In the decades before the Civil War, one of the South’s largest slave enterprises held sway on the northern outskirts of Durham, North Carolina. At its peak, about 900 enslaved people were compelled to grow tobacco, corn, and other crops on the Stagville Plantation, 30,000 acres of rolling piedmont that had been taken from the Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation. Today, the area has a transitional feel: Old farmhouses, open fields, and pine forests cede ground to subdivisions, as one of America’s hottest real estate markets sprawls outward.

For more articles read aloud: download the Audm iPhone app.

On a sunny winter afternoon, farmer and food-justice activist Tahz Walker greets me on a 48-acre patch of former Stagville property called the Earthseed Land Collective. Walker and a few friends pooled their resources and bought this parcel, he says, to experiment with collective living, and inspire “people of color to reimagine their relationship to land.” He leads me through the gate of the property’s Tierra Negra Farm, a 2-acre plot of vegetable rows, hoop houses, and a grassy patch teeming with busy hens. It’s one of several enterprises housed within the land collective, which also features a commercial worm-compost operation, a capoeira studio, and homes for several members, including the 1930s farmhouse where Walker lives with his wife and co-farmer, Cristina Rivera-Chapman, and their two kids. Tierra Negra markets its produce through a subscription veggie-box service that goes to 20 nearby families—including descendants of Stagville’s enslaved population—and supplies Communities in Partnership, a local nonprofit that brings affordable fresh food to historically Black, fast-gentrifying East Durham.

As it’s January, most of the rows are fallow. Walker points to a patch of bare ground that grew sweet potatoes the previous season. “It’s a variety that was grown by a Black farmer in Virginia for like 40 years,” he says. “He stopped growing them, and I started growing them from slips,” referring to the green shoots used to propagate sweet potatoes. “It’s a cool variety—instead of running, it kind of bushes up, so it’s really great for cultivation with the tractor.” And “it still makes great pies and fries.”

Like many Black Americans born in the second half of the 20th century, Walker has ancestral ties to agriculture, but he grew up alienated from it. His father had spent summers working on his family’s farm operation in rural Kentucky, where they sharecropped on land owned by white people. Walker’s dad fled as soon as he could and ultimately set up an IT-services business in Atlanta, raising Walker and his sister in the city’s then-semirural far northern suburbs. Stories about life in the Kentucky fields were scarce. To his father, farming represented “trauma [that] gets passed down,” something to escape. When Walker began to devote his life to agriculture as a young adult in the late 1990s, “my dad would always say, ‘Everybody’s trying to get off the farm. Why are you trying to get on the farm?’”

Tahz Walker holds a tray of kale at Tierra Negra Farm.

Madeline Gray

Walker is part of a growing movement of young Black Americans striving to reclaim the legacy of agrarianism. Acquiring land isn’t easy, as he knows all too well: A century of land loss has been compounded by escalating real estate prices. Yet the quest to reclaim farmland is gaining momentum as part of the broader reparations movement, which seeks redress for the unpaid debts owed to many Black Americans.

After a traumatic history marked by enslavement and then sharecropping, followed by a century of racist federal farm policy that largely stripped Black farmers of the ability to hold land, “I never in my wildest dreams thought that there would be young people wanting to become farmers,” says Karen Washington, a pioneering community gardener in the Bronx who now co-owns a farm in the Hudson Valley. While the wounds of the Black agricultural experience can’t be forgotten, Washington says, “a different narrative has started to surface: power behind owning land and controlling what you eat.”

In January 1865, Maj. General William Tecumseh Sherman met with a group of Black ministers in Savannah, Georgia, to discuss the path forward for 3.9 million recently freed Black people. “The way we can best take care of ourselves is to have land and turn it and till it by our own labor,” a Baptist minister and former slave named Garrison Frazier told Sherman. The general proposed to expropriate 400,000 acres owned by white plantation owners and grant it to freed slaves in allotments not to exceed 40 acres. The region would be politically autonomous, with the “sole and exclusive management of affairs…left to the freed people themselves.” Sherman’s Special Field Orders, No. 15, popularly known as “40 acres and a mule,” were soon approved by President Abraham Lincoln, but died with him; his successor, the Southern white supremacist Andrew Johnson, hastily canceled the orders.

