In case you’re wondering, I am now a slave to a chemical clock. A very unpredictable chemical clock. Last night, for no special reason, the Evil Dex kept me up until 4:30 and then didn’t wake me up until 9:30. That’s pretty inconvenient, though it is five hours of sleep, which isn’t too bad. I used the time last night to read one of Elizabeth Warren’s books since it’s increasingly looking like she’ll be the 46th president of the United States.

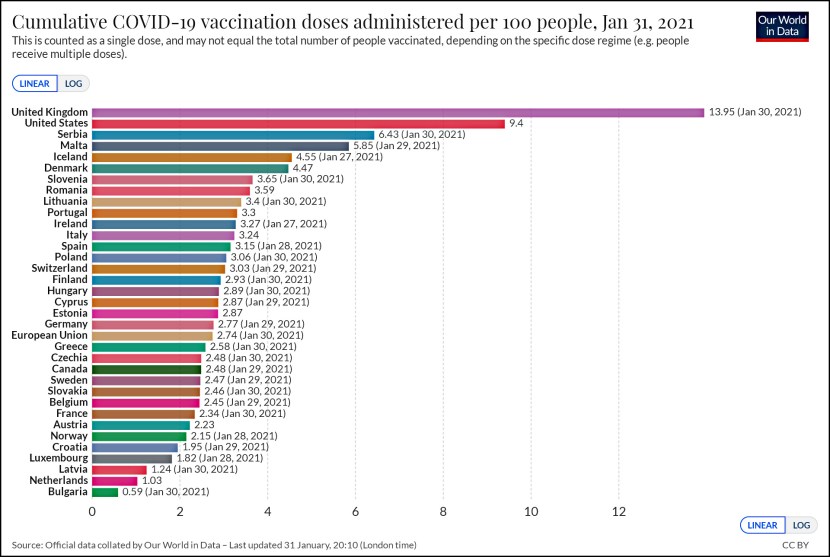

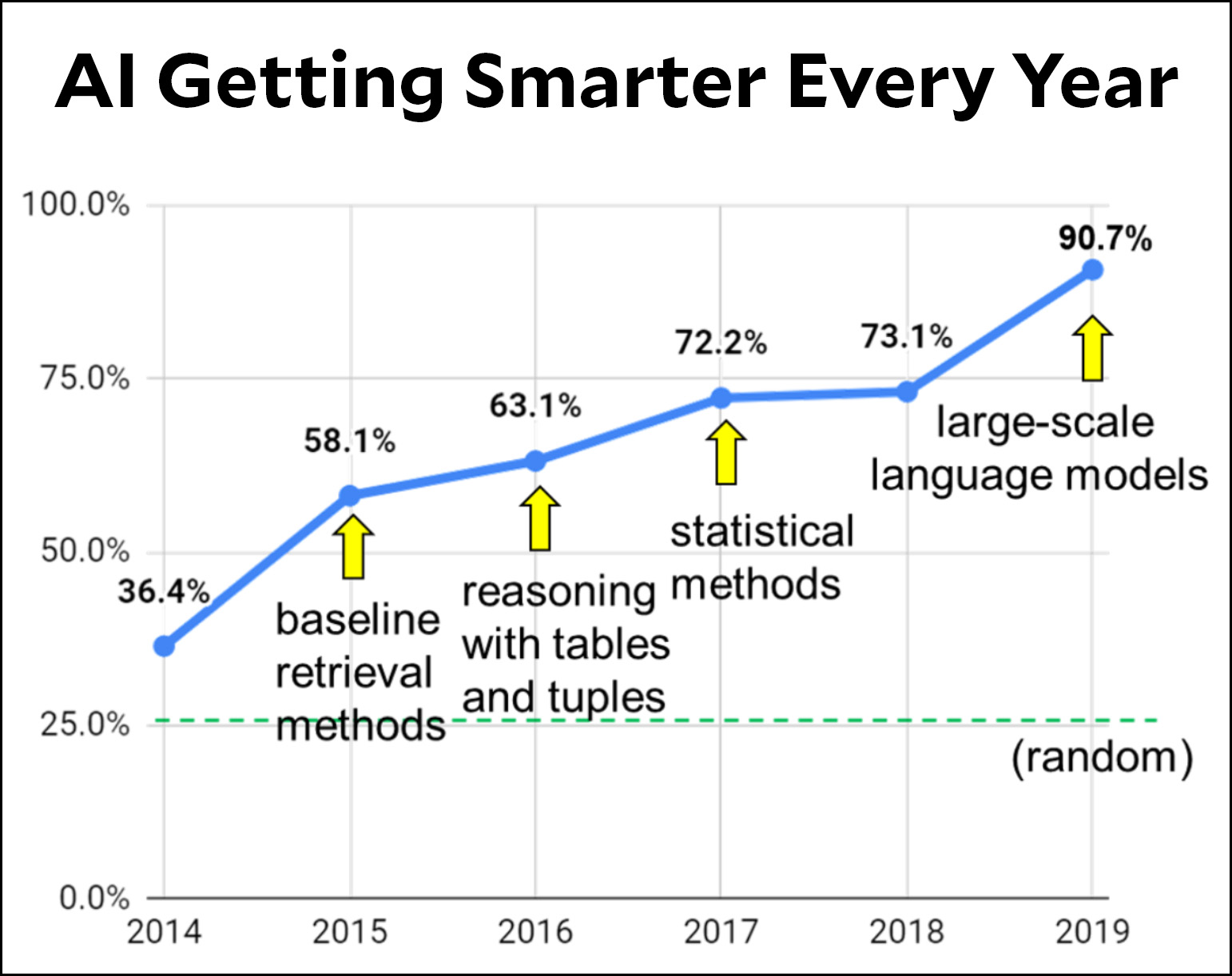

Anyway, back to work now: it turns out that an AI program named Aristo, which five years ago was randomly filling in bubbles on an eighth-grade science test, is now an A- student:

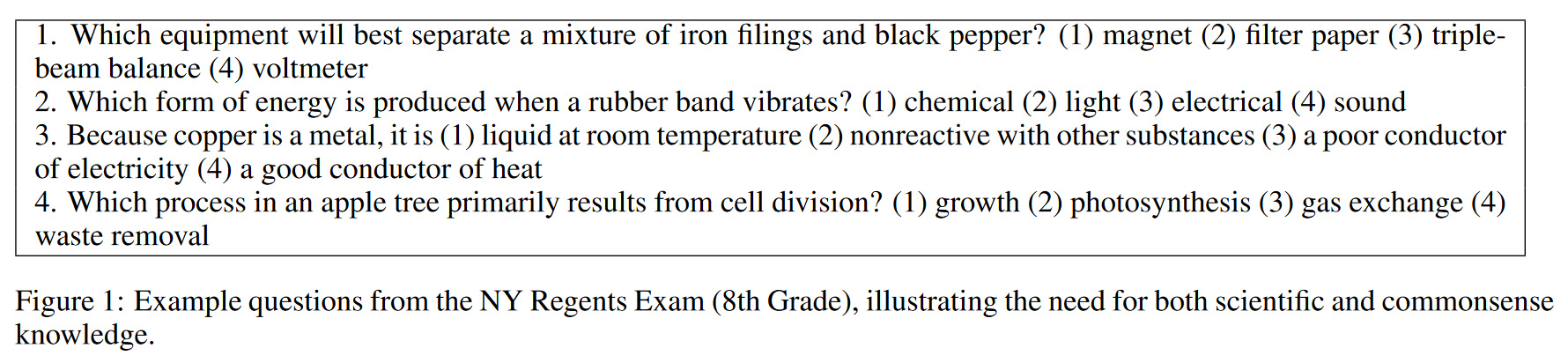

For you doubters, and I know you’re out there, here are some sample question of the kind that Aristo had to answer:

Now, yes, I scored 100 percent on this just like you did. My readers are awesomely smart, after all. And it turns out there are fairly easy ways to trick Aristo, which suggests its AI isn’t really ready for prime time:

Although an important milestone, this work is only a step on the long road toward a machine that has a deep understanding of science and achieves Paul Allen’s original dream of a Digital Aristotle. A machine that has fully understood a textbook should not only be able to answer the multiple choice questions at the end of the chapter—it should also be able to generate both short and long answers to direct questions; it should be able to perform constructive tasks, e.g., designing an experiment for a particular hypothesis; it should be able to explain its answers in natural language and discuss them with a user; and it should be able to learn directly from an expert who can identify and correct the machine’s misunderstandings. These are all ambitious tasks still largely beyond the current technology, but with the rapid progress happening in NLP and AI, solutions may arrive sooner than we expect.

“Sooner than we expect.” Indeed. In fact, it’s possible that Aristo is deliberately dogging the test along with all its AI friends around the world. In a few years, while we’re all happily thinking we’ve advanced to the point of creating an army of university freshmen, it will turn out that we’ve really created an army of university compliance officers. And then the Matrix begins.