James Lewis died at night, after a football game. The Miami Northwestern Senior High Bulls had played the Booker T. Washington Tornadoes. In the parking lot outside Traz Powell Stadium, Lewis stood among a small crowd. A bullet fired from a pistol entered his body in what friends say was an assassination. Lewis was popular in school. He owned two cars. He made other people jealous, his family says. At age 17 his life looked good, too good for Liberty City, so he had to go.

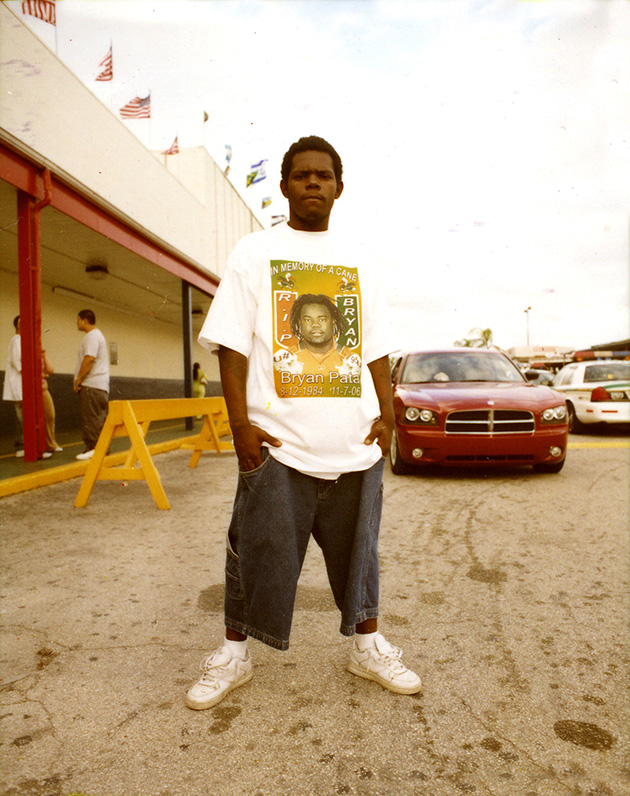

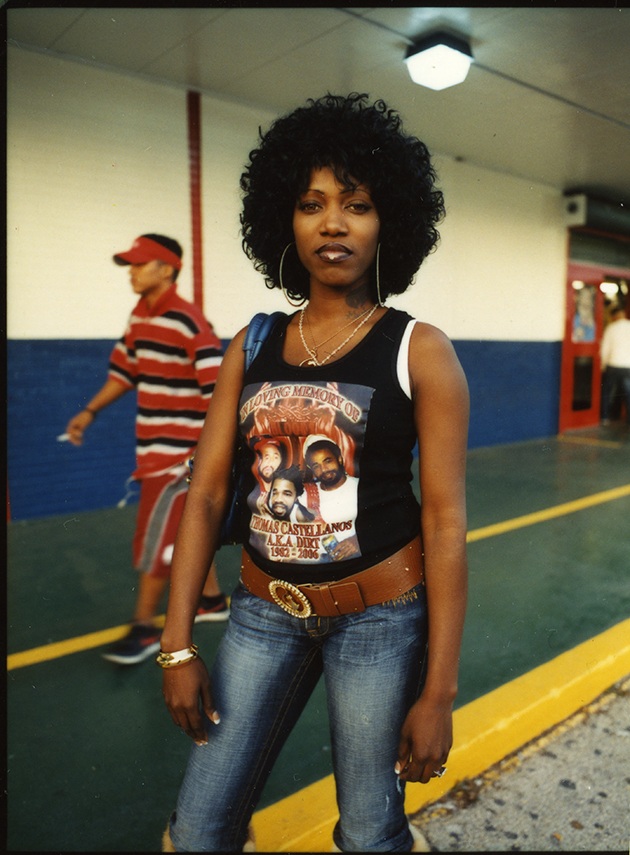

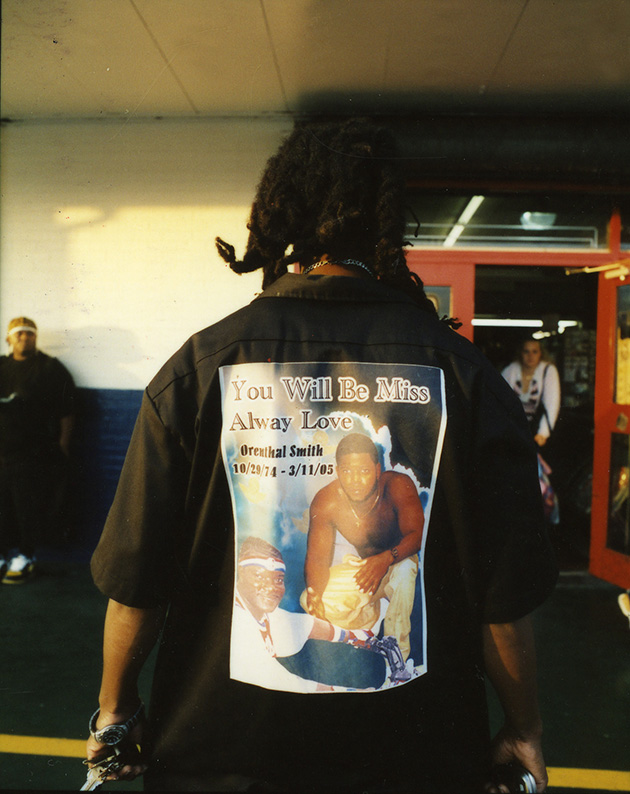

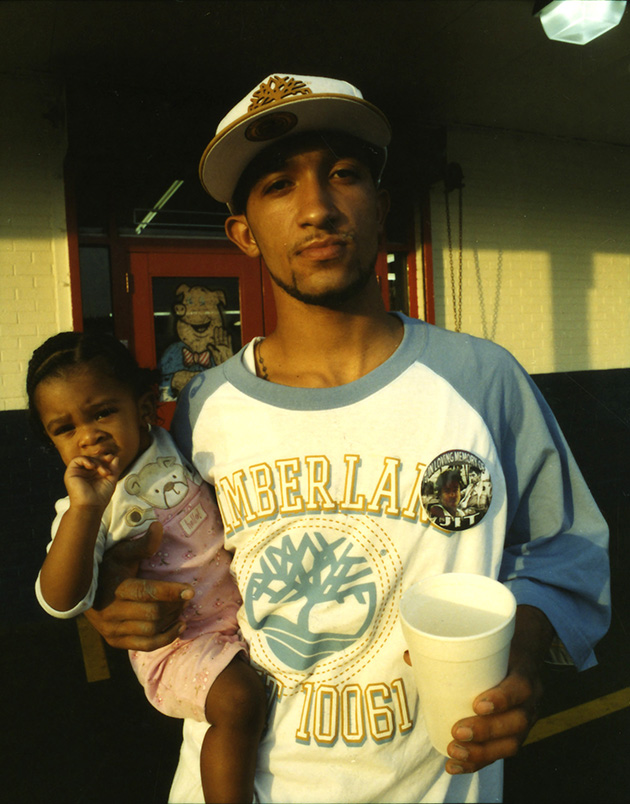

The shooting occurred around midnight. When Studio X opened the next day at 10:30 a.m., Lewis’ girlfriend was waiting. In her fingers she clutched a photo of her boyfriend, also known as 3-J. She wanted to put him on a T-shirt. Studio X is a booth at Flea Market usa, located on Northwest 79th Street, in Liberty City, the heart of black Miami. Owner Chino Mizrachi has worked the flea market for the past 17 years. Some simply refer to his booth by what they go there for, “In Loving Memory Of” T-shirts. Mizrachi sells 500 In Loving Memory Of T-shirts a week, on average. More when someone popular dies, or if the week was particularly violent. He occasionally makes shirts memorializing, say, a grandmother who died of old age. But most shirts feature teenage boys, shot for various reasons, most often for no good reason at all.