As the land remained in the hands of white plantation owners, millions of Black people had little choice but to work as sharecroppers—tenants who rented a patch of farmland in exchange for an often-meager share of the harvest. This arrangement quickly morphed into a form of debt peonage. Sharecroppers had to rely on high-interest loans from their landlords and merchants to run their operations, leaving scant profit. The ruling white gentry, in turn, used credit as a tool to ramp up production, which “forced sharecroppers to grow ever more cotton, the only crop that could always be made into money,” Harvard historian Sven Beckert writes in his book Empire of Cotton: A Global History. As cotton output rose, prices fell, putting sharecroppers on a debt treadmill, enabling the Southern ruling class to continue extracting monumental wealth from the labor of Black people long after abolition.

And yet, despite violent backlash from Southern planters, Black growers managed to gain a toehold. The key was collective action, University of Wisconsin sociologist Monica White explains in her book Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement, 1880–2010. Launched in 1886 to organize landless Black farmers and to pool money to buy land and tools, the Colored Farmers’ National Alliance and Cooperative Union boasted 1.2 million members at its peak. At the Tuskegee Institute, the Alabama land-grant college founded by Booker T. Washington and other formerly enslaved people, agricultural scientist George Washington Carver pushed crop diversification, composting, and other proto-organic methods to help sharecroppers “make enough profit to purchase their land, feed their families, and achieve economic autonomy,” White writes. Carver toured Alabama in an “agricultural wagon,” delivering lectures and demonstrations of his techniques.

