valentinrussanov/Getty

Sen. Joni Ernst (R-Iowa) normally doesn’t see climate change as a major societal threat in need of a policy response. A magnet for agribusiness and oil-industry campaign contributions, she pleaded ignorance about climate science at a debate in 2014. She added, “I can’t say one way or another what is the direct impact, whether it’s manmade or not. I’ve heard arguments from both sides.” Yet Ernst has managed to find a piece of climate legislation she likes—one that involves one of her state’s major industries: agriculture.

It’s called the Growing Climate Solutions Act, and Ernst counts among 49 senators on both sides of the partisan divide sponsoring it. Outside supporters include the National Milk Producers Federation, the National Pork Producers Council, and the United States Cattlemen’s Association. The American Farm Bureau Federation, an insurance conglomerate and agribusiness lobbying powerhouse that has long opposed federal regulation to cut greenhouse gas emissions, is pushing it, as is the US Chamber of Commerce, a champion of unfettered oil and natural-gas drilling.

Some Big Green groups back it, too. “Passage of the Growing Climate Solutions Act would be a big win for agriculture, conservation, and the climate,” argued a recent statement from the Nature Conservancy, echoing similar enthusiasm from the Environmental Defense Fund. In late April, the bill sailed through the Senate Agriculture Committee, and likely has the votes to pass the full Senate, although it has yet to be scheduled for a vote.

What policy intervention could magically align these disparate forces behind climate action? And does its broad appeal represent a nascent urge among GOP stalwarts like Ernst and polluting industries like Big Ag to take the challenge seriously?

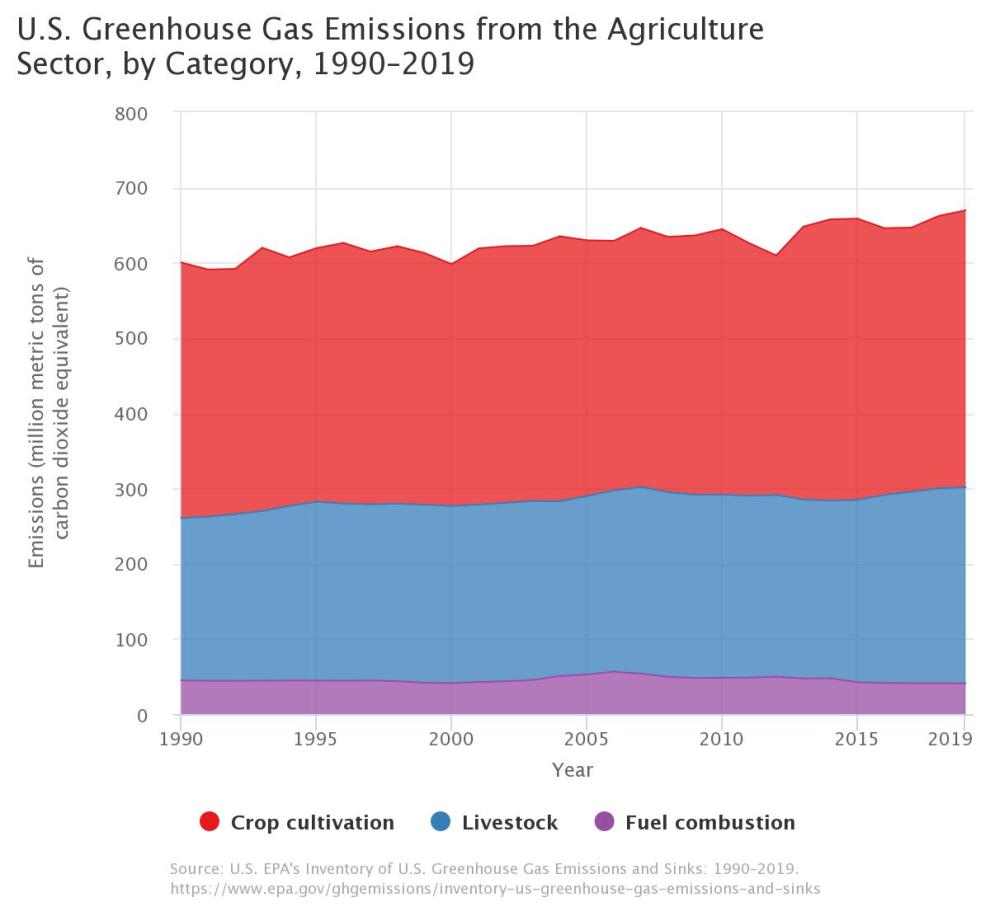

No doubt, cutting greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture, and fast, will be vital to fending off the worst ravages of climate change. Farms contribute just 10 percent of total US emissions, but the situation is worse than it looks at first glance. Overall US emissions have been edging downward since peaking in 2007, albeit not nearly rapidly enough. We’re now spewing heat-trapping gases at an annual rate just 1.9 percent higher we did in 1990, the Environmental Protection Agency reports. Greener electricity generation—more wind and solar, less coal—drives the downward trend. But over the same period, ag-related emissions have steadily drifted upward, rising 11.7 percent since 1990.

The Growing Climate Solutions Act turns out to be a pretty small-bore response to this growing problem. It mandates no emissions cuts or any new regulations. Instead it directs the US Department of Agriculture to “develop a program to reduce barriers to entry for farmers, ranchers, and private forest landowners” to participate in voluntary private carbon markets.

