Digital Vision./Getty

For about $7—less than an hour’s minimum wage—McDonald’s will dish up 1080 calories in the form of a Big Mac, some fries, and a soda. Taco Bell offers an even more enticing proposition: Its beef-laden “Grande Crunchwrap Meal” delivers 1290 calories for just $5. For years, critics of the US food system—Eric Schlosser, Michael Pollan, Raj Patel, Leah Penniman, Frances Moore and Anna Lappé, Marion Nestle, others—have warned that such deals are actually no bargain when you add in the hidden costs. Those include poverty wages for workers from the farm field to the franchise counter; precious topsoil surrendered to the growing corn and soybeans for cattle feed; greenhouse gases and other deadly pollution emanating from livestock feedlots; widespread misery from diet-related diseases like Type 2 diabetes and heart conditions; and more.

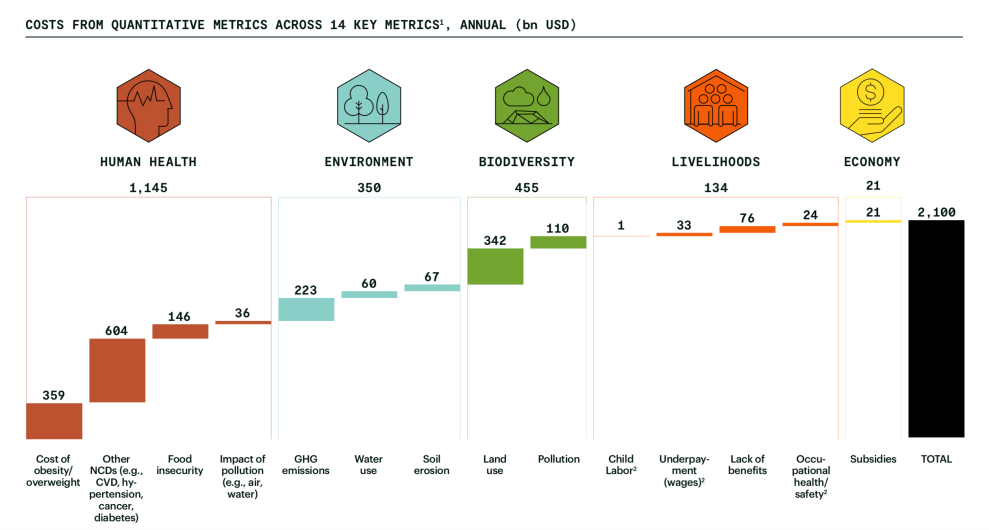

A new Rockefeller Foundation report adds heft to the concerns about the high costs of cheap food. The United States boasts the “most affordable food in the world,” the foundation’s researchers found. But this cheap fare hides some dirty secrets. The authors dug into 14 metrics—most prominently, health, environment, biodiversity, and livelihoods—to quantify “externalized” costs that aren’t covered by the price of food.

Altogether, we spend $1.1 trillion feeding ourselves every year; and we rack up at least another $2.1 trillion in expenses that don’t show up in the prices we pay—or on the profit/loss statements of the corporate giants that dominate the food system. (The researchers stress that they took a conservative approach in compiling its assessment of the “true cost of food,” using only data from widely cited reports.)

Here’s how the data broke down (numbers are in billions of dollars):

Diet-related healthcare costs came in $1.145 trillion annually, about equal to our total food expenditure. That means that for every dollar we spend feeding ourselves, we generate at least another dollar in insults to public health. Non-communicable conditions, like obesity and hypertension, make up the bulk of these expenses. “If diet-related disease prevalence rates were reduced to be comparable to countries such as Canada, health care costs could be reduced by close to $250 billion per year,” the study found.

Food insecurity, reckoned at $146 billion annually, is another eye-popper. US inequality is so stark, and poverty rates so high, that even though we have the globe’s most affordable food supply on average, 10.5 percent of US households—and 13.5 percent of households with children—find that their “their access to adequate food for active, healthy living is limited by lack of money and other resources,” to use the USDA’s food-insecurity definition.

Not surprisingly, the public-health harms of our food system fall hardest on historically marginalized groups. Black and Latinx Americans are diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at rates 1.5 and 1.7 times higher than their white counterparts; and are also much more likely to be exposed to toxic agrichemicals and air pollution from farms, the researchers found.

And we rack up another $805 billion in environmental and biodiversity destruction with our annual food expenditures—another 80 cents for every dollar we shell out—for everything from greenhouse gas emissions from manure ponds to polluted water and air in agriculture-intensive regions like Iowa, the center of US corn, soybean, and hog production. Indeed, Iowa is a microcosm of the dysfunctions laid about by the Rockefeller Foundation report. The state’s farm fields are the site of a slow-moving, devastating soil-erosion crisis; chemical and manure runoff from them routinely pollutes water; and they’re ultimate source of much of the processed and fast foods that triggers all of these diet-related diseases. The kicker: Rather than face regulation from the federal government, Iowa farmers draw subsidies, to the tune of more than $35 billion between 1995 and 2020.

I explored some of these themes in my 2020 book Perilous Bounty. Here’s a sample.

As for the cuisine that grows from transforming corn and soybeans into cheap meat, sweeteners, fats, and processing agents, it’s hardly recipe for robust health and longevity. Nearly 60 percent of the calories Americans consume come from the very “ultra-processed” foods that are shot through with corn and soybean derivatives. On any given day, about 37 percent of Americans have at least one meal from a fast-food chain—another industry puffed up by the Corn Belt’s bounty (think corn-and soybean-fed beef, corn-sweetened soda, potatoes fried in soybean oil). It’s no wonder that “nearly half of all American adults have one or more chronic diseases that are related to poor quality diets,” a 2017 study by National Cancer Institute researchers reported. The so-called western diet—the culinary manifestation of the corn/soybean duopoly—is a harbinger of such diet-related distress, and researchers have documented that as it spreads across the globe, it leaves a pandemic of diabetes, obesity, and heart disease in its wake.

In short, our country’s gargantuan corn and soybean crops, concentrated in Iowa and surrounding states and occupying more than half of U.S. farmland, are essentially a zero-profit industry for farmers, propped up by billions in government payouts. The main beneficiaries are a set of interlocking, enormous corporations, each generating billions of dollars for shareholders and delivering in exchange a mountain of health-ruining food.

The Rockefeller Foundation report doesn’t lay out much in the way of solutions to the wreckage being generated by our food-production regime. Instead, it provides a stark frame for thinking them through. “Realizing a better food system requires facing hard facts. We must accurately calculate the full cost we pay for food today to successfully shape economic and regulatory incentives tomorrow,” the introduction states. In a summer of cascading climate mayhem, I can’t think of a more urgent task.