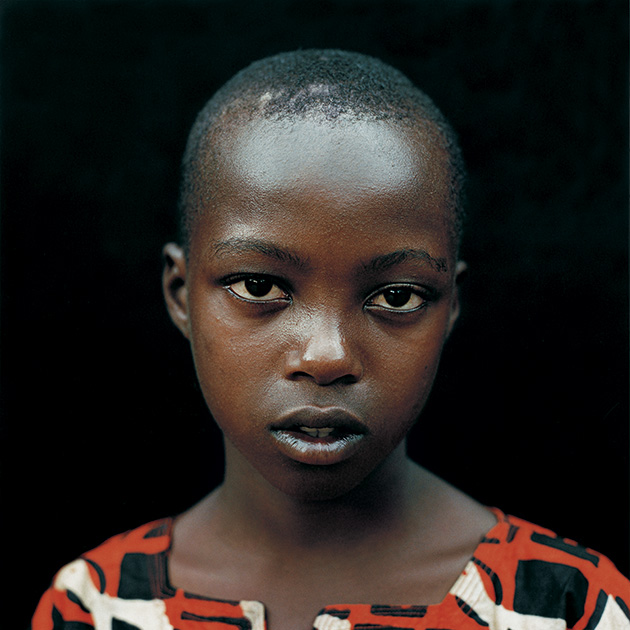

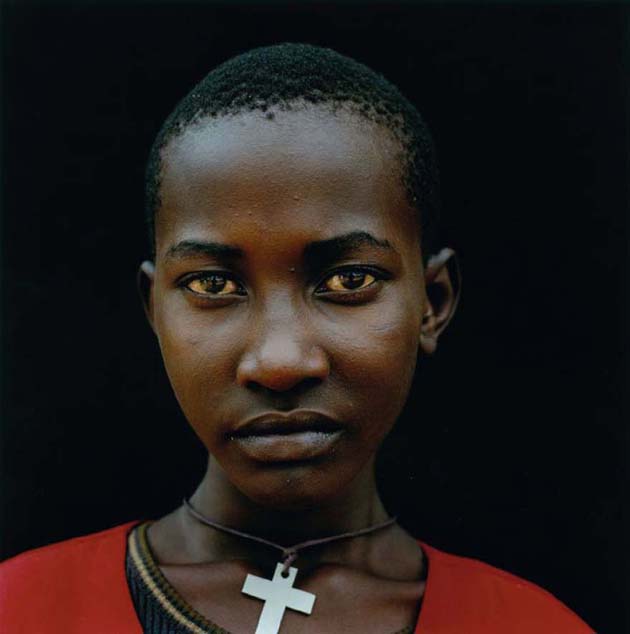

In 2006, photographer Jonathan Torgovnik began work on what became a three-year project photographing and interviewing Rwandan women who had children as the result of being raped during the genocide. Torgovnik won the 2007 National Portrait Gallery’s Photographic Portrait Prize for an image from this work. The culmination of his project is an exhibition and book, Intended Consequences: Rwandan Children Born of Rape, published by the Aperture Foundation. Inspired by the people he met on this project, Torgovnik co-founded Foundation Rwanda, established to improve the lives of Rwandan children born of rape.

The militias came in the evening and locked us in a house. Then they said they were going to rape us, but they used the word "marry." They said they were going to marry us until we stopped breathing. Every morning they hit us 10 times. After hitting us, we got a different man. Eventually my sister said it was too much, that we needed to commit suicide. There was a river close by that my sister heard people talking about. We went to look for it so we could throw ourselves into the river and die instead of living with torture. But when we got to the river, there were many dead bodies floating in it, and we feared going there.

I must be honest with you; I never loved this child. When I remember what his father did to me, I used to feel that the only revenge would be to kill his son. But I never did that. I forced myself to like him, but he is unlikable. The boy is too stubborn and bad. It’s not because he knows that I don’t love him; it is that blood in him. —Josette

We started sensing trouble when soldiers came and began rounding people up. But they didn’t say anything until around noon when they told all the men to go to one side and all the women to go to the other side. When the men went to the other side, they started shooting them.

