Nobody’s reading the blog today, right? So that makes it a good time to revisit a topic at great length that’s politically out of the question and will never happen.

I’ve always been open to the idea of means testing Medicare, and a few days ago I suggested a different way of doing it: after death instead of before. For each Medicare recipient, keep a running tally of the cost of their care, and when they die deduct the premiums and copays they’ve been responsible for. What’s left over gets taken  out of their estate, the same way back taxes would. Rich people would end up paying their entire bill, poor people with no estates would end up paying nothing, and those in the middle would pay a portion that depends on how big their estate is. Will Wilkinson wasn’t impressed:

out of their estate, the same way back taxes would. Rich people would end up paying their entire bill, poor people with no estates would end up paying nothing, and those in the middle would pay a portion that depends on how big their estate is. Will Wilkinson wasn’t impressed:

I’ve got a better idea. Don’t give the elderly rich any government money for health care. Let them pay for it, because they’re rich! And give other seniors just the assistance they need—no more, no less—to buy a health plan of a certain minimum level of coverage. Now, I know this is a fantastical idea for crazed, science-hating, Rand-thumping Jacobins, amounts to destroying Medicare as we know it, and is good for nothing but losing elections. But for all that it seems at least as practical as picking over dead peoples’ estates.

That phrase — “picking over dead peoples’ estates” — is, of course, the Achilles’ heel of my proposal, since that seems to be the instinctive reaction of just about everyone to the idea of allowing the government first crack at estates. Still, let’s put that aside for the moment. Is means testing of living people really as practical as means testing dead people, as Will suggests? I don’t think it is.

First off, let’s review Welfare Economics 101. The problem with means testing — any means testing — is that it acts like a gigantic tax on earnings. Suppose, for example, that you receive $5,000 from the government if your income is below a certain level. If you start earning more, your benefits go down. Maybe the income threshold is $10,000, and for every $1,000 above that you lose $500 in benefits. Do you see the problem? It’s like a 50% tax on everything you earn over $10,000, and that reduces the incentive to work hard and earn more.

This is a well-known problem with all means-tested programs, and there’s no ideal solution to it. You just have to muddle through. The Medicare version of this is that means testing would reduce the incentive to work and save while you’re young. Why bother if it’s just going to get eaten up by Medicare expenses later in life? Why not live for the moment, keep your income below the means-testing threshold, and then take advantage of free Medicare when you’re old?

Beyond that, there’s the problem of how to means test and what the threshold should be. Will says that we should give people “just the assistance they need,” but that’s not as easy as it sounds. Should means testing be done on income or wealth? If it’s income, then you’re giving away benefits to people who might have modest retirement incomes but lots of assets. Why should they be allowed to keep their expensive homes and cars and boats and stock portfolios while Uncle Sam pays for their hip replacement? But if you means test on wealth, then you force people to impoverish themselves before they qualify for care. Do you want to be the one to tell granny that she has to sell her house and all her belongings before she gets a dime from the government? I didn’t think so.

Well, how about just limiting means testing to the genuinely rich? If you have a retirement income of $200,000 and $10 million in assets, then you can certainly pay for your own medical care. No argument there. The problem is that the genuinely rich only account for about 2% of the population. Maybe 5% tops. Sure, you can make them pay for their own care, but it’s not going to make much of a dent in Medicare spending. So why bother?

So now consider my idea. You can earn and save money in your youth and know that you’ll still have it in your old age. You can spend it as you like. We don’t need any complicated formulas for figuring out who qualifies for free Medicare and who doesn’t. We don’t need to impoverish granny and take away her house.