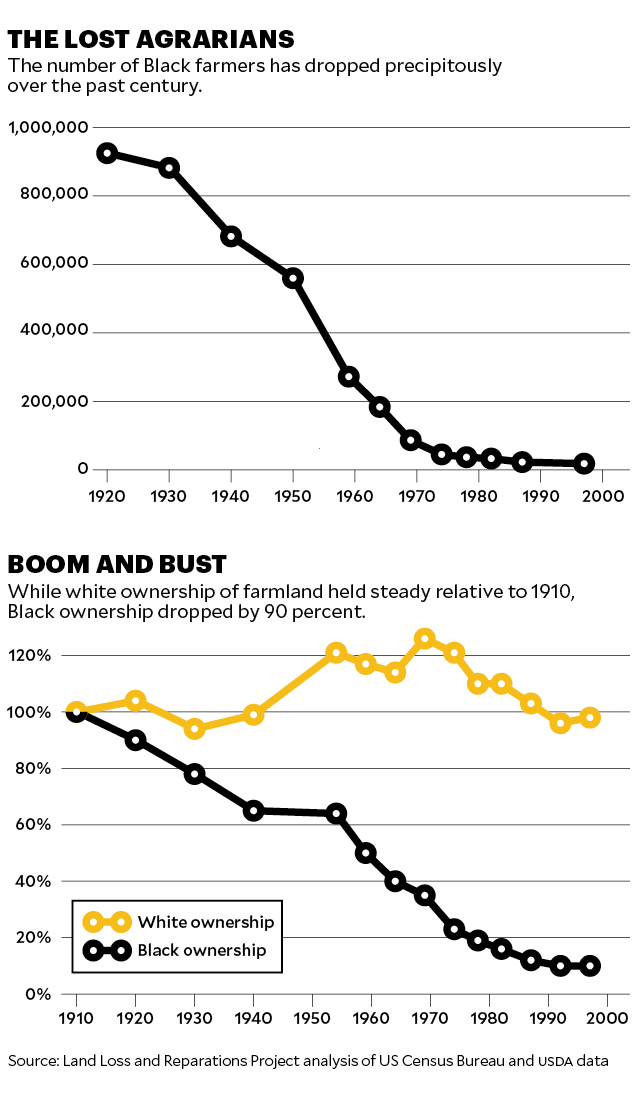

These efforts helped Black farmers acquire land against long odds at a time when ownership was the surest path to a measure of economic security within a highly stratified, racist society. By 1910, although sharecropping remained dominant, the US census reported, about 219,000 Black farmers owned land. Together, the Land Loss and Reparations Project found, they held an estimated 20 million acres. According to Thomas Mitchell, co-director of Texas A&M’s Real Estate and Community Development Law program and an expert on Black land tenure, as many as 80 percent of the Black middle or upper-middle class at that time were farm owners.

Those Black landowners would soon come under severe attack. As historian Pete Daniel shows in his 2013 book, Dispossession: Discrimination Against African American Farmers in the Age of Civil Rights, the loss of Black farmland accelerated after the Great Depression, driven by two factors. One was the industrial revolution that had transformed farming: Farmers had to scramble to pay for expensive new fertilizers and machines, while the resulting boom in crop yields triggered a steady fall in prices. The total number of farms plunged from 6.8 million in 1935 to fewer than 3 million in 1974. The Department of Agriculture, Daniel shows, promoted the modernization push, plying rural areas with loans and aid to encourage the adoption of new technologies. While millions of farms failed even with a gusher of post–World War II USDA support, few could survive without it.

But all that government support flowed through the far-flung county offices of various Department of Agriculture agencies, which were often dominated by local white landholders. As the revolt against Jim Crow gained force, “USDA programs were sharpened into weapons to punish civil rights activity,” Daniel notes. Black farmers found themselves increasingly cut off from the aid they needed to survive, resulting in defaults, bankruptcies, and forced sales on a grand scale. To make matters worse, “planters evicted tenants and sharecroppers who attempted to register to vote and replaced them with machines and chemicals,” Daniel writes. Poverty and hunger within rural communities spiked, driving the Great Migration of Black people fleeing the agrarian South for factory jobs in the urban North and West, which in turn reinforced white political power back home.

Some Black farmers who stayed responded once again by forming cooperatives. Fannie Lou Hamer, born in 1917, grew up picking cotton on her family’s sharecropping operation in Mississippi. After being evicted from the plantation for her voting rights activism in 1962, Hamer quickly seized on land tenure as key to Black liberation. In 1969, she launched the Freedom Farm Cooperative in Sunflower County, Mississippi, one of the poorest, most agriculture-intensive regions in the country, using what we would now call crowdfunding, cobbling together fees from speaking tours with donations from a nationwide campaign led by Harry Belafonte. At its peak in 1972, the Freedom Farm Cooperative housed 70 families who grew commodity crops like cotton and wheat as well as fresh vegetables that fed another 1,600 families in the surrounding community.

Fannie Lou Hamer, who launched the Freedom Farm Cooperative in 1969, was outspoken about land tenure as key to Black liberation.

AP

Then a series of floods and droughts struck, and Hamer became seriously ill. In 1976, the Freedom Farm Cooperative had to sell its land to pay back taxes. “The dream of a self-sufficient agrarian community was over,” recounts White. Yet today Hamer’s model is inspiring the next generation of Black agrarians to create “an oasis of self-reliance and self-determination in a landscape of oppression maintained in part by deprivation,” White adds.

White farmers, too, felt the brunt of the postwar rise of industrial agriculture, which drove millions of them out of business. But when they sold out, their land was largely bought by other white people, meaning overall white land ownership held steady. Lost Black farmland, however, also largely accrued to white people. The result is that the number of Black farmers has dropped by 98 percent from its high in 1920, and the total amount of Black-owned farmland has withered to 10 percent of its peak.