A local leader called a meeting, saying, “People should go back to where they came from…girls and women can go back to their places of origin.” I went to a house to ask for water. They sent me away. As I was reaching the end of the road, I met the owner of the home. He looked at me with a lot of bitterness and cut me in the face with his machete. I ran, but was feeling weak. I reached a place I thought would protect me for the day because I didn’t want to walk in the daytime. You could hear people being killed with machetes, being hit with clubs, or being speared.

I went to a Catholic Church. There was a group of militias there, but one of them who knew me advised me not to hide there because I had a wound that would easily identify me as Tutsi. He told me to hide in the houses near a place called Rango. He sent two young men to kill me there. They hit me with machetes and clubs, saying I shouldn’t die in the house because my blood would cause bad omens. They took me to the forest and raped me there.

After they raped me, they called to another two boys; one of them said, “This woman is sweet, you also need to enjoy her.” After that, they said, “This Tutsi woman is not getting satisfied. Let’s get a corn stem and sharpen it to the shape of a penis; that will satisfy her.” So they went to cut that piece and they put my legs apart and then they started pounding that stem of corn into my private parts. After that night, I couldn’t walk.

When the leader of the militia saw me, he said, “These people must be killed because we killed all the others. If we leave them, they are going to report us when things don’t work out. Or they will be a bad omen.” And one of them asked, “Now, how do we kill 30 people? There are too many.” Another man offered to take us to his land where he had already dug a grave. He said, “Let us take them and kill them there. And then when they rot, they will be fertilizer for my farm. I will plant banana plantations afterward, and they’ll be fertile.” —Anne-Marie

When they attacked my husband’s house I was two months pregnant, carrying a little girl. The head of the militias was ruthless and put a spear in my leg to force my legs apart. I was raped every night, and during the day, they locked me in. I gave birth to my daughter, and shortly afterward, I became pregnant again.

I love my first daughter more because I gave birth to her as a result of love. The second girl is a result of unwanted circumstance. I never loved her father. My love is divided, but slowly, I am beginning to appreciate that the younger daughter is innocent. Before, when she was a baby, I left her crying. I fed the older one more than the younger one, until people in the neighborhood reminded me that was not the proper thing to do. I love her only now that I am beginning to appreciate that she is my daughter, too. We have not revealed everything to the girl—she thinks she is like her sister. —Valentine

My message to my children is: Don’t look at whether one is Hutu or one is Tutsi.

Before the genocide, I had a family, I had parents, I had relatives, I had brothers and sisters; we lived a happy life until the genocide came and destroyed it. Everybody was killed, apart from me.

On April 6, the president was killed, and Tutsis around our village were targeted by Hutu militias that were very organized, like they had prepared this for many years. My family fled to the nearby church. A priest told me I should hide in the head priest’s house. When I entered the house, he called his friend and said this was an opportunity for them to “enjoy a Tutsi girl.” And so they raped me, both of them raped me three times each in the house of the chief priest. He called in other militias, and they almost killed me. Outside the parish, my upper teeth were removed with clubs. They had dug holes in the forest. There, they hit me with clubs and machetes and threw me among the dead bodies. They thought I was dead. I don’t know how I survived, but in the night, I managed to walk slowly through the dead bodies and then quietly through the bushes. But I was discovered along the way by many militiamen, and they all raped me.

Each time I was “saved” by someone, he would rape me and then lead me to another bush where I would be raped again. I was raped by many men. The final man who raped me kept me captive in his house for several days. He would go out to kill during the day and come back at night to do whatever he wanted to do to me. Fortunately, one day when he went out to kill, he never came back.

When I found out I was pregnant, I thought that I would kill the child as soon as it was born. But when she arrived, she looked like my family, and I realized she was part of me. Now, I love my daughter so much; actually our relationship is more like sisters. I got married to a man and told him the whole truth about my daughter. I thought he would protect me, but four years down the road, he seemed to change his opinion about her. We are separated now. I think I would rather be alone and have my daughter with me. If I had the means, I would send her to secondary school because that is the only inheritance she will have.

I don’t encourage my children to advance ethnic ideologies. My message to my children is: Don’t look at whether one is Hutu or one is Tutsi. That’s not what is important. —Claire

Be sure to also visit MediaStorm’s multimedia presentation of Intended Consquences.