I’ve mentioned before my rough-and-ready theory of the 2008 financial crisis:

- Income inequality goes up.

- As a result, earnings of the middle class become sluggish….

- And earnings of the rich skyrocket, a trend reinforced by lower tax rates on both labor and capital income.

- Rich people eventually run out of sensible things to invest all this money in (because consumer demand is sluggish, see #2), so they get stupid.

- Stupid money finances stupid loans to middle-class borrowers who can’t afford them (because their incomes are sluggish, see #2).

-

This all works great until it doesn’t. When it doesn’t, the economy goes kablooey.

This all works great until it doesn’t. When it doesn’t, the economy goes kablooey.

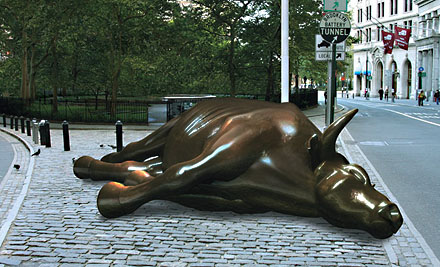

In the aughts, #5 took the form of increasing corruption in the mortgage loan market and increasingly baroque Wall Street financial concoctions to package up all those corrupt loans. It worked great for about five or six years, followed by a Wile E. Coyote moment where the economy was suspended in limbo for a year or so, followed by an epic crash that we still haven’t dug our way out of.

I’m just a blogger, though, so there’s no special reason you should take me seriously. However, a reader alerted me to a recent National Journal piece by Jonathan Rauch that suggests this theory is gaining ground among serious economists:

Once in a while, a new economic narrative gives renewed strength to an old political ideology. Two generations ago, supply-side economics transformed conservatism’s case against big government from a merely ideological claim to an economic one….Something potentially analogous is stirring among the Left. An emerging view holds that inequality has reached levels that are damaging not only to liberals’ sense of justice but to the economy’s stability and growth. If this narrative catches on, it could give the egalitarian Left new purchase in the national economic debate.

….As Christopher Brown, an economist at Arkansas State University, put it in a pioneering 2004 paper, “Income inequality can exert a significant drag on effective demand.” Looking back on the two decades before 1986, Brown found that if the gap between rich and poor hadn’t grown wider, consumption spending would have been almost 12 percent higher than it actually was.

….So inequality might suppress growth. It might also cause instability. In a democracy, politicians and the public are unlikely to accept depressed spending power if they can help it….They might, for example, create policies allowing banks to write flimsy home mortgages and encouraging consumers to seek them….That is not a bad description of what happened in the 1920s and again during these past few years. “When—as appears to have happened in the long run-up to both crises—the rich lend a large part of their added income to the poor and middle class, and when income inequality grows for several decades,” the IMF’s Michael Kumhof and Romain Rancière wrote, “debt-to-income ratios increase sufficiently to raise the risk of a major crisis.”

But wait. Which is it? Does inequality depress demand? Or does it inflate credit bubbles that maintain demand? Unfortunately, the answer can be both. If inequality is severe enough, there could be enough of it to cause the country to inflate a dangerous credit bubble and still not offset the reduction in demand.

And, no, we’re not finished. Inequality may also be destabilizing in another way. “Of every dollar of real income growth that was generated between 1976 and 2007,” Rajan wrote, “58 cents went to the top 1 percent of households.” In other words, for decades, more than half of the increase in the country’s GDP poured into the bank accounts of the richest Americans, who needed liquid investments in which to put their additional wealth. Their appetite for new investment vehicles fueled a surge in what Arkansas State’s Brown calls “financial engineering”—the concoction of exotic financial instruments, which acted on the financial sector like steroids.

The whole thing is worth a read. This model of inequality and financial crises has some powerful proponents, but it’s hardly a mainstream consensus at this point. It’s worth keeping an eye on, though. There might be some serious explanatory power here.