The LA Times opines this morning on the Obama administration’s decision to block a merger between American Airlines and US Airways:

The best illustration of the virtues of deregulation may be the U.S. airline industry, which Congress liberated from most nonsafety-related rules in 1978. The cost of flying plummeted as a host of new players entered the business to compete with the major national airlines.

But as anyone stuck in coach class will tell you, flying isn’t much fun anymore. Airlines cram more people onto planes that offer less legroom. Conveniences that used to be included in the standard ticket price now carry extra fees. And when passengers are stranded by bad weather or mechanical problems, they may be forced to wait hours to find space on later flights that are routinely overbooked.

Such problems could conceivably be solved if competition forced the airlines to pay more attention to customer service.

Hmmm. I’m generally in favor of stronger antitrust action, but I have to admit that the airline industry wouldn’t be my first choice of a hill to die for. I mean, this is an industry that earned a whopping 0.1 percent profit last year—and that wasn’t a bad year. In fact, since 9/11, any year with a nonnegative profit is a pretty good year for U.S. airlines.

That’s why flying in coach is such a miserable experience. It’s because most airlines have been chronic money losers for the past decade and are desperate for ways to increase their revenues. But Osama bin Laden is the culprit here, not consolidation. Frankly, we might all be better off if airlines had a bit more pricing power and could just raise their fares instead of being forced to play all their endless games with seat pitch and baggage fees and so forth.

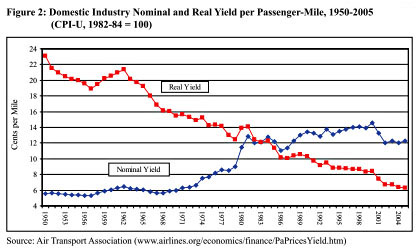

Beyond that, you might be surprised to learn that it’s an open question whether deregulation was such a boon for the flying public in the first place. In a 2007 paper, David Richards looked at airline fares since 1950 and concluded that deregulation accomplished little. Fares had been going down before 1978 and they kept going down afterward. Yield per passenger-mile showed no change before and after deregulation (see chart on right). Growth in passenger miles traveled actually slowed after deregulation, and fares were mostly about the same as they would have been under the old CAB formulas.  His conclusion: “This paper makes clear that the grant of pricing freedom to the airline industry has generally resulted in average prices being higher than they would have been had regulation continued under the DPFI rate-setting policies.”

His conclusion: “This paper makes clear that the grant of pricing freedom to the airline industry has generally resulted in average prices being higher than they would have been had regulation continued under the DPFI rate-setting policies.”

What did happen, Richards found, was that fares decreased on routes between big cities and increased on routes between smaller cities. That may or may not have been a good thing on net, but it’s certainly a far different story than the one we usually hear about deregulation. For more on this, see “Terminal Sickness,” a fascinating look at airline deregulation and the death of the mid-tier market by Phillip Longman and Lina Khan.

This all changed in 2001, when the public stayed away from flying in droves and airlines really did start slashing their fares. But that had nothing to do with either deregulation or consolidation, and in any case, the results have been disastrous. The Obama administration may be right to oppose the American-U.S. Airways merger, but it’s a trickier question than it appears on the surface.