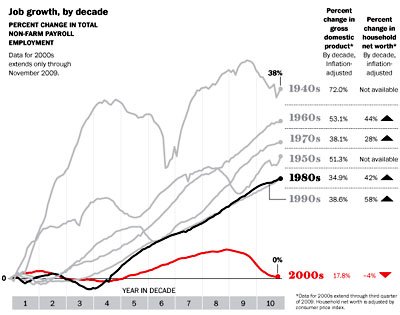

Why were so few jobs created during the aughts? In net terms no jobs at all were created, but even if you exclude the post-bust years the aughts saw a net increase of only 7 million jobs compared to 22 million in the 90s. What happened?

Well, computerization may have played a role. Globalization too. Or maybe low federal spending on pure R&D. But in the current issue of the Washington Monthly, Barry Lynn and Phillip Longman finger an additional suspect. The problem, they note,  wasn’t a rise in job destruction, which was actually lower than in the 90s, but a lack of job creation. And the engine of job creation is small businesses.

wasn’t a rise in job destruction, which was actually lower than in the 90s, but a lack of job creation. And the engine of job creation is small businesses.

So why did small businesses stop prospering in the aughts? The answer they propose is a new one: consolidation. Starting in the early 80s, as the Reagan administration decided to quit enforcing antitrust laws, big companies began merging in earnest, and by the early aughts it was common for three or four firms to control upwards of half or more of entire sectors. It happened in retail, it happened in banking, it happened in pet food, it happened nearly everywhere. And not only do big firms innovate less than small firms, they also prevent innovative small firms from ever getting a chance to grow in the first place:

Dominant firms can hurt job growth by using their power to hamper the ability of start-ups and smaller rivals to bring new products to market. Google has been accused of doing this by placing its own services—maps, price comparisons—at the top of its search results while pushing competitors in those services farther down, where they are less likely to be seen—or in some cases off Google entirely. Google, however, is a Boy Scout compared to the bullying behavior of Intel, which over the years has leveraged its 90 percent share of the computer microchip market to impede its only real rival, Advanced Micro Devices, a company renowned for its innovative products. Intel has abused its power so flagrantly, in fact, that it has attracted an antitrust suit from New York State and been slapped with hefty fines or reprimands by antitrust regulators in South Korea, Japan, and the European Union. The EU alone is demanding a record $1.5 billion from the firm.

To understand just how disadvantaged small innovative companies are in markets dominated by behemoths, consider the plight of Retractable Technologies, Inc., of Little Elm, Texas. The company manufactures a type of “safety syringe” invented by its founder, an engineer named Thomas Shaw. The device uses a spring to pull the needle into the body of the syringe once the plunger is fully depressed. This helps to prevent the sort of “needlestick” injuries that every year result in some 6,000 health workers being infected by diseases such as hepatitis and HIV. Since starting the company in 1994, Shaw has carved out a modest market niche, selling his lifesaving product to nursing homes, doctors’ offices, federal prisons, VA hospitals, and international health organizations for distribution in the Third World. But he’s not been able to break into the mainstream U.S. hospital market. The reason, he says, is that a company called Becton Dickinson & Co. controls some 90 percent of syringe sales in America and enjoys enough power over hospital supply purchasing groups to all but block adoption of Shaw’s device. In 1998, Shaw sued, charging restraint of trade, and in 2004 won what looked like a stunning victory: Becton Dickinson agreed to settle for $100 million, and the purchasing groups promised to change their business practices. But according to executives at Retractable Technologies, things have only gotten worse. “We probably have less of our products in hospitals today than we did ten years ago,” says Shaw, who just won a patent-infringement case against Becton Dickinson and is pursuing another antitrust suit against the company. “I have spent what should have been the most creative, productive years of my life sitting in depositions. By the time I’m done fighting, my patents will have expired.”

A few years back, Bess Weatherman, the managing director of the health care division of the private equity firm Warburg Pincus, spelled out the effect of such monopoly power on investments in new health care technologies. In a Senate hearing, Weatherman testified that “companies subject to, or potentially subject to, anti-competitive practices … will not be funded by venture capital. As a result, many of their innovations will die, even if they offer a dramatic improvement over an existing solution.”

The job growth of the 80s and 90s, Lynn and Longman suggest, was largely powered by companies that were founded in the 70s — companies like Apple, Microsoft, Oracle, and Genentech. By the time the 2000s rolled around, consolidation was largely complete and the pipeline of small, innovative companies was drier than it had been in decades.

They don’t pretend that this is the sole explanation for the jobless aughts, or even that they’ve proven their case. “As we’ve noted,” they say, “there are other [theories] having to do with changes in technology and international trade. These other theories are open to debate, but at least they’re being debated. What isn’t getting talked about is the role industry consolidation might be playing in all this. That needs to change.”

I agree. One of the pathologies of modern conservatism — a pathology that’s shared more often than I’d like by mainstream liberals — is that they’re pro-business, not pro-free market. The difference is critical. Pro-business means passing laws that your business pals like, and as economists since Adam Smith have observed, what businessmen mostly like is lack of competition. The operation of a true free market, conversely, depends crucially on competition and plenty of it. And just as crucially, that requires government intervention to prevent a few behemoths from taking over every sector of the economy. Keeping a free market free takes a lot of work.

If Lynn and Longman are right, we need to start doing that work again. It’s time for economists to start seriously debating whether our sputtering job machine is due in large part to our love affair with big business.