A vendor balances a tray of Egyptian traditional "Baladi" flatbread as he cycles in Old Cairo district, Egypt, in March 2022. Amr Nabil/AP Photo

At the end of 2021, the globe was already teetering on the edge of a hunger crisis. Food prices had hit their highest levels since 1975, according to the United Nations’ index, and at least 768 million people worldwide struggled to find enough to eat. Then came Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, an all-out war in a region that sits at the center of the global trade of a crucial staple crop (wheat), fertilizer, and fossil fuel.

Now, surging prices of these resources are creating an unprecedented “triple whammy” for the world’s economically vulnerable people, said Tim Benton, director of Environment and Society Programme at the London-based think-tank Chatham House, at a recent press briefing. Things were already dire on all three fronts before the war started, he said. “Driving up the price of fertilizer, energy, and food, in independent and interconnected ways, means that people will suffer.”

Here’s a closer look at how the pandemic and the Russian invasion are ramping up hunger:

Food prices soared

Before the Russian invasion, food prices were already rising due to gyrations in the natural gas market caused by the coronavirus pandemic. Shutdowns in 2020 had slashed demand for the fuel. Then in 2021, as people in northern countries got vaccinated, economies reopened and natural gas use surged again. Producers had to scramble to boost output in response, leading to supply chain glitches that sent prices spiraling upwards.

Natural gas is the fuel of choice for the manufacture of nitrogen fertilizer, the synthetic soil nutrient that serves as the lifeblood of industrial agriculture. Farmers from the American Midwest to Brazil’s savanna to China’s breadbasket to Ukraine’s “black earth” region rely on nitrogen fertilizer. When natural gas gets more expensive, so does this fertilizer—and global food prices typically follow.

Wheat went missing.

When Russia invaded Ukraine, it dragged its western neighbor into a chaotic war right on top of one of the globe’s most important wheat-growing regions and trade routes. Russia and Ukraine make up nearly a third of the world’s wheat exports. Since rumors of war began swirling in mid-February, wheat prices have jumped by about a third, and as of March 30, a ton of wheat on the global market costs 70 percent more than it did a year ago. Throughout the Middle East and North Africa, bread, couscous, noodles, and other wheat-derived foods anchor people’s diets. No country will be hit harder than Yemen, already ravaged by a sustained war with US-backed Saudi Arabia. There, more than half of the nation’s population of 29.8 million people faced food insecurity at the end of 2021, according to the World Food Program.

When the price of one major staple crop jumps, others typically move with it. The price of corn—a livestock feed crop in the United States and China, and a food staple in Mexico, Central America, and much of sub-Saharan Africa—is up 13 percent since mid-February and 32 percent since late March of last year. Rice, too, is on a tear in global markets.