This change amounted to an enormous transfer of wealth from Black to white people. When a family is forced to sell off its land at fire-sale prices, the loss cascades through generations. Land was wealth—an asset that could be used to borrow money. “You could use the land as collateral to get a loan to send your kids to college or university and improve their economic outcomes,” Mitchell says. Along with Harvard scholar Nathan Rosenberg and journalist Bryce Stucki (who, with Kathryn Joyce, co-wrote an investigation accompanying this article), Mitchell is part of a research team called the Land Loss and Reparations Project, which is analyzing the economic impact of the great dispossession. According to its preliminary analysis, the total economic hit to Black wealth from land loss could be in excess of $300 billion—a significant contributor to the persistent racial wealth gap that hangs over US society. Today the median white family is nearly 10 times wealthier than its Black counterpart.

The consequences continue to reverberate. George Floyd, whose murder last year by now-convicted Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin sparked global protests, grew up in a public-housing project in a “predominantly Black Houston neighborhood where white flight, underinvestment and mass incarceration fostered a crucible of inequality,” reported the Washington Post’s Toluse Olorunnipa and Griff Witte. One reason Floyd’s family lacked resources: His great-great-grandfather, Hillery Thomas Stewart Sr., had 500 acres of North Carolina farmland stolen from him in the late 19th century, the Post reports. Instead of inheriting property that would have ballooned in value over the 20th century, his children worked as sharecroppers.

Agriculture, the backbone of the Black middle class just a century ago, has largely vanished as a force in Black American life. According to the latest US Census of Agriculture, only 1.7 percent of farms were run by Black people in 2017. Meanwhile, the value of farm real estate has exploded: During the 20th century, its price rose dramatically, and has continued its ascent since, representing both a devastating loss of Black wealth and a major obstacle for would-be farmers trying to break into agriculture.

Despite these odds, there are signs of a resurgence of interest in farming among young Black people. In Virginia’s Northern Neck region near Chesapeake Bay, Chris Newman, the son of a Black mother and a Native American father, left a tech career in 2013 to launch Sylvanaqua Farms, where he raises chickens, cattle, and hogs on pasture along with vegetables. From his Instagram and Medium accounts, Newman has emerged as one of the most influential voices in the movement, laying out a vision of agriculture quite different from the Jeffersonian family-farmer model that, he argues, thrived on stolen land and labor and now functions as a bulwark for maintaining white dominance.

Then there’s Leah Penniman, who uses her farm in upstate New York as a training ground for farmers of color, and whose book Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land is, she writes, a “reverently compiled manual for African-heritage people to reclaim our rightful place of dignified agency in the food system.” From 80 acres of land surrounded by forest, Soul Fire markets its fruit, vegetables, meat, and eggs through a sliding-scale subscription vegetable-box service using the principle of ujamaa, a form of cooperative economics developed in Tanzania. The group’s impact goes well beyond its efforts to deliver fresh food to low-income neighborhoods in Albany, near where Penniman once worked as a public school teacher. Its weeklong immersion courses have provided more than 100 aspiring growers of Black, Indigenous, and Latino heritage on-the-ground training to “heal from inherited trauma rooted in oppression on land, and take steps toward [their] personal food sovereignty,” as the group’s website states.

As children in the 1980s, Penniman and her siblings split time between rural Massachusetts, where they lived most of the year with their father in a trailer, and Boston, where they spent summers with their mother. Out in the country, she and her sister would “go out into the woods and propitiate the trees and the soil and the rocks and bring offerings,” she recalls. “When we were very little, maybe were 6, 7 years old, we thought we invented this new religion called Mother Nature.”

Ironically, it was in the city where she experienced an agrarian awakening. In 1996, at the age of 16, she got a summer job at the Food Project, a Boston-based program that taught teenagers to grow food for soup kitchens at a community garden and a 40-acre farm in the suburbs. “I just fell in love with that elegant simplicity of seed-to-harvest,” she says. “It was just undeniably good.”

The experience led her to seriously consider a career in farming: “I went to all the conferences, I read all the books.” But in college, she almost gave up on agriculture: “I was disillusioned by the fact that everybody was white at these conferences.”

