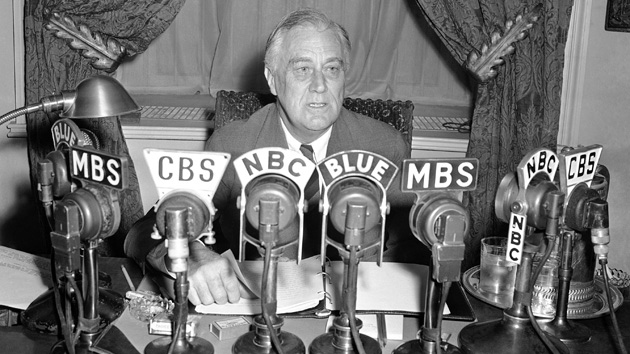

President Franklin D. Roosevelt broadcasts a speech in 1943.George R. Skadding/AP

When was the last time you heard an American politician invoke Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s policies as models to be emulated? Democrats avoid him because his New Deal policies seem to embody the tax-and-spend, overbearing, and intrusive central government that always puts them on the defensive. And why would a Republican bother with Roosevelt when they believe that Obama is so much worse?

Sunday is the seventieth anniversary of FDR’s death on April 12, 1945. Since anniversaries are always good opportunities to reflect on the past, I reread one of Roosevelt’s speeches that I somehow still remember studying in college. It was his penultimate State of the Union Address, which he delivered on January 11, 1944, and the one in which he outlined a “second Bill of Rights”—a list of what should constitute basic economic security for Americans.

The world was still at war. Roosevelt had returned in December from meeting Stalin and Churchill at the Tehran Conference where the three leaders discussed not only the final phase of the war, but also how Europe would be divided after the conflict was over. The worst of the Great Depression was over, remedied in large part by the wartime economy. Roosevelt, who was starting his fourth term and was sick with the flu, decided not to go before Congress. Instead, he delivered the address from the White House. Across the country, people could tune in on their radios and hear their president speak.

Looking at his speech again, I was struck by how he grapples with so many of the same issues that we do now. Here he is on the domination of special interests:

[W]hile the majority goes on about its great work without complaint, a noisy minority maintains an uproar of demands for special favors for special groups. There are pests who swarm through the lobbies of the Congress and the cocktail bars of Washington, representing these special groups as opposed to the basic interests of the Nation as a whole. They have come to look upon the war primarily as a chance to make profits for themselves at the expense of their neighbors—profits in money or in terms of political or social preferment.

And whose interests should our representatives in Congress represent? Roosevelt reminds them:

And I hope you will remember that all of us in this Government represent the fixed income group just as much as we represent business owners, workers, and farmers. This group of fixed income people includes: teachers, clergy, policemen, firemen, widows and minors on fixed incomes, wives and dependents of our soldiers and sailors, and old-age pensioners. They and their families add up to one-quarter of our one hundred and 30 million people. They have few or no high pressure representatives at the Capitol.

Then he gets to the reason for why this is usually referred to as his “Second Bill of Rights” speech.

In our day these economic truths have become accepted as self-evident. We have accepted…a second Bill of Rights under which a new basis of security and prosperity can be established for all regardless of station, race, or creed. Among these are: The right to a useful and remunerative job in the industries or shops or farms or mines of the Nation; the right to earn enough to provide adequate food and clothing and recreation; the right of every farmer to raise and sell his products at a return which will give him and his family a decent living; the right of every businessman, large and small, to trade in an atmosphere of freedom from unfair competition and domination by monopolies at home or abroad; the right of every family to a decent home; the right to adequate medical care and the opportunity to achieve and enjoy good health; the right to adequate protection from the economic fears of old age, sickness, accident, and unemployment; the right to a good education.

Today, many politicians oppose the sorts of policies Roosevelt was suggesting here: the minimum wage, the Affordable Care Act, the expansion of Social Security, and a more generous student loan program. Who would have the nerve to frame them not as hopes, or matters of “fairness” but as basic “rights” that should at least be legislated but possibly even enshrined in the Constitution?

Here is where Roosevelt’s argument gets really interesting. He does not just present this Economic Bill of Rights as a question of fairness or some dreamy utopian ideal of equality. He sees them as a fundamental to national security:

All of these rights spell security. And after this war is won we must be prepared to move forward, in the implementation of these rights, to new goals of human happiness and well-being. America’s own rightful place in the world depends in large part upon how fully these and similar rights have been carried into practice for our citizens. For unless there is security here at home there cannot be lasting peace in the world.

In the decades that followed, Americans became obsessed with national security issues. Any politician can demonize an opponent, curtail some fundamental right, or snag some cash for a contractor by invoking “national security.” But national commitments to economic security for the middle class and the poor are rarely contextualized as national security issues.

At least, not in the United States. Our leaders are quick to connect poverty in other parts of the world with national security concerns. In his introduction to a September 2002 National Security Strategy document, presented a year after the attack on the World Trade Center, George W. Bush stated that, while poverty does not directly lead to terrorism, “poverty, weak institutions, and corruption can make weak states vulnerable to terrorist networks and drug cartels within their borders.”

We tend to look elsewhere for evidence of the dire consequences of poverty and income inequality. But with the Great Depression a very recent memory, Roosevelt knew that what we did in the world mattered less if we did not do the right thing at home. Maybe it’s time to focus on that connection again.