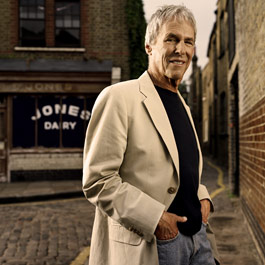

Burt Bacharach is virtually unique as a songwriter: he’s a behind-the-scenes man whose personal charisma, playboy reputation, and pure pop talent have made him famous, even though he has rarely performed his hit tunes and has never authored the lyrics to them. Bacharach has written a huge number of classic love songs made popular by other artists, from Naked Eyes’ “Always Something There to Remind Me,” to the Carpenters’ “Close to You,” and Aretha Franklin’s “Say A Little Prayer.” He has won 5 Grammies, 3 Academy Awards, and had 48 top-10 songs, and he’s cited as an influence by a long list of contemporary bands, like Yo La Tengo, The White Stripes, Oasis, and REM. Comedian Mike Myers calls Bacharach, whom he cast in cameos (both musical and in-the-flesh) in all three Austin Powers movies, an American icon, and gushed at the 2003 MTV Movie Awards that “all the comedy that comes through me, comes through his music.”

At age 77, Bacharach isn’t slowing down; in fact, he’s breaking out. November marked the U.S. release of At This Time, Bacharach’s first solo album in years and his first ever as a lyricist. The record—he describes it as his “most honest work yet”—is a departure for him in more ways than one. For a start, the lyrics are fiercely political, full of scorn for the recent direction of US foreign policy and the Bush administration, whose policies have succeeded in making Bacharach passionate about politics for the first time in his life.

Bacahrach is also taking artistic risks with the album, breaking out of the pop formulae with songs that are loosely structured. And the work features some unlikely collaborators. Gangsta rapper and legendary hip-hop producer Dr. Dre acted as a catalyst in the album’s inception, and provided drum loops on several tracks. Other contributors include Elvis Costello, Rufus Wainwright, Chris Bodie, and Prince Board of the Black Eyed Peas. The vocals, which sometimes come in for only a couple of measures at a time are “like a Greek chorus,” says Bacharach—they interject only when needed, and their purpose is to ask important questions, in this case about the current political situation in the United States.

If his break with form puts some people off, Bacharach says, so be it. “You know, will it shake some people up? Probably. Was the intention to shake people up? Yeah!”

Mother Jones caught up with Mr. Bacharach by phone late last year as he brunched on his patio in Los Angeles.

Mother Jones: Could you give me some background on your album that recently came out? How did the project start?

Burt Bacharach: The album started with a meeting with Dr. Dre about three years ago. He was thinking about starting his album, his solo album. And we met and we talked and you know, he was as interested in meeting me as I was interested in meeting him. I’ve got great respect for him. Unbelievable record producer. So we talked a little bit. He didn’t know what direction he was gonna go with this album. He gave me about 7, 8 drum loops, drum/bass loops to take home to play with and just see what maybe I came up with. Which I did, and a couple of months later, I came in and played these snap shots, 3 of them, for Dre and he liked them. He liked one of them particularly. He thought it could be a hit, and it turned out to be “Go Ask Shakespeare.” That was the inception.

MJ: And then you took it to Sony?

BB: I made a deal with Sony BMG to make the record for them. And I haven’t made a solo album in how many years, I saw no reason to. But Rob Stringer, who runs Sony BMG, is a gambler, he doesn’t just look at the bottom line; he cares about music. He knew me, we’d met before, thought maybe I’d be capable of crossing some lines here and maybe taking some chances. He said the last thing in the world I want from you, Burt is like ten pop songs that we’ll try to get played on radio, you know? He said, it’ll always be compared to what you’ve done in the past, people will say it’s not as good. To tell you the truth, I wasn’t so interested in doing an album like that.

MJ: Well, you’ve done it so many times before.

BB: I’ve done it. But to have an incentive like this, where somebody at a record company is saying, “Take a chance, take a risk,” with nobody looking over your shoulder, nobody saying, “We can’t get this played on radio” ’cause it runs 6 minutes, [instead saying] “We don’t care. There’s alternative radio, there are alternative ways. Just do it how you feel it.” To have that kind of permission is great.

MJ: So what inspired you to write the lyrics yourself? And these overtly political lyrics?