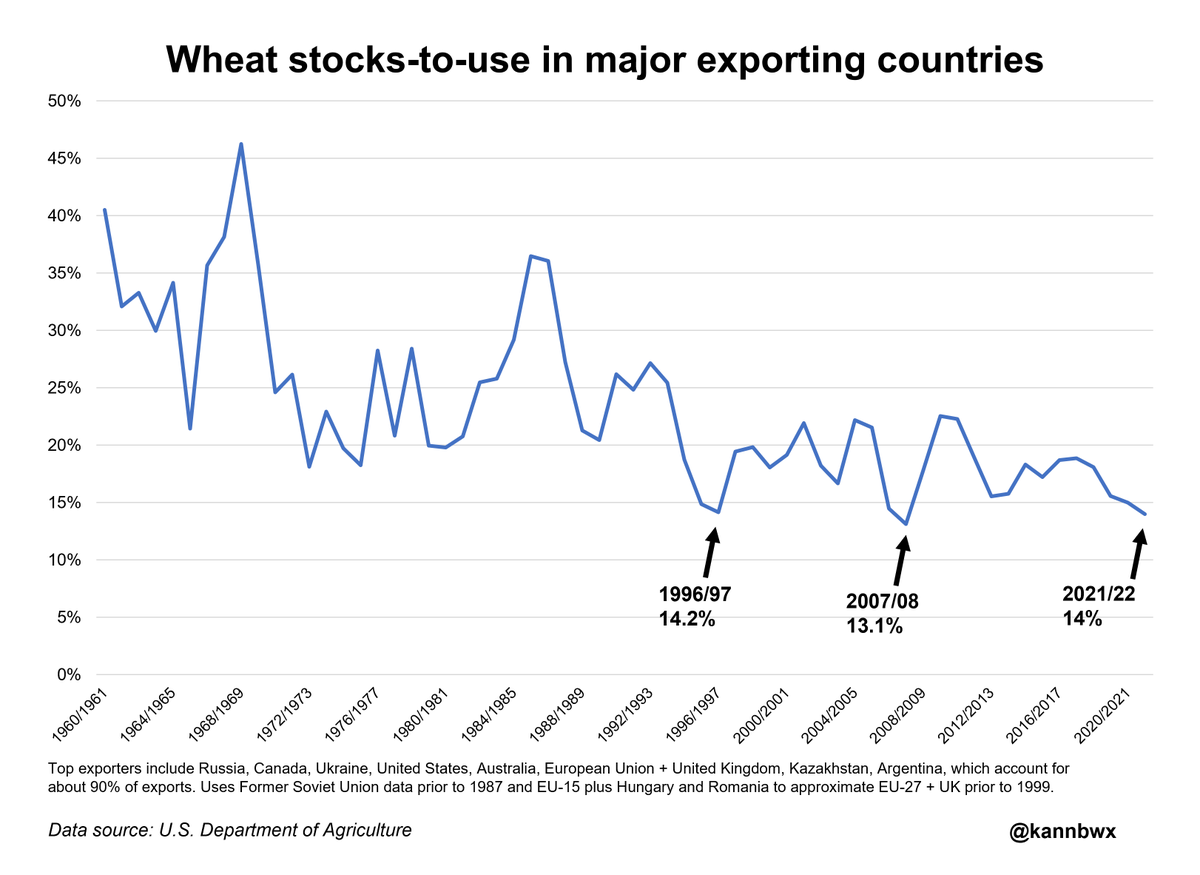

The disruption of Russian and Ukrainian wheat shipments—and a likely decline in plantings of spring wheat in Ukraine—comes at a time when the biggest wheat producers and exporters were already holding very little excess grain in storage for a rainy day. To gauge how much wheat is stored in silos, providing a buffer from supply shocks like the current war, analysts look at what’s called the “stocks-to-use ratio”—the amount of grain held in storage at year’s end divided by the amount consumed over the same period. When the stocks-to-use ratio plunges, that essentially means the world’s wheat pantry is bare—and prices are prone to rise if there’s a bad harvest or other disruption in a major producing region.

On Twitter, Reuters global agriculture columnist Karen Braun recently brought sobering news about the state of wheat storage before the invasion. Here’s the chart she posted. Note that wheat stocks have dipped to their second-lowest level of the past 60 years.

Fertilizer production flagged

Halting the flow of wheat out of Ukraine’s ports isn’t the war’s only dire consequence for the world’s poor. Russia produces about 17 percent of the globe’s natural gas, and is by far the world’s biggest exporter of the fossil fuel. War-related trade disruptions and sanctions against Russian exports have led to another round of spikes in natural gas prices—and pricier natural gas means pricier nitrogen fertilizer. Already, European nitrogen-fertilizer makers, who are reliant on Russian gas imports, have cut back on production in response to higher costs, reports Samuel Taylor, a farm-inputs analyst for agriculture-finance firm Rabobank.

To make matters worse, Russia is itself a major producer and exporter of both nitrogen fertilizer and another crucial mineral fertilizer, potash. “Massive amounts” of Russian-made fertilizer typically head to global markets through Ukraine’s Black Sea ports, Taylor said, and “that route has effectively been shut down” by the war.

Accordingly, prices for crop nutrients are surging, at the precise time farmers in northern-hemisphere regions are preparing for spring planting. And that jump will likely feed into higher food prices for a while, because farmers often respond to hikes in fertilizer costs by planting fewer acres or applying less fertilizer, which can pinch yields.

Poor countries won’t be the only victims of this hunger crisis, Benton explained. Residents of rich countries like the United Kingdom and the United States will feel the impact, too. According to the latest US Department of Agriculture data, from 2020, 10.5 percent of US households—and 7.6 percent of households with children—struggle to put enough food on the table. And that was before the current jump in food prices. These same households are now having to spend more on gasoline and home heating.

Just as the jump in fossil fuel prices—and the power wielded by the leaders of petrostates like Russia—suggests the need to transition to renewable energy sources like wind and solar, the dawning food crisis suggests a need to change the global food system, said Jennifer Clapp, a professor at the University of Waterloo who serves as vice chair of the High-Level Panel of Experts for the UN Committee on World Food Security. “The war in Ukraine has revealed the dangers of relying on a handful of major exporting countries for global food supplies,” she said.

For decades, policymakers at institutions like the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank have pushed low-income countries to focus their farming regions on pricey export crops for rich-country markets, and to import staples like wheat and corn. “We must make food systems more resilient to ensure the next shock—whether from conflict or climate change—does not spark another crisis,” Clapp urges. One way to do that is by investing in domestic production across the world.

And to reduce vulnerability to shocks in the fertilizer market, farmers can be urged to lean on the nitrogen-fixing power of legume crops. A team of researchers from Iowa State University has found that by adding legumes like clover and alfalfa to the classic corn-soybean rotation in the US Midwest, for example, farmers slash fertilizer without reducing overall yields.

But these responses won’t immediately fix a mounting hunger crisis. With markets roiled with no end in sight, she said, mobilizing emergency food aid to avoid a sharp spike in hunger “is the number one priority.” Failure to do so will likely beget a fresh surge of violence. As University of Georgia food-commodity historian Scott Reynolds Nelson recently told me, “When we see tanks in Ukraine, it won’t be long before we’re going to see tanks in lots of other places.” He added, “But not for invasions—tanks being used against people who are rioting in the streets.”