At the 2010 Northeast Organic Farming Association conference in Amherst, Massachusetts, Penniman had a fateful encounter with Karen Washington, the community-garden activist. “She said to me, ‘Don’t give up, one day we will have our books, we’ll have our conferences, we’ll have our community, because this is our heritage.’”

Not long after, Washington launched the inaugural Black Farmers & Urban Gardeners (BUGS) conference in Brooklyn. The annual conference has emerged as a space where Black agrarians of many kinds—young, old, city, country, Southern, Northern—meet, compare notes, and collaborate on a future that centers food and land justice. Penniman says the urban-rural connections highlighted by BUGS are a driving force of the new Black agrarian movement. “Almost everybody who comes to our trainings at Soul Fire and is interested in commercial farming or larger-scale farming started out in these [urban] community gardens, like the Garden of Happiness in the Bronx that Mama Karen started,” she says. “The folks who’ve held on to that little bit of earth, that little corner of soil are the folks who are going to be feeding us in the future.”

And collaboration remains key. Working with a network of new and aspiring farmers, Penniman helped launch the Northeast Farmers of Color Land Trust in 2019. The trust came about through the realization among young farmers of color that land in the region is “really hard to access, it’s expensive, it gets scooped up by wealthy investors,” says Stephanie Morningstar, the group’s director and a member of the Mohawk Nation. The group hopes to acquire at least 2,000 acres of farmland over the next five years, and to make it available to Black, Indigenous, and Latino farmers through long-term leases.

The May 2020 murder of George Floyd and the subsequent wave of Black Lives Matter protests “just broke open a dam,” leading to “tons” of offers to donate parcels of land to the trust, she says. At the same time, the trust is taking it slow, acknowledging that the region is essentially the “unceded territory” of “dozens of sovereign nations” with whom it must build relations before it can accept and manage the land in good conscience. Currently, Morningstar says, “we’re a land trust without land, because we’re building trust.”

For most young Black farmers, land is out of reach. To launch their operation, Walker and Rivera-Chapman did what a lot of aspiring farmers do: They rented. Their vision was to grow top-quality food for underserved communities within the Raleigh–Durham–Chapel Hill “Triangle,” a region marked by rapid economic growth and massive racial and economic inequality. Open land within easy range of the Triangle is pricey. So for several years, Tierra Negra was an itinerant operation, hopping from rented patch to rented patch held by owners always on the lookout for more lucrative tenants.

The hoop house on Tierra Negra Farm

Madeline Gray

But that approach was in direct opposition to the organic agriculture Walker and Rivera-Chapman are devoted to. Growing food that doesn’t rely on chemical pesticides and fertilizers requires years of patient investment in the soil. “The last straw” came in 2017, when the couple rented an acre-and-a-half plot in downtown Durham. The price was reasonable—around $500 per month—but the landlord, a New York investor, could void the lease at any time with a 30-day notice. “We saw the writing on the wall with the land there. We’re just like, it’s a vacant lot in the middle of the city—it’s probably not gonna be there long,” Walker says. “There’s a high-rise there now.”

For years, Walker and Rivera-Chapman had been plotting to pool their resources with friends, including Courtney Woods, an assistant professor of environmental engineering at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and Justin Robinson, a musician and scholar of Southern foodways who was a fiddler for the Grammy-winning Black old-time group the Carolina Chocolate Drops. (In his own off-farm job, Walker works at RAFI-USA, a North Carolina-based rural-justice advocacy group, managing the Farmers of Color Network.) Together they formed the Earthseed Land Collective (the name pays homage to a series of books by the Afrofuturist novelist Octavia Butler) and bought the 12-acre property that houses Tierra Negra. More recently, with a community bank loan and support from a local land trust, they bought an additional 38 acres of adjoining land. Such prime real estate, Walker says, would not have been affordable “if we weren’t able to work through a collective model.”

