Photo: Ali Pflaum

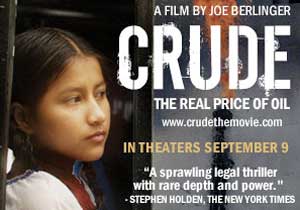

Darkness is never far from the surface of Joe Berlinger’s films. In his latest documentary, Crude, it takes the form of oil—billions of gallons of the stuff that have saturated a once pristine swath of the Amazon rainforest and fueled a 16-year legal battle between indigenous Ecuadorians and the oil giants Texaco and Chevron. The environmental theme is a departure for the 47-year-old director, who’s best known for in-depth looks at misfits, murder, and heavy metal. He made his name in 1992 with Brother’s Keeper (codirected with longtime collaborator Bruce Sinofsky), the tale of an elderly eccentric who may or may not have killed his brother. That was followed in 1996 by Paradise Lost, a harrowing film that turned the case of the West Memphis Three—a trio of Arkansas teens convicted of murdering three eight-year-old boys based on flimsy evidence of satanism—into a cause célèbre. That film and its sequel eventually led Berlinger to make Metallica: Some Kind of Monster, the 2004 rockumentary about a different kind of headbanging—group therapy for rock stars. Berlinger spoke with Mother Jones from his office in New York. For an extended version of this interview, go to motherjones.com/joe-berlinger.

Mother Jones: What was more arduous: a couple of years in the rainforest, two years in the studio with Metallica, or following the West Memphis Three for the past 15 years?

Joe Berlinger: I would definitely say that this film was really the hardest thing I’ve ever been involved in. We were sometimes shooting in 120-degree heat. The area has just been devastated by oil production and pollution. You end up with a splitting headache because the fumes were so intense. I was advised by my doctor to take Malarone, which is an anti-malarial. On the third or fourth day I almost pulled my Martin Sheen Apocalypse Now moment because I felt like I was going psychotic. The other hard part was just the emotional toll. You’re dealing with people—young kids, 18-year-olds who are dying of cancer, people who just feel hopeless and devastated because there’s literally no clean water. So it was really not an easy film to make, on every level. But it’s probably the most fulfilling thing I’ve ever been involved in.

MJ: So how did you learn about this story?

JB: Steven Donziger, the American lawyer in the film. At first I was dubious. I said to him, “I am not an agitprop filmmaker. I’m a filmmaker who is known for these ambiguous portraits that tell multiple sides of the story without really telling the audience what to think. But knowing that, if you still want to take me down there, let’s check it out.” Then I went out to Lago Agrio, Ecuador, which literally means “sour lake.” It’s named after Sour Lake, Texas, which is the birthplace of Texaco. I felt like the universe was tapping me on the shoulder saying, “You’re the guy who has to tell this story because nobody else is.”

MJ: You give Chevron a lot of time in the movie, which really complicates the question of who’s legally to blame.

JB: My attitude is, I am not a lawyer; I am not a doctor; I am not a scientist. I am a filmmaker and I want to present what each side is saying and let the viewer come to their own conclusion. Chevron has wrapped itself in some pretty good arguments that make you scratch your head. The moral responsibility is certainly at its door. I leave it to other people to figure out whether there’s legal responsibility.

MJ: What would you like to see come out of this film?

JB: I hope that the film sends the message out that you should be very aware of where your products come from and how companies act in your name. On a more direct level, I would love people to donate to the Ecuador Water Project [a UNICEF program founded by Trudie Styler, Sting’s wife]. The only tangible benefit that these people have received from all of this attention to this case is the fresh drinking water. It is a sad comment on our society that it takes the wife of a famous rock star to come winging into the Amazon to pressure UNICEF to get involved.

MJ: Have there been any updates to the case since you’ve finished the film?

JB: There’s a new judge, who is going to render a decision by the end of the year. Chevron has vowed to fight any verdict that comes out, and it’s promised a “lifetime of litigation.” So I think it’s going to go on forever. Look at what’s going on in Paradise Lost. Poor Damien Echols [of the West Memphis Three] is spending his 16th year in a supermax prison.

MJ: Are you working on another update to Paradise Lost?

JB: In theory. But there hasn’t been a lot to film because we’re not allowed in the courtroom—we were thrown out a long time ago. We’re committed to telling the end of the story. Paradise Lost has created this huge movement and a lot of celebrities from Eddie Vedder to Johnny Depp have gotten involved in the case. I think because of that support, the state of Arkansas will never actually take the step of executing Damien.

MJ: Do you have any theories on who is the real murderer?

JB: I’d rather not get into my theories. My personal belief is that the kids are definitely innocent. There is just an abundance of reasonable doubt.

MJ: Damien Echols says that Metallica’s “Welcome Home (Sanitarium)” is his favorite song. Did that make the connection with the band that led to Some Kind of Monster?

JB: One of the great ironies of my career is that people imagine me as some sort of hardcore metal guy because of the Metallica film. But the reason we met Metallica was that their lyrics were introduced into the trial. It led to a relationship, which led to the film.

MJ: Did you get some benefit from the group therapy Metallica went through?

JB: I actually did. After Paradise Lost 2 I went and did the disaster of my career, the sequel to the Blair Witch Project. It was not a small disaster; it was on a worldwide belly-flop level. So I called [Metallica drummer] Lars Ulrich up and said, “You wanna make that film now?” I went out to San Francisco, started shooting, and within a week, the band was falling apart. Lars looked at me and said, “You know, I’m not sure, they’re bringing in this performance enhancement coach.” I said, “Lars, that‘s the film.” I felt so grateful to be sitting there and listening to this because I felt like, “Look, here are incredibly successful people who are going through their own creative and existential crisis, just like me.” That’s what I love about the film: It explodes your stereotype of them—they’re not just a bunch of lugheads banging on the guitar.