Last night I mentioned briefly that Socialist François Hollande had most likely won the French presidential election not because the French public had suddenly lurched left, but because incumbents usually lose when the economy is in bad shape. In Greece, however, the mainstream parties have all banded together in a government of national unity. So  how do you vote against the incumbents when every major party is an incumbent? Like this:

how do you vote against the incumbents when every major party is an incumbent? Like this:

Greece was plunged into political uncertainty on Sunday after voters bolstered the far left and neo-Nazi right in a wave of protest that saw the crushing defeat of the dominant political parties they blame for Greece’s economic collapse.

The center right party got 19% of the vote and the Socialists got 14% of the vote. That’s only a third of the total. The radical left got 17% of the vote and the far right got 7%. A couple of dozen other parties split the rest. What happens now is anyone’s guess, but Matt Yglesias makes a good point that Greece, unlike some of the other troubled countries in Europes, lacks any real options:

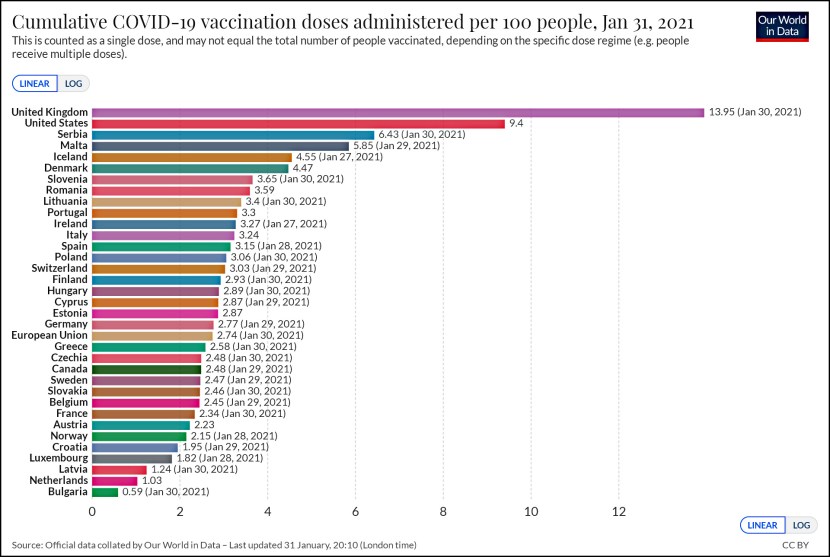

Greece, which lied to qualify for the Euro and then kept on borrowing money by fudging the numbers, is receiving cold hard cash as part of a failed earlier effort to avoid “contagion” to other European countries. If Greece tried to exit the [euro]—or more likely was forced out by Spain or Italy cutting the cord—they’d be in for a dose of much more severe austerity. Think about Greek living standards converging with Serbia and Bulgaria. Many ills can be laid at the doorstep of the fundamental conceptual flaws in the Euro and many others can be laid at the feet of the leaders of the European Central Bank. But Greece’s basic problem really does come down to the fact that the Greek state doesn’t have nearly as much money as it said it had, and there’s absolutely no politically or socially appealing way to acknowledge those losses.

Greece really is a ward of the European state at this point, and no matter how angry the voters get, that’s not going to change. If Greece decided to default completely on its debt and exit the euro, it would be faced with even more crippling austerity than it’s facing now. It’s still possible that this would be the right thing to do in the long run, but make no mistake: in the short run it would have devastating consequences. Greece would be completely unable to borrow on global markets, would be cut off from European aid, and would have to slash spending even more than the Germans are demanding right now. It would be a debacle.

Italy and Spain are in a different position. In theory, they could default on their debt, exit the euro, and be in relatively good shape. “Relatively” is doing a lot of heavy lifting in that sentence, but still, it would probably be less than a total catastrophe. But that’s not true for Greece. They’re just plain and simply screwed, no matter how mad voters are at Germany for rubbing their noses in the fact. They might not like the austerity program forced on them by Europe’s technocrats, but right now they don’t have much choice except to hold their noses and put up with it.