Ciudad Juarez, the death-kissed industrial town that borders El Paso, Texas, is never far from the drug mafia’s crosshairs. Casualty No. 1 of Mexico’s drug war, this is a city whose mafia forced its police chief to resign by killing a police officer every 48 hours until he did.

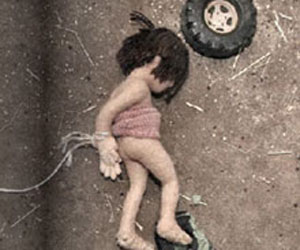

Most of the drug war’s soldiers are young men, but I Live Here, a graphically illustrated “paper documentary,” turns its attention to the city’s beleaguered young women. Hundreds of kidnapped girls, many of them factory workers, have been brutally and mysteriously murdered since 1993. Comic artist Phoebe Gloeckner uses cloth, yarn, and what appear to be scraps from a Juárez factory floor to suffuse her graphic novella with eerie immediacy. Other pages look like a grade-school diorama project gone horribly wrong: Gruesome murder scenes are recreated with felt dolls, victim headshots, and police report excerpts.

This is just one of four volumes in I Live Here, a Mia Kirshner-powered project that tells the stories of victims and survivors in four global hotspots: refugees in Chechnya, child soldiers and prostitutes in Burma, families of the disappeared in Mexico, and AIDS victims in Malawi. Kirshner and her collaborators, including award-winning author J.B. MacKinnon, ex-Adbusters staffers Michael Simons and Paul Shoebridge, and renowned comic artists Joe Sacco and Phoebe Gloeckner, depict these crises through short stories, poetry, photography, and collage, incorporating first-person accounts and images from their travels.

The effect of so many cooks in the kitchen, let alone so many different menus and ingredients, can be jarring. The reader is never able to settle comfortably into the book; perhaps we are meant to stay suspended in a state of unease while viewing such raw, wrenching portrayals of human suffering.

Unfortunately, the artists sometimes evoke an off-pitch homage to scrapbook chic that induces twinges of first-world embarrassment. The writing, too, suffers from switchback point-of-view changes and can come off as tin-eared and self-conscious.

Still, there are poignant gems throughout the book that bring you beyond the false notes to connect with the human beings behind the stories. The highlights of the four volumes are the graphic novellas contained in each one.

The Chechnya piece is classic Joe Sacco: true-to-life comic-strip journalism based on firsthand reporting in the Ingushetia refugee camps. In the Burma volume, bleak black-and-white paintings by Kamel Khélif tell a frame-by-frame story of Mi-Su, a sex worker just over the border in Mae Sot, Thailand. Many images are based on Mi-Su’s photographs; the story is told through her answers to a Vancouver sex worker’s questions.

The final volume, on Malawi, features a singsong children’s story by J.B. MacKinnon, beautifully illustrated by Julie Morstad, which conveys a morbid, childlike acceptance of death as a matter of fact in a village wiped out by the “wasting disease.”

Kirshner, the granddaughter of Holocaust survivors and daughter of refugees, attempts to weave her family history journals throughout the book. Though the effect can be confusing, it’s clear Kirshner is trying to draw parallels between her Western life and the vastly different lives of these survivors.

The book ultimately poses an empathetic question to readers: It challenges us not only to imagine ourselves in their shoes, but to imagine these resilient survivors in ours. What would the sex worker, child soldier, or AIDS victim be like if they grew up and went to school with us? Would they still be so different, or outcast, or faceless to the world?