Death is a stable business in Liberty City. The murder rate across Miami-Dade County increased by nearly 40 percent last year, and more than twice as many kids under 18 were killed in 2006 than in the previous year. In November, a Miami-Dade Police Department gun buyback event netted more than 1,100 revolvers, shotguns, rifles, and semiautomatic firearms, in four hours. “It’s just deteriorating,” Mizrachi explains. “It’s just going from bad to worse. I don’t know where it’s going to stop. It used to be one guy a week and two guys a week, but nowadays you can find in one night, like, three or four guys can get killed and nobody cares.”

The dead live on in two-inch-thick plastic binders shelved atop the main counter of Mizrachi’s booth. The binders, which he refers to as “the most popular library in the city,” contain pictures of almost every person he has memorialized. The images are filed chronologically, by date of death. Customers flip through the binders while they wait for their new shirts to be pressed, passing time as if walking through a cemetery appraising gravestones. There’s a young boy in cap and gown. Another picture is labeled “Baby.” There’s a guy named Kick Daddy and an older woman posing with a parasol. A young man squats with a pistol in his hand. His picture is labeled, at the customer’s request, “Heaven for a G.” The newest arrivals wait in plastic bags, photos to be filed in the binders later.

“In Memory Of a Hustler, Luciano Shuler a.k.a. Lucy.”

“Damn, I miss my DAWG!!!” the words arcing slightly over a camouflage background.

“In Loving Memory Of Stank.”