Carbon markets work like this: Say a farmer opts for techniques that suck up carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it in the soil (see my 2013 piece on Ohio cover-crop/no-till evangelist David Brandt, who has developed a system for doing just that). In a functioning carbon market, the farmer could sell what’s called a “carbon credit” for the stored carbon to a polluting company—say, an oil driller. The farmer gets a payment; the drilling company gets to boast a cut in its “net” emissions, earned with the payment, without having to change its own practices. Such credits can be flaunted to appease the growing set of shareholders demanding that polluting companies cut their emissions; or simply to generate good PR as the ravages of climate change pile up. The goal of such agricultural “offsets,” as they’re known, is to incentivize climate-friendly farm practices, like Brandt’s.

Private carbon markets for agriculture already exist, but they have not exactly taken farm country by storm. The most prominent one, run by a company called Indigo Agriculture (profiled by my colleague Maddie Oatman here), has so far managed to enroll farms representing 2.7 million acres into its program, Reuters recently reported. That’s a tiny fraction of US farmland; the four most prolific US crops—corn, soybeans, wheat, and cotton—cover about 239 million acres. Genetically modified seed and pesticide giant Bayer Crop Sciences (formerly Monsanto) runs a rival carbon program; and a cluster of Big Food and Big Ag companies, including McDonald’s, Cargill and General Mills, plans to roll out yet a third, the Ecosystem Services Market Consortium, in 2022.

Indigo, Bayer, McDonald’s, Cargill, and General Mills have all endorsed the Growing Climate Solutions Act, in hopes that getting the USDA stamp on private ag-based carbon markets will draw in more buyers, and ultimately more farmers willing to adopt practices that qualify for credits. The bill calls on the USDA to provide guidelines for which practices reduce greenhouse gas emissions or sequester carbon; and for entities like Indigo and the Ecosystem Services Market Consortium to “self-certify” with the department by claiming expertise in measuring ag-related climate benefits and providing technical assistance to farmers for attaining them.

And that’s pretty much it. In short, if the act passes, the USDA will provide its imprimatur—in the form of a “USDA-certified” designation—on private markets that are already functioning, though currently at low level.

Not everyone is as convinced that voluntary markets managed by private players like Bayer and Indigo can push US farms in more climate-friendly directions, even with USDA guidance. Ben Lilliston, director of rural strategies and climate change at the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, a Minneapolis-based think-tank, notes that rigorous market-based climate action requires carrots and sticks: not just payouts for operations that sequester carbon or cut pollution, but also ever-stricter limits on overall greenhouse gas emissions—which the Growing Climate Solutions Act lacks.

In a classic cap-and-trade scheme, the government mandates an economy-wide cap (limit) on emissions. The cap then drops over time. Companies that can’t comply—say, ones drilling for crude oil, running coal-fired power plants, or methane-spewing cattle feedlots—would be compelled to buy carbon credits to offset a portion of their emissions. As the carbon cap continued to drop, offsets would get more and more expensive, forcing polluting companies to adopt less GHG-intensive business models or go bankrupt. That’s the theory, anyway. Lilliston notes that California has had a pioneering cap-and-trade system in place since 2013, and the state’s powerful oil and gas industries have still managed to continue spewing greenhouse gases largely unimpeded. Meanwhile, a blockbuster recent ProPublica report showed that the system may be significantly overestimating carbon-sequestration rates for some forest-based projects that have drawn $1.8 billion worth of credits. But with no cap at all in place, there’s no real lever to force polluters to buy credits, Lilliston points out.

“Even if you’re true believer in market-based solutions, to create an offset market without a carbon cap—that makes no sense,” he says. “There’s no chance that the carbon-credit price will ever really rise, because polluting companies don’t have to buy these offsets.” Currently, the price of an offset stands at around $15 per ton of carbon equivalent. At that level, some big companies may opt to buy offsets to burnish their reputations, Lilliston says. (Reuters cites IBM, J.P. Morgan Chase, and Barclays as current buyers of ag offsets.) If the price of the offset gets to $40 or $50, he says, “they can just say, ‘screw it,’ and stop buying offsets, or buy them from another part of the world where they’re cheaper.” Then the US carbon price would drop, and we’d be back to where we are now: a little-used carbon market doing not much at all to impede ever-growing US GHG emissions on farms.

Lilliston notes that this precise scenario played out in the 2000s, when a project called the Chicago Climate Exchange sold carbon credits, including ones generated on farms, into a market with no emissions cap. It ended up collapsing in 2010 due to a lack of buyers. In short, without strict limits on emissions, a carbon market represents an opportunity for polluting industries to launder their reputations, but doesn’t push them to change their ways.

Silvia Secchi, a natural resource economist at the University of Iowa, says voluntary carbon markets have other problems as well. These schemes “do not fundamentally challenge, for example, livestock—it’s becoming more and more apparent that really, policymakers don’t want to touch that,” she says. The US meat industry is a massive contributor to US agriculture’s greenhouse gas footprint, EPA data show. Methane, a gas with 25 times the heat-trapping power of carbon, spews from livestock farms in two ways: from the digestive system of cattle (mainly in the form of burps) and from vast manure stores outside of factory-scale beef, dairy, hog, and chicken farms. Between 1990 and 2017, as US livestock farming has concentrated into ever fewer and larger operations since 1990, manure’s methane footprint surged 66 percent, according to the EPA. The meat industry’s manure problem is unlikely to be resolved without regulation that forces farms to stop polluting, Secchi says.

The prospect of climate legislation brimming with carrots and lacking sticks may be exactly why the meat industry welcomes the bill. “We believe that farmers, ranchers, and producers are the mainstay of the agriculture industry and play an essential role in reducing global greenhouse gas emissions,” wrote John R. Tyson, Chief Sustainability Officer at Tyson Foods, the globe’s second largest meat company, in an email. “The Growing Climate Solutions Act of 2021 is a great move in the right direction, and we commend the bipartisan work to address climate change.”