People pooling resources and buying land for multiple uses “presents one of the most viable options” for young farmers to access land right now, says Noah McDonald, a former Soul Fire apprentice who now works as a researcher at the Southeastern African American Farmers Organic Network. Sharing resources was “functionally how our ancestors were able to acquire so much land in the Southeast in the first place,” he says. Yet efforts like Earthseed take time, and high prices mean that it’s hard for anyone besides midcareer professionals like Walker’s crew to break in.

A Senate bill introduced last year could shake things up dramatically. Introduced in November, the Justice for Black Farmers Act would reverse the “destructive forces that were unleashed upon Black farmers over the past century,” says Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.), who sponsored the bill along with Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.). The legislation would devote $8 billion annually to buying farmland and granting it to Black farmers. The goal: 20,000 grants per year through 2030, with maximum allotments of 160 acres. The bill would also fund agriculture-focused historically Black colleges and universities, provide farmer training, and support the development of farmer cooperatives.

The bill grew out of a letter that Black farmers and advocates had sent to Warren during her presidential campaign in 2019, urging her to directly address racism at the USDA and the loss of Black farmland. One of the signatories was Lawrence Lucas, president emeritus of the USDA Coalition of Minority Employees, who calls the bill “a quantum leap for justice” that confronts the “racism embedded in the USDA since its founding and that has been allowed to control the destiny of Black farmers’ lives.” Penniman, who also played a role in shaping the bill, says, “I never dared to imagine that such an elegant, fair, and courageous piece of legislation as the Justice for Black Farmers Act could be introduced.”

The bill will likely draw opposition from budget hawks and senators opposed to any form of reparations, but it has also been criticized by some food-justice activists. In a widely shared Medium post, Chris Newman, who’s enrolled in the Choptico Band of Piscataway Indians, denounced it as a “bill so loaded with oversights, anti-solidarity, and implied acceptance of settler-colonial agricultural ethics that it can’t even be viewed as incremental progress or a step in the right direction.” Not only is the bill modeled on 19th-century Homestead Acts that handed Native territory to white settlers in allotments of 160 acres, he notes; it also doesn’t address or even mention the epic theft of land.

To be clear, any land that changes hands under the act would be bought by the federal government at market price from a willing seller. But Newman’s critique still resonated with several Black farmer advocates I spoke with. In Black agrarianism, McDonald says, “we grapple with that tension because we come from an Indigenous spiritual home in the deep past.” Black Americans are also “displaced indigenous people” who should act in solidarity with Native Americans. Yet the bill’s “greatest contribution,” he adds, “is that it’s ignited this conversation around Native land sovereignty, homesteading land reform, and land redistribution.”

Jessica A. Shoemaker, a professor at the University of Nebraska College of Law and a scholar of Native American land issues, offers a similar view. The bill “is one step in a longer and desperately overdue reconciliation process in this country, and at least it is a start where there has been nothing for far too long,” she says. “Even having this conversation at the federal level seemed impossible until a few months ago.”

As the bill sat in limbo, another piece of legislation made its way into the $1.9 trillion covid relief bill after a push from senators including Booker and Raphael Warnock (D-Ga.): $4 billion in payments to help farmers of color “pay off outstanding USDA farm loan debts and related taxes” and another $1 billion to fund training and support for them, as well as to confront racism within the USDA.

Tahz Walker stands in a hoop house as collards and kale begin to sprout.

Madeline Gray

Standing under the winter sun, Tahz Walker contemplates the future of Tierra Negra Farm. For the past four years, he and Rivera-Chapman have focused on building infrastructure like covered growing spaces that extend the season into the cold months, and a greenhouse that will free them from relying on a commercial nursery and provide “more control over varieties that we grow.”

That has them contemplating growing special crops just to harvest and sell the seeds, opening another income stream while providing the region’s farmers and gardeners with traditional varieties like cabbage collards, a light-green North Carolina heirloom that Walker grew for the first time last year. “Doing the math, it looks like we could grow out cool varieties, have food and eat it, and still sell it,” he says. He’s still figuring out the details. Like the Black agrarian movement, Tierra Negra remains a work in progress, seeding a brighter future in the fertile soil of a complicated past.