and Nashville. But as they did, a decade of uninterrupted economic growth led to rising rents, increased labor costs, and heightened competition. “The only people making money were the folks with their own restaurant groups, who’d gotten very good at recognizing opportunities, moving quickly to take advantage of them, and elbowing out all competitors,” Alexander says.

Gabrielle Hamilton, the chef and owner of New York fine dining beacon Prune, noted that these rising costs have been hard on the bottom lines of even the most successful restaurants, like hers. “I’ve joked for years that I’m in the nonprofit sector, but that’s been more direly true for several years now,” she wrote in the New York Times last month, referring to how her revenue has flat-lined as her expenses exploded.

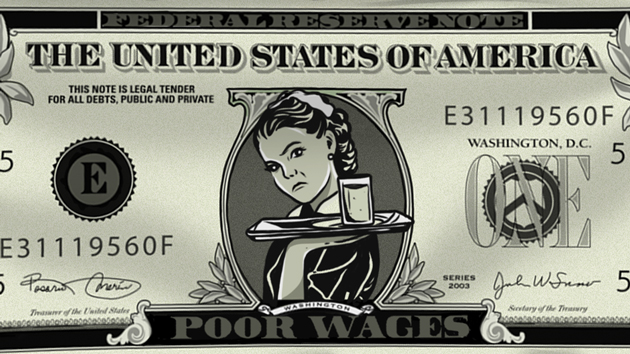

These boom years also saw an attendant spike in income inequality, a hardship that restaurant workers unduly bore: Dishwashing, food preparation, and hosting jobs consistently rank among the worst paid positions in America. That disparity was even more acute for restaurant workers of color: A 2019 analysis from Restaurant Opportunities Centers (ROC) found that fewer than 18 percent of California’s restaurant employees of color—who make up 70 percent of the industry—made $31 or more per hour, while 35 percent of white employees did.

Wey witnessed these inequities first-hand in New Orleans, where he’s lived for the last several years. When he first arrived, he operated a stall in St. Roch’s Market, a food hall restored in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. (At that stall, Wey drew attention for charging his white customers more than what his black customer paid.)

St. Roch’s had been restored with FEMA and state grants that seemed to kick-start a triumphant rebound of New Orleans’ restaurant industry. But Wey argues that the success primarily benefit white restaurant owners—not the workers or the 60 percent of New Orleans residents who are Black. Wey points to research that shows 40 percent of the city’s businesses are black-owned, but account for just two percent of all receipts. “Working class folks, immigrant folks have to work 50, 60, 70 hours a week just to be able to pay rent, buy food, and not have healthcare,” Wey says. “Where’s the nobility in that?”

The coronavirus shined a light on a broken system. And calls for relief exposed some uncomfortable truths. The emergency relief package Congress passed in March set aside forgivable loans for small businesses to keep workers on payrolls. Colicchio and other IRC members argue that restaurants can’t really make use of these loans: Under the Paycheck Protection Program rules, a loan—which covers two months’ worth of payroll, rent, and utilities—is forgivable only if an employer can hire back three-quarters of its staff during that time.

But restaurant workers in many states rely on tips for much of their salary. Without the tips, these workers make as little as $2.13 an hour in wages—the legal rate in 16 states and territories, including Texas, North Carolina, and Indiana. So why would furloughed restaurant staff return to a less-than-minimum wage paying job with no tip money to supplement it? “It’s a romantic idea to us—working with our hands and feeding people and doing all of those things,” Wey says, “but what holds that up is a fundamentally unequal system.”

Instead of bailing out the way the restaurant industry was, Wey calls instead for restaurant owners and workers to join together to call for a “fundamental retooling of the economy.” On his agenda: a slate of progressive reforms popular among supporters of Bernie Sanders, including a federal job guarantee, Medicare for all, and a public works program under a Green New Deal. “The other thing is we address the historical, and also contemporary injustice that persists,” Wey says, calling out the need for reparations for the descendants of African-American slaves.

Alexander says that he doesn’t realistically see a reward structure in our current economy that would incentivize all of those sweeping changes. But he does think this financial crisis, just like the last one, will offer a tremendous opportunity to reimagine the restaurant industry. He predicts that the next “culinary revolution” will be in the hands of patrons who might now refocus their dollars and attention on their neighborhood spots over the far-flung destinations they once sought out based on Yelp reviews. He could even imagine new neighborhood eateries being owned cooperatively, an evolution of the GoFundMe campaigns that have sprung up to save restaurants, as a recognition of their importance to a community.

“In the same way that you recognize the health workers and what they’re doing, we’re recognizing the people working in the food industry and feeding you during this time,” Alexander says. “Hopefully, you’re much more appreciative of the way that works.”

Tom Philpott contributed reporting.