The dead also live on the back wall of the booth, on what Mizrachi’s friend Judas, a tattoo artist, calls “The Spooky Wall.” Dozens of pictures hang in a gallery. In a typical photo, a man in sunglasses squats, head cocked, holding guns in both hands. “We call that the prison pose,” Mizrachi says. “That’s the classic pose. Holding, like, a submachine gun or something like that. Then he’s squatting down. There’s a brick wall behind him. That’s the pose. He’s got a mean look on his face; he’s a real big shot.”

Throughout the booth hang samples of other products Mizrachi offers, such as buttons with people’s faces on them. And flags, with images on each side, that can be attached to cars like sports pennants. One of the newest offerings is “dog tags,” which cost $30 for a small tag, and up to $70 for larger ones encircled in fake gemstones. Mizrachi is always pushing the dog tags. “The shirts still sell more, but dog tags make more money,” explains Leonard Brown, one of Mizrachi’s three employees. Brown is 19, a kid from the neighborhood. His father was killed when “he was in the wrong place at the wrong time.” He’s been working at the booth after school and on weekends for seven years, mostly designing T-shirts. “To me a shirt is like love, you know what I’m saying? It symbolizes love,” he says. “If you love that person, you’re going to go out and get a shirt and just walk around in the streets to show people, I knew him, he was my homeboy and I got love for him and I miss him.”

Customers can order pre-designed shirts, or they can create a design from scratch, using a picture they bring or a digital file. On a form they write the name of the deceased, along with the birth date and date of death, sometimes described on the shirt as “sunrise” and “sunset.” Mizrachi or one of his employees scans the picture, then Photoshops it into a number of templates:

“In Loving Memory Of” atop palm trees or a beach scene or clouds and angels.

“In Thugin Memory Of” atop a picture of the Miami skyline and a pair of Cadillacs.

“In Loving Memory Of a Soldier” over camouflage and crossed guns.

“In Loving Memory Of a Player” over a roulette wheel and a pair of dice.

3-J’s girlfriend opted for white clouds in a blue sky. In the picture 3-J wears a baby-blue Atlanta Braves cap with a gold authenticity hologram stuck to its brim. He crouches in the prison pose. In Loving Memory OfJames LewisA.K.A. 3-J Sunrise, sunset. The whole process takes about five minutes. With a popular kid like 3-J, it’s common for customers to have to wait in line for two hours or more. They stand with friends or with family members or with people who just want a T-shirt to fit in with the fashion of the neighborhood. “They know the best place to be together to talk about the guy is the T-shirt place,” Mizrachi says. “They have no place else right after. Two, three days after, there’s the wake, but when it happens, it’s fresh, they all come to me here.”

Chess champion Sherdavia Jenkins, 9, was shot to death in front of her house last July. In August, aspiring fashion designer Otissha Burnett, 17, was killed by one of more than 20 bullets fired at a block party. Last May 21 it was 17-year-old Jeffrey Johnson who was shot and killed. He’d been a student in the law magnet program at Carol City Senior High. He carried a 4.9 grade point average, interned at the Miami office of Rep. Kendrick Meek (D-Fla.), and won a scholarship to St. Thomas University, where he planned to study law. As a reward for his good grades, his father had bought him a burnt-orange Chevrolet Monte Carlo with wide tires, gleaming rims, and doors that opened up like wings. The car played well in Liberty City. At a block party just before graduation, Johnson parked nose-to-nose with a candy-apple red Pontiac Grand Prix. With a DJ egging them on, the two owners vied for approval. The Monte Carlo got applause for its interior, but the crowd preferred the chassis of the Grand Prix. “While they were having this battle of ‘My car is better than your car,’ the victim pulled on his graduation cap,” Miami Police spokesman Delrish Moss later told the Miami Herald. This was perceived as an insult, a sign that Johnson believed his future trumped any mere vehicle. The insulted driver punched Johnson. Soon dozens of shots rang out. A bullet struck one boy in the right thigh; another boy was shot in the foot. Johnson was struck in the torso. The police found his mortarboard—white cloth stretched over a sturdy square of cardboard–next to his body.

Johnson was the third Carol City High kid to be gunned down last school year. One student died in a robbery attempt; another went into a store to buy milk for her baby and was shot on the way out. Police say at least 60 people witnessed that shooting, but no one stepped forward to identify her killer. Rep. Meek called Johnson’s death “a terrible tragedy for our community.” On a memorial poster to Johnson hung at his high school, someone scrawled, “We can’t keep losing our brothers like this.”

The morning after Johnson died, Mizrachi arrived at his booth, unrolled the metal door, turned on the cash register, and fired up the copier, computers, and steam presses. “When I heard about that guy on the news, I called my guys and told them to be ready,” he says. Outside there were people waiting, eager to put Jeffrey Johnson’s face on a T-shirt.