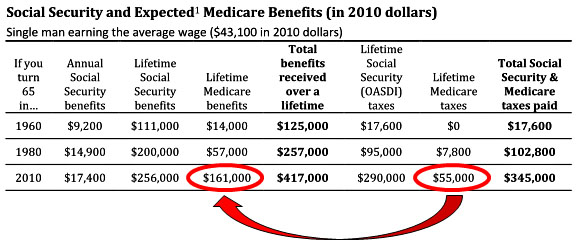

Instead, we just keep track of what you spend and then take it out of your estate when you don’t need it anymore. Will people try to hide assets or give them away in order to avoid Uncle Sam’s bite? Sure. But think about this for a moment. The average cumulative Medicare bill after you’ve died will be on the order of $100-200,000. The really rich, who have the means and the legal talent to do fancy estate planning, aren’t going to run down their estates below that amount. It’s just too piddling, and they want to have at least a few millions unencumbered by legal chicanery throughout their lives. Conversely, the working and middle classes mostly don’t have the ability (i.e., money for expensive lawyers and estate planners) to cheat their way out of this. That leaves the upper middle classes, and they’ll probably try to evade some of their Medicare expenses. But that’s a relatively small number of people — and without minimizing the problem here, it really is possible to regulate a lot of it away. If Medicare had first claim on estates the same way the IRS does, it would mostly get all the money owed to it. Just giving them first claim on homes would go a long way toward keeping things kosher.

This doesn’t completely get rid of the Welfare 101 problem, of course. There’s still a certain amount of disincentive to earn and work while you’re young, knowing that you can’t bequeath every last dime of your money to whoever you want to. But the disincentive is a lot less. Your parents love you and all that, but guess what: they mostly love themselves even more. They’ll do a lot more to protect their own access to their wealth than they will to protect yours.

To some extent, of course, all I’ve done is shift the problem: there’s now an incentive to spend all your money not during your working years but during retirement. Why not, if it’s all just going to Uncle Sam after you die anyway? There’s no question this will happen, but my guess is that it will happen less you might think. I don’t know if there’s any empirical evidence on this score (how would you get it?), but there’s a limit to how much people want to spend down their wealth. Mostly they don’t want to sell their houses while they’re still alive, for example, and if they’re the saving types they probably want to keep a certain amount of their savings around no matter what. Besides, if you means test Medicare, this incentive to spend down your savings during retirement exists regardless of whether the bill comes due before or after death.

So, roughly speaking, that’s my case. Charging for Medicare expenses after death solves the problem of trying to figure who deserves what and how much you can afford. We just don’t bother. We simply tot up the charges and then take it out of your estate. If there’s no estate, that probably means you were poor and couldn’t have afforded to pay for it in the first place. If there’s a big estate, it means you were rich and can pay for 100% of your Medicare costs. And for the middle classes, which are by far the trickiest for any means testing policy, it allows effective means testing that, almost by definition, takes from you only money that you can truly afford to pay.

There is, of course, no reason this has to be a standalone policy. We still need to rein in the growing costs of Medicare no matter what. You might also want some pretty strict rules about what you can do with your money if you’re currently in a nursing home being paid for by Medicare or Medicaid. (Though the rules on this are already pretty strict in a lot of states, which really do require you to impoverish yourself before you qualify for aid.)

But still: this would almost certainly raise a huge amount of money. It would raise it not based on what you might use in the future, but on what you’ve actually used during your life. And it would raise that money from people who don’t need it anymore.

Let me repeat that: It would raise the money from people who don’t need it anymore. If you want to think of this in ghoulish “picking over dead peoples’ estates” terms, you can. But it’s not. What it is is charging people for a service based on whether they can afford it; it’s allowing them to live their actual lives free of fear and impoverishment; and it’s settling an account the same way that anyone else would who has a claim on an estate. Do you think of a supermarket as ghoulish if they insist that granny’s estate pay for the grocery bill she ran up during her final year of life?

There might be technical reasons that make this unworkable (though I suspect most of them could be resolved tolerably well), but philosophically I just don’t see the objection. It’s fair, it’s efficient, it raises a lot of revenue, and it lets people live their lives decently for as long as they’re alive. What’s not to like?