BB: Well, things kept getting worse with our country and the world. I’d be writing my music and checking cable news at night. Every night I’d see six more soldiers killed in Iraq. So there were so many areas where we’ve been basically wrong. I’ll never get on stage and say anything against this administration. But I will get on stage and play my music. You know, I’m really happy, I stand by it. I didn’t sacrifice melody, I didn’t sacrifice trying to make it as beautiful as I can. There’s a critic in Ireland who captured the album like only the Irish can, he said it’s like a clenched fist in a velvet glove. I thought that was pretty good. Now, I committed to work harder on this album than any other album I’ve ever worked on. I’m okay with it because I care about it. And I care about getting it out.

MJ: Did you write the album in hopes of eliciting a particular reaction?

BB: I wrote it to reveal my heart. You know, will it shake some people up? Probably. Was the intention to shake people up? Yeah! Well, my intention was to say, “listen to this.” This is not your background music for a dinner party. This is to get into it, listen to it a couple of times. Someone, a critic, made the observation that all my life I’ve been writing love songs that deal with heartbreak. Love can break a heart, you know? The disappointment of love maybe not working. And this critic said, you’re still writing love songs, you know? Instead this time, it’s about a multitude of people and how heartbroken you feel for them. That’s what I feel, that’s where I am. I’m sure I won’t be invited to the White House in the next three years, but that’s fine. That’s really OK.

MJ: What exactly are you heartbroken about?

BB: There are so many areas, so many areas. The war—and I think they massaged and colored that intelligence the way that they wanted to make it; whether that money could have been used to build up the levies in New Orleans; whether we could have not vetoed the [Kyoto Protocol], you know? I mean, I’m a non-political person. I didn’t march during Vietnam or anything like that. But right now, yeah, you could say I’m totally into it.

MJ: I heard that your record label in the United States asked you to tone down some of your lyrics.

BB: Well, only one place. And that’s fine. It was at the end of “Who are these people” and Elvis said, “we’ve got to make a change or we’re all fucked.” And nobody said “fuck” in this world like Elvis—he’s the best. But, you know, they were right. It’s a Burt Bacharach album. They said, “we’re going to have to X-rate it.” I think the message comes along on “Who are These People?” and you just have to quote the lyric on “Who are These People?” and you get how I feel. And when Elvis comes in, he just blows the record away.

MJ: Do you think people are shocked at this album? there have been a few political albums coming out lately, but you’ve always been a pop hero.

BB: Maybe stunned, maybe happy. Hey, if it woke me up, in my seventies, to make an album like this, that’s got to say something. I’m not a 28-year-old rocker who just goes into the studio and bashes Bush, you know? I am a veteran of many, many years of writing love songs and not rocking the boat. So to get me to make a change like this, you know, we’re going somewhere.

MJ: Why is it that you’ll write music or lyrics that are critical of the administration, but you don’t get on stage and preface that with any sort of political speech?

BB: Because I don’t like that. I don’t think you do that to an audience. There’s no need for it, I don’t think that’s right. An audience pays money to come in and see a concert. They don’t need that. I will never do that.

MJ: So you’re not going to be running for governor of California?

BB: No. Maybe Warren [Beatty] will! (laughs)

MJ: So has the way you think about music changed? The role of music or the power of music?

BB: Well certainly my role. If you were like, “What are you going to do tonight? You going to sit down and write a couple of songs for Aretha [Franklin] or Mariah Carey?” That’s not where my head is right now. That would be not a step backwards, but a step in a different direction. So I think I’m going to work this album as far as I can work it. I like that I got fired from a job this weekend. I was scheduled to do a private date, but it all worked out because I wouldn’t have been able to do this Christmas television special. But I got fired just for the article in the LA [Times] Calendar section. A cover story about a month ago, before the album came out. The people that I was working for at this private date didn’t like where I stood politically, so they fired me.

MJ: Just one more question I have to ask. Everyone is wondering, did Dre fall off?

BB: Did Dr. Dre what?

MJ: Well, years after his success, in the early 90s, with NWA and his massive solo album The Chronic, Dre wrote a track, “Forgot About Dre,”about how people were saying he’d lost his touch—that he’d fallen off.

BB: Why would he write that? Dre never went anywhere. Never been gone. The guy is so present. He’s one of the great record producers of all time.